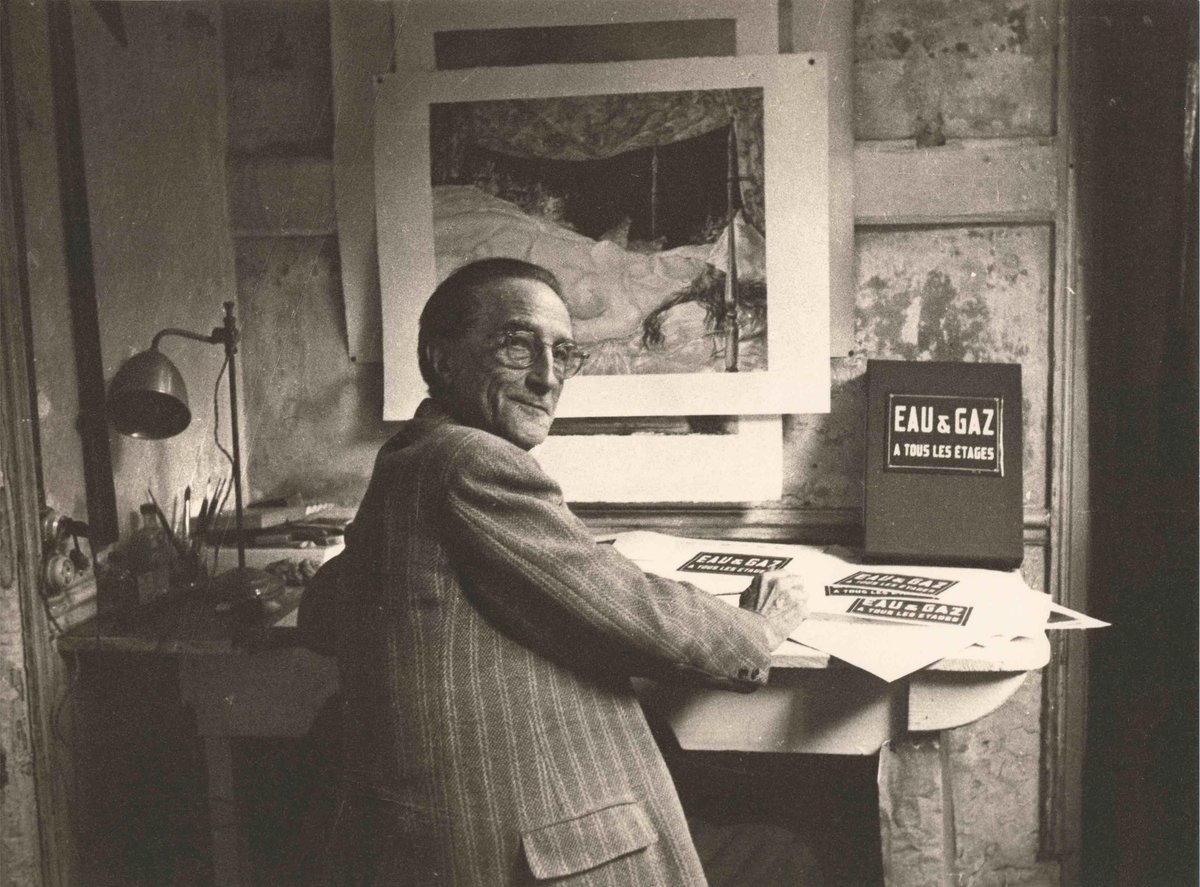

Scholars and devotees of Marcel Duchamp will relish a fully authorised facsimile of the important first monograph and catalogue raisonné entitled Marcel Duchamp by the art historian and critic Robert Lebel. Hauser & Wirth publishers have reissued the Grove Press English edition of the monograph—translated from the French edition Sur Marcel Duchamp—which was released in 1959.

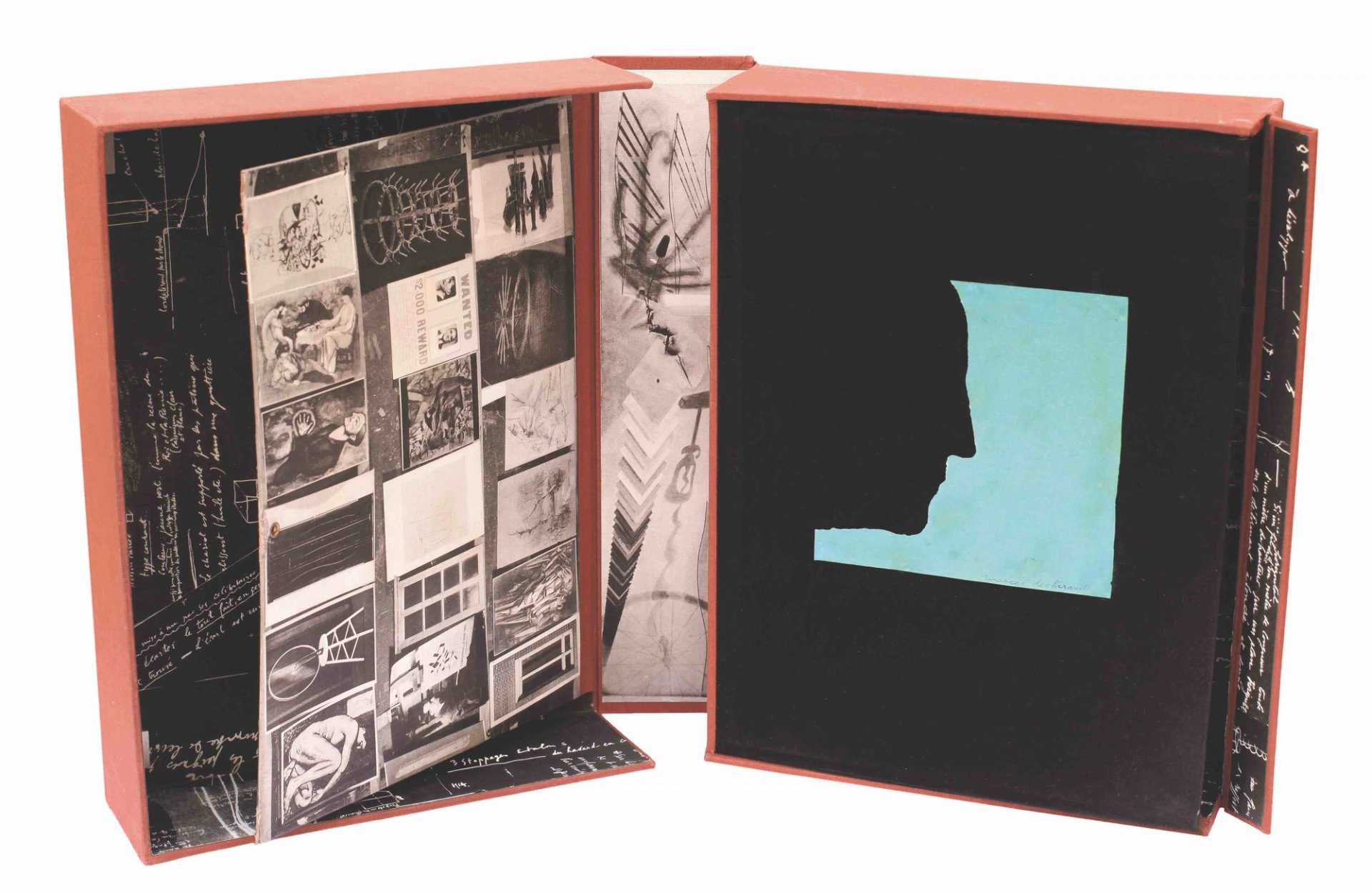

The comprehensive survey—produced in collaboration with Jean-Jacques Lebel, Robert Lebel’s son, and the Association Marcel Duchamp, representing the artist’s estate—includes “every known work by Duchamp” along with 50 personal photographs of Duchamp and his circle. “Re-creating a title that was fabricated more than 60 years ago required specialists; fluid, the [London-based] curatorial-design studio helped by art historians and book specialists Axel Heil and Margrit Brehm, led this effort. They re-recreated the original typefaces as digital fonts, positioning each letter and image exactly where they were in the original,” says a press statement.

The facsimile of the historic edition is accompanied by a supplement co-edited by Jean-Jacaues Lebel featuring a series of texts that explore the relationship between Duchamp and Robert Lebel and consider the critical reception of the book. We pick out three “takeaways” from Robert Lebel’s original texts.

A 1959 deluxe edition, press copy. Galerie 1900-2000. Artwork by Marcel Duchamp. Association Marcel Duchamp / ProLitteris, Zurich, 2021 Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Publishers

Rupturing Cubism and Futurism

Chapter: “Bonds and Breaks: First Attempts, Cubism, The Nude Descending a Staircase”

Robert Lebel explores how Duchamp ploughed his own furrow beyond Cubism and Futurism, discussing how Nude Descending a Staircase (2012) breaks free from the artistic rules of the day.

“The conception of the nude was certainly the result of the convergence into Duchamp’s mind of the most various interests among which we must not overlook the cinema still in its infancy… since he was determined to put an end to the continual discussions about Cubism he saw that it could only be done by going it one better.

“Therefore he introduced right away a kind of movement which had been completely lacking up to then. By recognising this deficiency and promptly providing for it, Duchamp was able to save himself the effort and time the Cubists spent in circling round and round the immovable object, and he passed directly from ‘semi realism’ to the ‘non-figurative’ expression of movement…. Morphologically however the Nude is not related to Futurism with which Duchamp never had any contact.”

Making a splash in the United States

Chapter: “1913- Triumph at the Armory Show and the rejection of retinal art”

The Armory Show was held at the Sixty-ninth Regiment Armory in New York early 1913, attracting more than 100,000 visitors, most of whom stood in line to see Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. “The painting provoked countless articles and caricatures,” writes Lebel but it also catapulted Duchamp into the premier league of artists.

“Duchamp sent four paintings to it [The Armory Show]: Nude Descending a Staircase, Sad Young Man in a Train, Portrait of Chess Players and The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes. The Armory Show, soon after it opened in February 1913, aroused immense curiosity and indignation of which one of the principal sources, because of its title, was the Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), which immediately became famous. It eventually found a purchaser, as did the three other works by Duchamp who was unexpectedly promoted from the rank of artiste maudit [damned artist] to that of a painter with a clientele.”

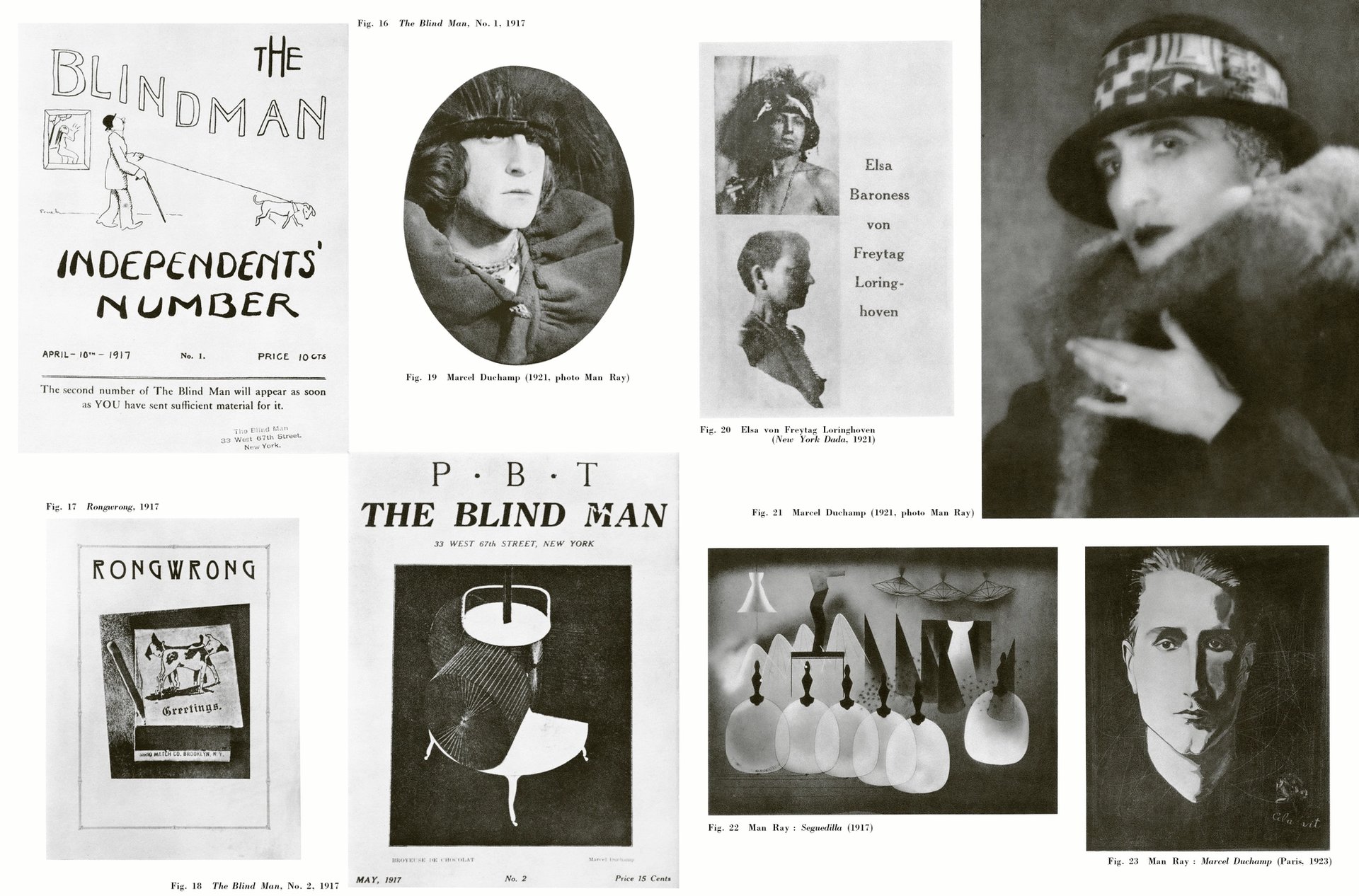

Spread from Hauser & Wirth Publishers' 2021 facsimile of Marcel Duchamp, the artist's 1959 monograph. Artwork by Marcel Duchamp © Association Marcel Duchamp / ProLitteris, Zurich, 2021. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Publishers

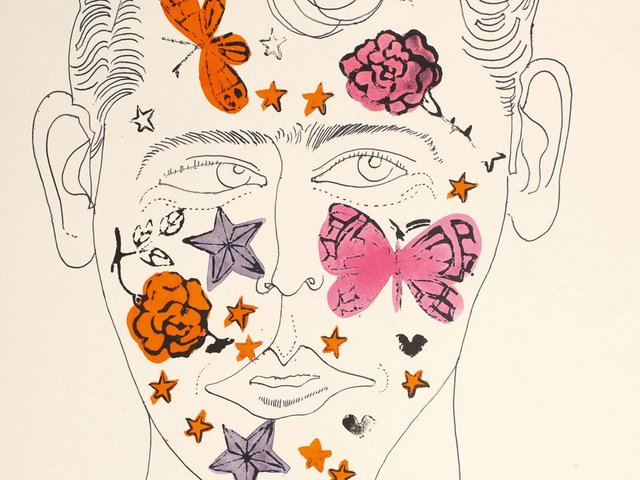

The origin of Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp’s female alter ego

Chapter: “Final Farewell to Painting: Dada, the Rotatives, Rrose Sélavy”

Lebel outlines how Duchamp’s female persona was born, describing how the second ‘r’ in her name was added in 1921 when her signature was added to Francis Picabia’s collage L’Oeil Cacodylate.

“[In 1920] after having thought first of adopting a Jewish name he took the pseudonym Rose Sélavy with which thenceforth he signed his works… But the next year in Paris the name acquired an additional implication when after the last letter of Picabia’s signature on the Cacodylactic Eye (which the artist had spelled ‘Pis qu’habilla’), Duchamp wrote ‘Rrose Sélavy’ (‘arrose, c’est la vie’). If the term is always so flexible, it verges so to speak, toward the masculine by emphasising this time the servitude of the ‘malic’ function.

“However that may be, the fictitiously female pseudonym was accompanied by a physical feminisation achieved on the cover of [the magazine] New York Dada in 1921 where Duchamp appeared as a woman in the portrait which embellished the bottle of Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette.”

Marcel Duchamp, facsimile of the 1959 English edition, Robert Lebel with texts by Marcel Duchamp, André Breton and H.P. Roché, Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 192pp, £100.00 (hb)/Supplement edited by Jean-Jacques Lebel and Association Marcel Duchamp