In 1954, Ernest Hemingway won the Nobel Prize for literature. By then, the American writer was spending most of his time at the Finca Vigía, or “lookout farm”, he had purchased just outside of Havana in Cuba in 1940, having recently survived not one, but two plane crashes.

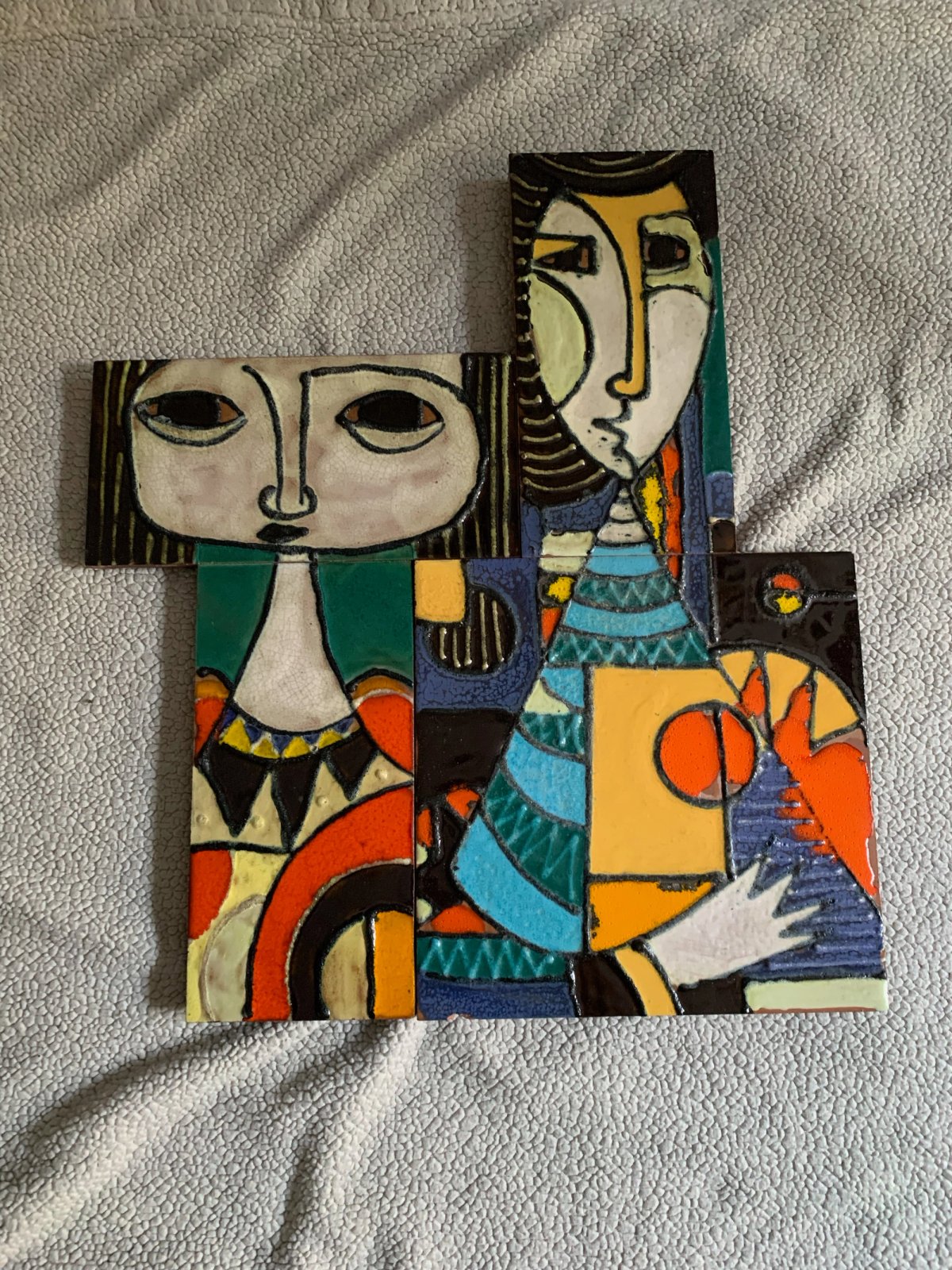

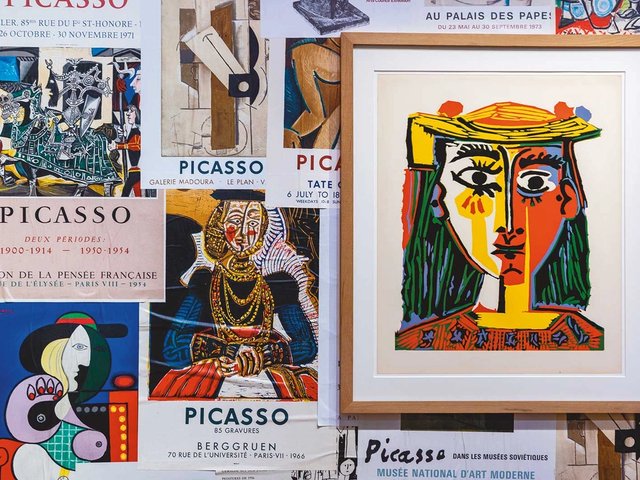

Around this time, Picasso is thought to have gifted Hemingway a semi-abstract, brightly glazed ceramic depicting two figures—possibly a man and a woman. A new podcast is now investigating whether that piece, consisting of four large tiles that fit together like a puzzle, was later given to the one-time US National Football League (NFL) player and drug smuggler, Steve Kough, as payment for a drug run financed by the Colombian narco-trafficker Pablo Escobar—and whether the work is indeed by Picasso.

It was in 1989 that Kough apparently acquired the ceramic, which he nicknamed Fred and Betty.. “Calling it that was also code,” explains the journalist and crime author Leah Carroll, who co-wrote the podcast, Hemingway’s Picasso, with the show’s producer Pallavi Kottamasu.

Kough’s NFL career had derailed after a four-year stint in prison in the early 1980s where he had met Joe Pegg, a kingpin of Escobar’s cocaine cartel and his alleged entry into the drug underworld. According to the podcast, in 1989 Kough was on a run, smuggling electronics into Cuba and drugs and art back into Miami. During this trip, Kough claims he was driven to the Finca Vigía, which Hemingway had left in 1960, a year before his suicide, and which was later taken over by the Cuban government. There, Kough was met by a curator, who was “clearly really upset about having to deal with this drug dealer”, the journalist Joe Flood tells Carroll in the podcast.

Kough was supposed to exchange the work for cash, but shortly after he took possession of it, Escobar’s Medellin cartel fell apart. “Basically every single pillar of this […] whole shaky edifice just collapses […] and so Steve is left with the piece,” says Flood, who had attempted to tell Kough’s story several years ago, driving with him from Iowa to Miami in 2014 in a bid to sell the alleged Picasso ceramic during Art Basel’s Florida fair.

The ceramic was not Kough’s first dalliance with the art world.

While on trial in Detroit for conspiracy to distribute marijuana in 1982, Kough had started frequenting the Detroit Institute of Art, which was near the courthouse. “I used to go in there and take my lunch break,” Kough recalls in one of 25 tape recordings he made before he died in 2018. One day, Kough says he noticed that dozens of works of art were being removed, so he asked a guard why. The reply came: “The Dutch queen is coming to open up that whole wing […] it’s going to be a couple months for them to renovate the whole wing […] with all the plaster and repainting and re wallpapering.”

At that moment, Kough hatched a plan to steal some art. Wearing white workman’s overalls he strode into the museum, declaring he had come to plaster the East Wing. “They let the wolf in the wolf house because [in] this climate controlled vault, there was an air shaft that wasn’t sensor detected and had no alarm system in it. And I said, ‘fuck it. I’m gonna, I’m going to break into this son of a bitch’,” Kough says in the recording.

After smearing Vaseline over his whole body and wriggling through the air shaft, Kough landed in a storeroom full of wooden crates. “The first wooden crate I came to, I popped it open. And, uh, the first three paintings were a woman weeping and Frans Hals laughing boy, and a view from the shield by Cuyp,” Kough recalls. “I put them around a rope around my body and [dragged] them like [it] was my tail coming out the back end.”

As Carroll notes in her podcast, the paintings were not quite as valuable as Kough had initially thought. A Woman Weeping was not by Rembrandt, as the Detroit Institute of Arts had believed, but later attributed to the circle of Rembrandt; while Frans Hals’s Laughing Boy was downgraded to “in the style of Hals”. Aelbert Cuyp’s River Scene at Dordrecht was also attributed to a follower. A fourth painting, Lucas Franchoys’s St. Michael in Combat with the Rebel Angels, was also stolen, though Kough's links to the work have not been proven. The four paintings were insured for just $310,000—not the millions Kough had anticipated his haul was worth.

The paintings were eventually recovered in December 1989 and January 1990 in connection with an undercover drug investigation in Miami, according to reports at the time. An art dealer named Anna Barnes testified during her own trial that she had received the paintings from an unknown Michigan drug dealer and kept them in a Miami safe deposit box. Kough was never named in connection with the case, though he had allegedly offered the paintings to Pegg—on behalf of Escobar—while in prison.

As for the so-called Picasso ceramic, which Kough believed could be worth millions (though Picasso’s ceramics usually sell in the tens of thousands), it is now in the hands of Kough’s son, Stevie.

It was while interviewing Stevie Kough at his house in Huntington Beach in California that Carroll first saw the ceramic, stored in a green US military medic case, which Kough senior was convinced was a relic from the botched Bay of Pigs attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro’s regime in 1961. So does she believe it’s a genuine Picasso? “I’m not an art expert but I was very impressed by it,” Carroll says. “All I’ve been hearing about is this Picasso for months and months and then suddenly there it is, and not only that, it was so much bigger and more vibrant than any of the pictures I had seen to that point do it justice. It was like the ark of the covenant had just dropped in my lap.”

Her quest to authenticate the work continues, as does Kough junior’s mission to, in his dying father’s words, “Get it done. Sell Fred and Betty.”

• Episodes 5-8 of Hemingway's Picasso will air on Mondays from 22 November-6 December. An article covering the latter half of the series will be published in our Art Basel in Miami Beach 2021 dailies and online.