For Haitians who endured the cataclysm caused by the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July and the major earthquake that struck a month later—not to mention the 2010 earthquake that killed 300,000—life is nightmarish. “Nothing is working right now. People risk their lives every time they go out of their house, whether they’re rich or poor,” says the dealer Axelle Liautaud, now living in New York after gangs kidnapped her sister (who was later reunited with her family). Her stately wooden house, filled with art, however, was burned to the ground.

“I have a museum in my heart because I have all this stuff that no longer exists,” she says. So far, the gangs that roam Port-au-Prince are not looting art, she adds, “It’s easier to get cash from kidnappings.”

In Miami, now Haiti’s second cultural city by default, there is no single Haitian style. Tomm El-Saieh, born in Port-au-Prince, whose mother runs a family art gallery there, makes large, meticulous and abstract paintings that are unusual for Haiti’s culture of storytelling and symbolism.

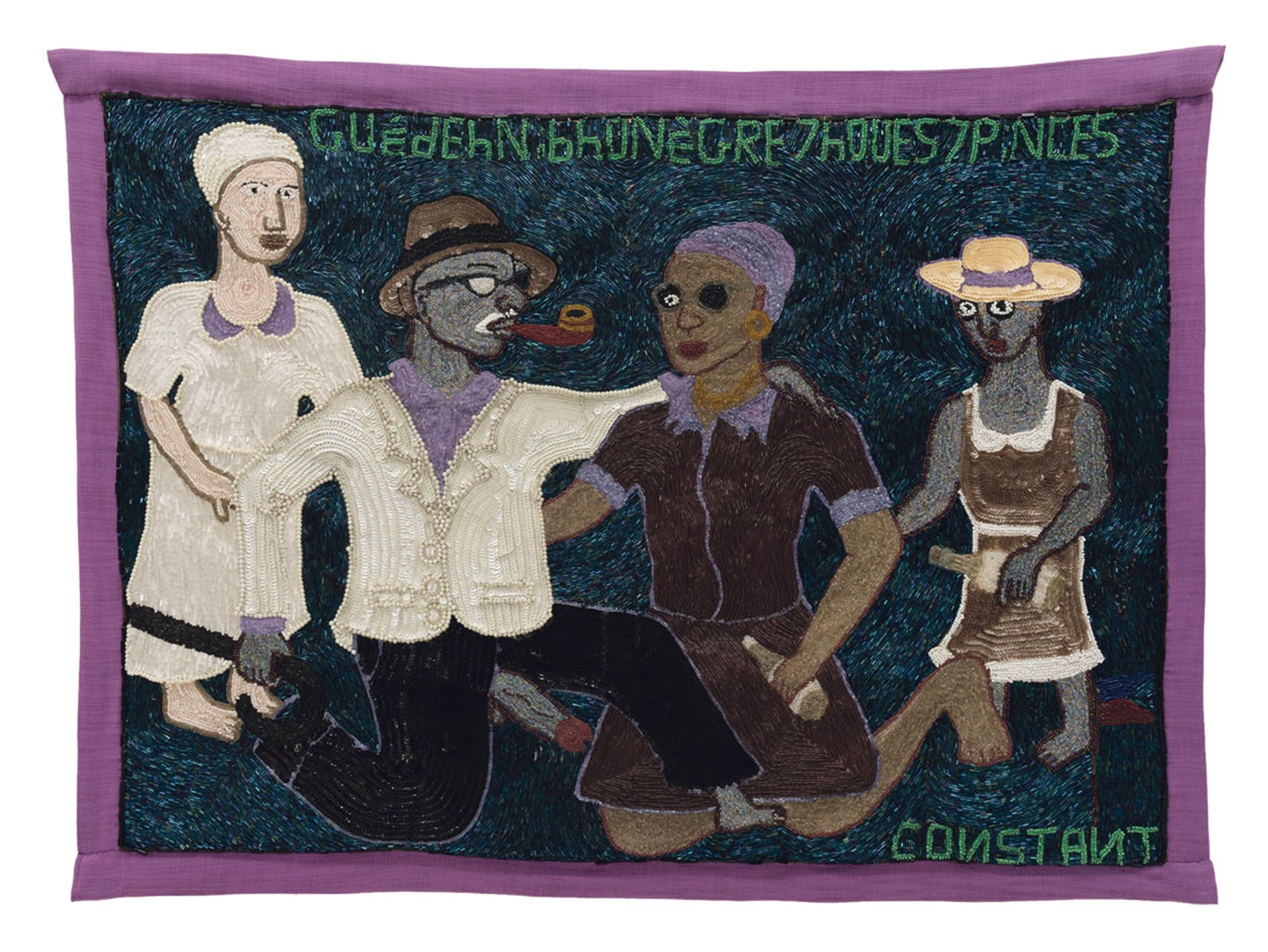

El-Saieh is also a partner in the Miami gallery Central Fine, which represents Myrlande Constant, who trained as a seamstress and now makes vodou (voodoo) flags that traditionally fly at vodou temples in Haiti. Sewn with luminescent thread and beads, the flags depict figures and symbols—borrowed and imagined—from Haitian cosmologies. The flags filled Luhring Augustine’s stand at the Art Dealers Association of America’s fair in New York in November.

Myrlande Constant’s Ghuede (2003), a voudou flag made from beads and sequins Courtesy of the artist, Central Fine, Miami Beach, and Luhring Augustine, New York

At Art Basel in Miami Beach, Luhring Augustine will show an abstract painting by El-Saieh. Art by Haitians is all over Miami and is being mapped by the Port-au-Prince dealer Gaël Monnin, who recently opened a space in Miami.

The artist Edouard Duval-Carrié, who has lived in Miami for 22 years, is co-organising a show of Miami artists at the Bakehouse Art Complex and showing his own work at the Faena Hotel in Miami Beach. Haitians are part of Miami, he says. “The city realises that they just cannot erase them. Even the museums have started collecting Haitian art very seriously.”

Dangers and logistical challenges

As with the French in London after Dunkirk, Duval-Carrié predicts, “Miami will become like a seat of the government in the Second World War—I see that coming at a fast rate.” Not too fast, though. Duval-Carrié says he was unable to bring Rel, an exhibition of Haitian artists that sold well at the intrepid Centre d’Art in Port-au-Prince last winter, to Miami. The dangers and logistical challenges were simply too great.

During the fair, Constant will be in Port-au-Prince, where food, water, medicine and fuel are scarce. And when mobile phones can be charged, there is often no signal. Fear of kidnapping keeps the streets quiet, when they are not exploding. Collectors, dreading fires that cannot be put out, are shipping art abroad. Haitian collections could end up in Miami, New York, Paris—or Denmark, where the film director Jorgen Leth’s much-exhibited and admired collection is in storage. A few galleries are open, although the tourists and relief workers who bought art during earlier crises are gone.

In Port-au-Prince, the Ghetto Biennale, held concurrently with Art Basel in Miami Beach since 2009—because Haitian artists could not obtain US visas to attend the fair—has been a notorious salon des refusés for the urban poor. A group of artists from the Grand Rue calling themselves Atis Rezistans and inspired by vodou and the chaos around them made sculptures from found materials, including assemblages with human skulls and bones. That confab will not happen this year, though the Ghetto Biennale has been invited to participate in Documenta 15 next year, says the British artist Leah Gordon, a co-founder of the event.

Herold Pierre Louis, 25, from the youth offshoot of Atis Rezistans, Ti Moun, sells his imaginative satirical paintings on cardboard of Andy Warhol and nude gay tourists on Facebook. “The bandits have killed people everywhere, I’m very scared to say,” he writes in an email. “It’s me who helps my parents [who do not] work [so] if I don’t sell anything [they] can’t eat.”

Pierre Louis is from the next generation after the artists who were included in Pòtoprens: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince, a survey of artists of the Grand Rue, including Constant, organised at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn in 2018 by Edouard Duval-Carrié and Leah Gordon. The show amazed New Yorkers and defied the more conservative Haitian diaspora in south Florida when it travelled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami in 2019.

Gordon, Duval-Carrié and André Eugène of Atis Rezistans are holding evens in Miami this week to mark the launch of a new edition of that show’s catalogue. “It’s a way of their work escaping Haiti,” Gordon says.

• A conversation about Pòtoprens: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince, will be held at NADA Miami, Ice Palace Studios, 1 December, 4pm

• A panel discussion and celebration ofPòtoprens will be held at the Center for Subtropical Affairs, 7145 NW 1st Ct, Miami, 1 December, 7pm