The death of the respected British photojournalist Tom Stoddart was annouced by his family on Wednesday. He was 67.

In a statement, Stoddart's family said: "It is with great sorrow that we announce the passing of Tom after a brave fight against cancer. He felt blessed that he had found true happiness with [his wife] Ailsa. The family kindly ask that their privacy be respected at this time.

"Tom touched the lives of so many as a brilliant, compassionate, courageous photographer whose legacy of work will continue to open the eyes for generations," the family said. "He gave voice to those who did not have one and shone a light where there had been darkness."

Here, the British photographer Peter Dench pays tribute to his friend and mentor:

Tom Stoddart once handed me his Leica M6 camera. It was the first Leica I ever held. I remember raising the viewfinder to my eye: “Wow Tom, everything looks amazing,” I said to him. “Not everything, Peter,” he replied in his soft Geordie accent.

Tom Stoddart worked as a photojournalist for over four decades, publishing for Getty and publications including The Sunday Times and Time magazine amongst many others.

Throughout his career, Tom captured some of the most devastatingly powerful and informative images of a generation, from the fall of the Berlin wall to the wars in Lebanon and Iraq, from the election of South African president Nelson Mandela to the bloody siege of Sarajevo.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, Tom’s photographic opus iWITNESS, published by Trolley Books in 2004, is the Encyclopedia Britannica. Page after page of starving people, lost people, people in physical pain, grieving people, innocent people, trapped and battered people, people decimated by disease and dead people.

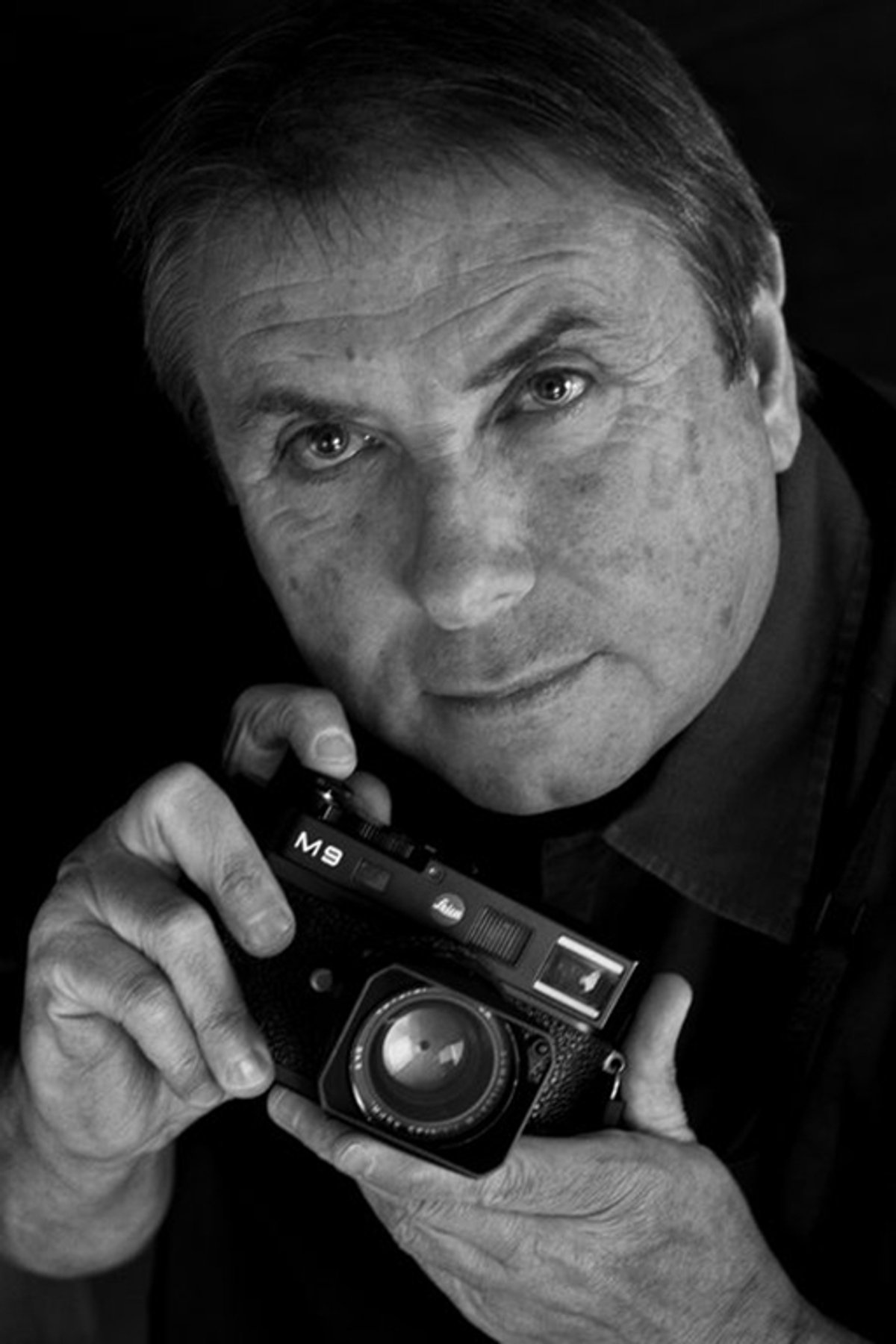

Tom Stoddart (left) with his friend Peter Dench © Maria Dal Pan

But just as important to Tom were the pictures that show hope, laughter and life. His book, Extraordinary Women (published by ACC Art Books in 2020), focusses on the strength and resilience of those who are often represented as vulnerable.

In 2012, 78 of Tom’s signature images were put on display outside City Hall, the mayor of London’s office on the South Bank of the Thames. Around a quarter of a million visitors, many of whom were in town for the Olympic and Paralympic Games, are estimated to have witnessed the exhibition.

Success for Tom was judged by public response. “The best feeling was to be unrecognisable among the work and listen to the comments,” he once told me. “I want to show people things that they thought they knew about.”

When I took my daughter, then aged seven, she gave her own affirmation: “I think I understand why other children want to live in England,” she said.

As a source of inspiration, Tom’s photograph of Meliha Varešanović, walking proudly and defiantly to work during the siege of Sarajevo, was hung outside my daughter’s bedroom. I was hoping she would meet Tom many times as an adult. I’ll make sure she knows everything about him.

Meliha Varesanovic defiantly walks to work during the siege of Sarajevo, Bosnia 1995 © Tom Stoddart

Born in Morpeth, Northumberland, in 1953, the son of a farm worker, Tom’s morals were instilled by his mother and his headmaster at the mixed comprehensive school he attended in the fishing village of Seahouses.

At aged 17, Tom saw an advertisement in the Berwick Advertiser for a photographer. He had shown an aptitude in English classes at school and saw the Berwick Advertiser as a potential platform to build a career as a reporter. He successfully applied, more down to having passed his driving test than possessing photography skills, he would say.

After an assignment photographing on location at a Women’s Institute party, he knew photography was for him, rather than a life behind a typewriter.

Tom was seriously injured whilst photographing heavy fighting around the Bosnian Parliament buildings in Sarajevo during the civil war that engulfed Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

As a result, one of his legs became one and a half inches shorter than the other, whilst his shoulder was fitted with a titanium plate. Other photographers of his generation ceased working or eased their passage into old age by educating the young. But Tom never had any intention to stop shooting. Working closely with Getty Images, he remained determined to create a visual legacy. Through his exhibitions, books and collections, he will be remembered in history.

And I will remember him, too, for everything he did for me. When my wife was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016, the first person I told was Tom Stoddart. I’m not sure how he felt about this — but it felt the right thing to do.

I first met him in 2000, when I joined the Independent Photographers Group photo-agency which Tom was part of. For some unfathomable reason, he took an interest in me and my career. He has been a constant guide ever since.

He was never a father figure; he was far more than that. He was to me, and I suspect many others, a Godfather of photography. He once told me: “Pete, there’s no such thing as a guardian angel. There’s stupidity, experience, and luck, and I got lucky, very, very early”.

I am very, very lucky to have known him. And devastated to have lost him.

Cheers for everything, Tom.