Array Collective, a group of activist artists from Belfast, has won the Turner Prize 2021, it was announced in a ceremony in Coventry this evening.

They are the first artists from Northern Ireland to win the Turner Prize since its inception in 1984. The prestigious award is named after the radical British painter JMW Turner.

The collective will receive £25,000 in prize money, while a further £10,000 will be awarded to four other shortlisted artist collectives. This is the first edition of The Turner Prize to only feature activist artistic groups—no single artist is on show here.

Works by each of the collectives are now on show at the Herbert Art Gallery in Coventry, the UK’s City of Culture 2021, until 12 January 2022. The jury consisted of: Aaron Cezar, the director of the Delfina Foundation, Kim McAleese, the programme director of Grand Union, the actor and collector Russell Tovey and Zoe Whitley, the director of the Chisenhale Gallery. The jury is chaired by Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain.

Array Collective, International Women’s Day 2019 © Alessia Cargnelli, courtesy The Turner Prize

The ceremony in which the winner was announced took place at Coventry Cathedral, a ruined shell of a Gothic church, a charred cross at its centre. Just over 81 years ago, on Thursday 14 November 1940, the German army enacted Operation Moonlight Sonata, an all-night blitz of Coventry recorded as one of the most devastating bombing raids of the Second World War.

In an opening statement, Hammad Nasar, the exhibition’s lead curator, celebrated the works on show for their ability to act as “exercises in the real world.”

“The artists on show are not content to notice things in the world and to point them out to the rest of us through works that live inside museums and galleries,” Nasar said. “They are instead engaged in constructing pocket utopias—exercises in the real world that deploy the artistic imagination to propose new, more equal, more hopeful futures.”

Array Collective have been working together since 2016, motivated by “the growing anger around human rights issues” in Northern Ireland and beyond. The group was founded “to reclaim and review the dominant ideas about religio-ethnic identity in Northern Ireland,” they say.

The jury awarded Array Collective for the way they “were able to translate their activism and values into the gallery environment, creating a welcoming, immersive and surprising exhibition.”

The collective achieved this by turning a traditional white cube gallery space in the Herbert Art Gallery in Coventry into an unofficial and illicit Irish pub—a síbín, or a ‘pub without permission’ that originated in Ireland around the turn of the 17th century. But this, the collective says, “is a place to gather outside the Sectarian divides.”

Installtion shot, Array Collective © David Levene, courtesy The Turner Prize

We approach the síbín through a circle of flag poles that reference ancient Irish ceremonial sites. Inside, the síbín is awash with paraphernalia one might not normally expect to find in a Belfast pub. Posters created by the collective adorn the walls and flags hang from the ceiling. Even the beer makes its own progressive points.

Here, in this dimly light, cozy bar, a video plays of an unfolding night of performative fun. Belfastards gather to drink and party; one by one, they take to the stage to compete for the title of Diva, some in drag, some in norm core T-shirts and jeans. Songs are sung, stories are told, stand-up routines are played out. Each performer is driven by the same desire; for Belfast to put its past behind and come together. On the walls is a pink poster, depicting a woman in high-heels, sat in a wheelchair. “All sorts of people need abortions,” she says in a speech bubble. A flag is stitched with the word REPEAL.

Cooking Sections installation shot © David Levene, courtesy The Turner Prize

Also competing for the prize were Cooking Sections, a London-based duo who have worked extensively in the Isle of Skye, Scotland, and who exhibited Salmon: A Red Herring at Tate Modern this summer. They have created quite a headache for Scotland’s fishing industries.

Via projections of circular fish farms which spin in pools of lights on the ground beneath our feet, Cooking Sections focuses on the evils of intensive salmon farming, the genetic modifications of the farmed fish, the way—a discombobulated voice tells us over an eerie soundscape—that “humans are the virus that the salmon can’t escape.” Cooking Sections have actively campaigned for galleries across the UK to take salmon off their menus, and have achieved extensive measurable gain, with Serpentine and Tate signing up.

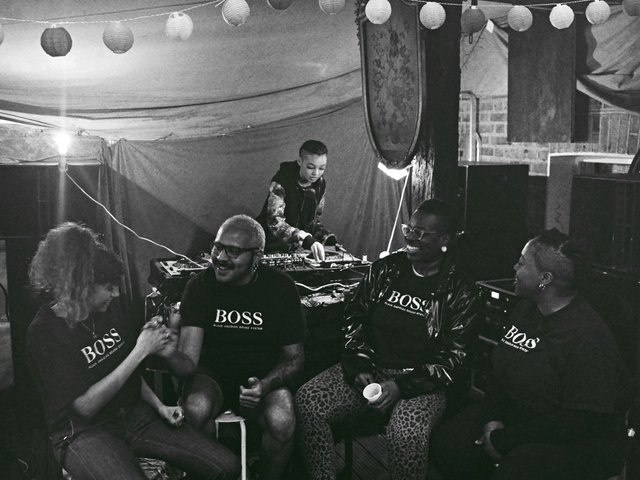

Alongside is London’s Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S.), a group of QTIBPOC —Queer, Trans and Intersex Black and People of Colour—who came together in Summer 2018 to “follow in the legacies of sound system culture”, a reflection of how marginalised groups have developed methods assembling against a backdrop of repression, also known as alternative club nights.

The exhibition on show here, which was first exhibited at FACT in Liverpool earlier this year, “considers the speaker as a totem for creating a sacred space.” In its centre, pools of water sit on huge speakers; as they throb to the hum of the music, so patterns dance on the water’s surface — a neat stand-in for the people who would normally tessellate together at the sort of sound event B.O.S.S. routinely hosts in alternative art spaces, but are notably absent in this rather sterile setting.

Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S.) installation shot © David Levene, courtesy The Turner Prize

Perhaps the most successful presentation in the show is by Hastings-based Project Art Works, an exhibition of mostly painted works by neurodiverse artists; profound internal expressions by people with mental health challenges, autism, learning and other intellectual disabilities. Some of the works on show here are deeply moving. But yet many of the works are stacked unseen together in the centre of the exhibition space, a statement, perhaps, of how such art is never properly considered by the wider world.

Finally, we see Gentle/Radical, a community project from Cardiff’s Riverside area, first established in 2017. The ambitions of the collective, which include social workers, are broad and diffuse; they put on events, from film screenings to performances to “grassroots symposia”, and hope to invite participants from every walk of life across Cardiff’s society to engage in art as a way to communicate and debate.

They “deliberately work in community contexts rather than mainstream cultural spaces to enable those routinely excluded from the arts to be met where they are,” the collective says. This is expressed via the form of filmed works, in which letters are read exploring personal experiences; one person remembers leaving their mother in a care home, for example, another meditates on the meaning of their Palestinian heritage. It is a laudable idea, but one ill-suited to and poorly communicated in the confines of a gallery setting—but, then again, that is the point.

Project Art Works installation shot © David Levene, courtesy The Turner Prize

The jury have made their message clear: the art of the individual is a thing of the past. The art of the collective is the thing of the moment.

The Turner Prize was once considered the crowning glory for a single name; a mainstream platform for a generation of British artists who soon gained global fame — Damien Hirst won it in 1995, Gillian Wearing in 1997, Steve McQueen, now perhaps Britain’s most recognised filmmaker, in 1999, and so on.

Seen together, the works here signal the evolving identity of the Turner Prize, and perhaps for the role of art as a whole in modern Britain. Are museums and galleries still where it is at, the exhibition asks—or should we look deeper?

Gentle/Radical installation shot © David Levene, courtesy The Turner Prize

The decision to award activists has sparked predictable debate across the cultural divides.

For its detractors, the prize is prioritising the hegemony of contemporary liberal politics over curiosity or discourse. Activist art of this type, they say, is one-dimensional, literal and allergic to nuance. It unquestioningly affirms truisms that are inarguable — that things are bad, and should be better, and we must all do more to achieve that. That we should meet and listen to each other in welcoming and tolerant ways. That intensive farming is bad. That vulnerable and marginalised people should be properly acknowledged. This is obvious, but does not make for a wildly involving or exciting show.

For others, the changing face of the Turner Prize reflects its own truism; that a lot of recent fine art has very little to do with the present moment. That much of it is still regurgitating, in form and in content, ideas and styles that were created by much better artists a century hence. That fine art has become so commodified, so market conscious, so in line with wealth and elitism that it has lost almost all purpose beyond basic decoration.

For its supporters, what the Turner Prize has chosen to celebrate creates a new vision for art which is pressingly of the moment; a type of decentralised, egalitarian form of work which is useful, utilitarian and utopic in concept — art detached from introspection, from ego and self-regard, one capable of helping us not to just consider but surmount the challenges we face.

The founding concept of the Turner Prize was to award an artist born, living or working in Britain for an outstanding exhibition or public presentation of their work anywhere in the world exhibited over the previous year.

This began to change in 2015, when the London-based community collective Assemble became the first group to win the show. But the change quickened over the past two editions of the show, when no single outright winner was awarded.

In 2019, the four finalists staged something of a public rebellion by announcing at the award ceremony that they would prefer to each share the prize, and prize money, in equal parts, rather than see one artist anointed.

In 2020, the pandemic effectively made art exhibitions impossible for months on end, prompting the Tate museum group, which organises the prize, to cancel the award outright and instead equally distribute £100,000 amongst 10 artists.

Tonight, a winner has been announced, but a stirring debate remains — should this have even been exhibited in a museum at all, or in the communities where the artists truly belong?