This year is the bicentennial of Missouri’s statehood, marked by the Saint Louis Art Museum’s exhibition, Art Along the Rivers (until 9 January 2022) and accompanying catalogue. To counter settler narratives about the formation of the state—an Anglo-American construct of space and time—curators M. Melissa Wolfe and Amy Torbert aimed to insert the cultural contributions of Native Americans, African Americans, women and others who experienced the same land. They have therefore centred the project on that shared terrain: what they term “the confluence region” surrounding St Louis. Drawing from more than 50 regional institutions, they have assembled remarkable objects produced and collected over 1,000 years in the lands demarcated by the Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio Rivers. The authors explore the presence of Native Americans in the confluence region and humankind’s interaction with that landscape throughout the book, culminating in the final chapter analysing works of art protesting the displacement of the Indigenous people and environmental destruction.

They capture that uneasy dynamic between people’s futile efforts to impose their will on the earth and the power of nature to rebound

The Osage (Wazhazhe) people called this land of the rivers home. When the US military arrived there around 1800, they presented uniforms as diplomatic gifts, which became symbols of status adopted by the native women as bridal dress. After Missouri achieved statehood, thousands of their tribe were forcibly relocated via the Trail of Tears to reservations in Oklahoma, where they lacked access to familiar materials. Determined to maintain traditions, unidentified Osage women created Wedding Coat and Plumed Hat by fashioning a Western-style coat and embellishing it with ribbon, horsehair and feather, an assertion of female identity and resistance. To quote the authors: “The garment, fully folded into Osage culture and aesthetics and typically passed down to the family’s next generation, perpetuated associations of status that Osage people forged during the previous centuries in Missouri.”

The Osage (Wazhazhe) repurposed US military uniforms as bridal outfits asserting female identity and resistance. Courtesy Denver Art Museum

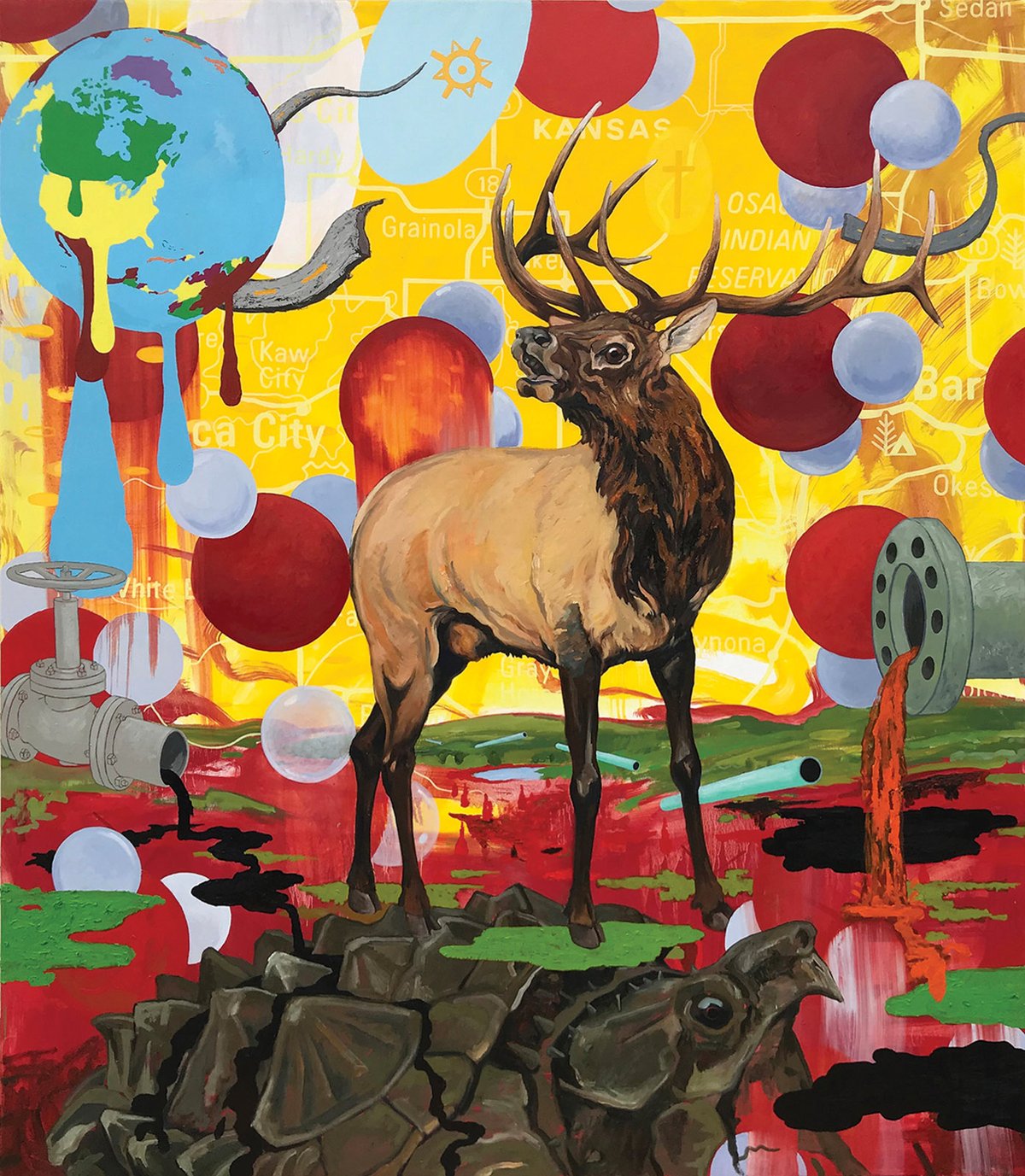

Almost a century later, the Osage artist Norman Akers’s Dripping World (2020) offers an updated meditation on the Trail of Tears. The painting’s background features a map of Osage territories “joined by personal and cultural symbols that tether the colonialising process of Indian removal to the consequences of commodifying natural resources”. Pipes spewing oil and industrial waste onto the sacred terrain make visible environmental concerns that Akers shares with other featured artists. For example, two photographs—by Sam Fentress and Emmet Gowin—depict Times Beach, Missouri. Founded in 1925 as a resort community, it grew to 2,500 year-round residents who conducted their daily lives unaware that dioxin—a toxic chemical—had been sprayed on their roadways. By 1982, Times Beach was declared uninhabitable and evacuated. In search of religious road signs, Fentress photographed its homely white billboard reading “John 3:5”, situated between the architectural debris left by the fleeing townspeople and the strand of trees whose foliage hints at the promise of renewal. From an airplane, Gowin looked down on this depopulated area, intending to reveal the aftermath of destruction. Yet his aerial view bathed in early-morning light and dominated by the grid of townships and ranges— the settler’s method of imposing order on the terrain—fails to expose dioxin’s deadly traces.

Like their 19th-century predecessors George Catlin or George Caleb Bingham (the latter featured here), Akers, Gowin and Fentress capture that uneasy dynamic between people’s futile efforts to impose their will on the earth and the power of nature to rebound. This bicentennial celebration of art created over a millennium in the confluence of the rivers contains both dire warnings about humankind’s transgressions and signs of hope for the future.

• Amy Torbert and M. Melissa Wolfe with contributions by Beth Rubin, Art Along the Rivers: A Bicentennial Celebration, Hirmer Publishers, 224pp, 200 colour illustrations, £35 (pb), published 28 October

• Katherine Manthorne is professor of art history at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Her books include California Mexicana: Missions to Murals, 1820-1930 and Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex (University of California Press 2017 and 2021 respectively)