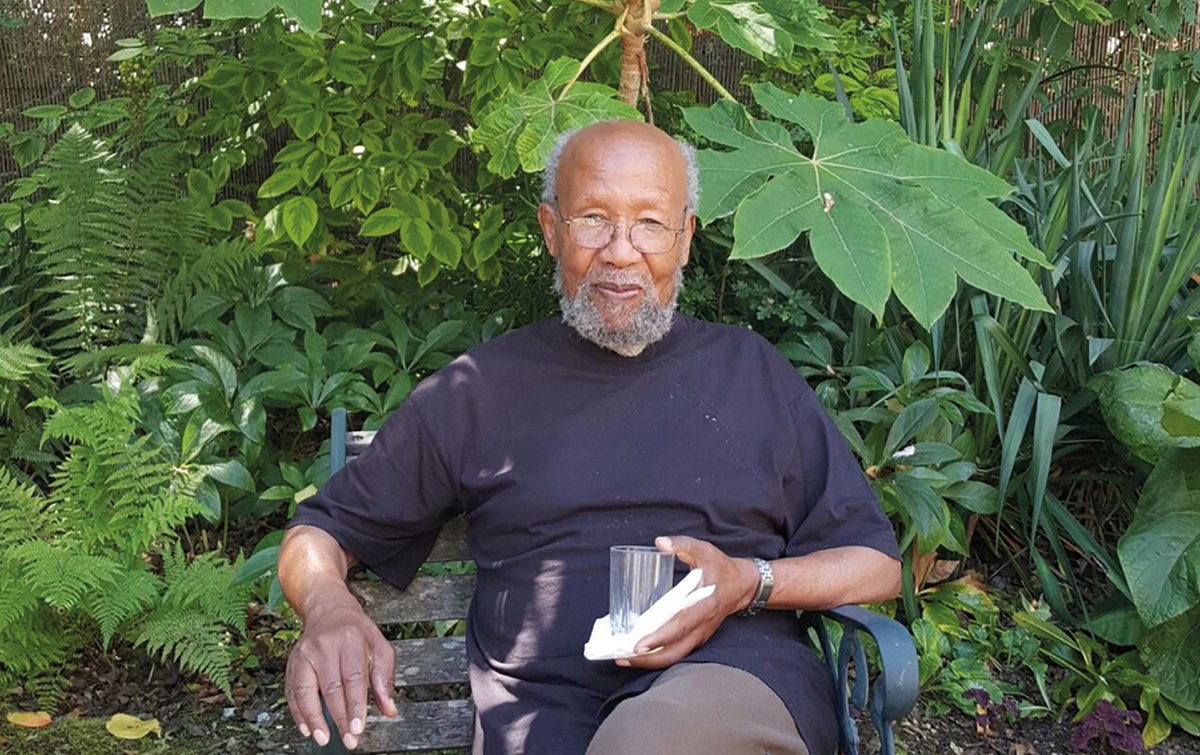

“Ibrahim El-Salahi is a born story-teller,” writes his fellow Sudanese artist, Hassan Musa. “He is full of stories when he narrates, writes or draws, not to mention the tales that are told about him.”

El-Salahi was born in 1930 in Omdurman in Sudan. He studied at London’s Slade School of Art in the 1950s, creating Modernist paintings influenced by the prevailing British style. But on returning to Khartoum, he found little interest in an exhibition of his work, so he started incorporating Arabic calligraphy and other aspects of Islamic culture to help connect to his Sudanese audience. He became the leader of a group known as the Khartoum School, which merged Western, African, Arab and Islamic artistic traditions.

El-Salahi became involved in arts administration in Sudan, but in 1975 he was accused of participating in a failed coup and was imprisoned without trial for over six months. Held in the notorious Kober prison, he was forbidden to write or draw. But El-Salahi continued to work secretly, making small sketches on the paper bags that the food was distributed in and burying them in the sand to hide them from the guards.

After being released from prison, El-Salahi moved to Qatar before settling in Oxford in the late 1990s. Recent years have seen an increasing recognition of his pioneering role in African Modernism, including a major retrospective at Tate Modern in 2013, the London museum’s first devoted to a living African artist. His work is held in the collections of the Tate, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art, among many others.

Now 91, El-Salahi continues to create work, including a recent a series of small drawings made on the back of the packets of medicine he takes for his chronic back pain—named the Pain Relief series. In the past few years, he has started to create sculptures—a series of abstract trees made in different sizes and materials, first shown in 2018 at the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, and on view in Frieze’s sculpture park this week.

The Art Newspaper: You’ve been making art since the 1950s—but you only made your first three-dimensional work a few years ago. Why did you decide to do that now?

Ibrahmi El-Salahi: I don’t know, really. But I think maybe because of what is happening in Africa, with soil erosion and climate change. We used to have a haraza tree that my father grew in front of the house. It was very kind to us and gave us fruit; it was fruity all the year through. But then it started dying as the climate changed. It became old and a brother of mine had to cut the stem down.

Apart from this, I have become more aware of the line drawings that I do. [The form of the trees was taken from his drawing, Meditation Tree (2008)]. So it’s trying to give a chance to the simple line, which surrounds the form in the drawing, to grow up.

El-Salahi’s Meditation Tree (2018), presented by Vigo Gallery in Frieze’s outdoor sculpture show, testifies to the central role that trees—particularly the haraza, found on the banks of the river Nile—play in much of his work Photo: courtesy of Vigo Gallery; © Ibrahim El-Salahi

The trees all have the same form but are different materials and sizes. Why is this?

It’s just like people! I liked the idea that we humans are all unique but also essentially the same with little variations, a little bit of a different colour, a little different in size and shaped by our age and environment. As these Meditation Trees age, they will crack, grow patina, maybe need a bit of repair every now and then, much like we do. I like the fact that they will change with time and each one will be different.

The haraza tree appears in dozens of your paintings and drawings. Why is this motif so important to you?

It’s symbolic. The haraza grows by the banks of the Nile and goes against the grain. When the other trees and plants blossom, it is quiet but when the dry season comes it bears fruit and flowers. I feel it is a bit like artists in general and me in particular.

You’ve spoken about how your drawings and paintings often start from a nucleus and grow outwards, with no plan. How did the process of making the sculptures differ from this? What were your experiences of working in this different way?

It’s the same for everything. It’s the idea of growth from a seed, to develop and take form. Like human beings, like all beings, they start from a sperm and then they grow. It’s the same thing for the idea of freedom. If you believe in the rise of humans everywhere, that has to spring up and take shape into a better life, and that’s what I hope will happen everywhere.

Are you planning any more sculptural works in the future?

Maybe!

“I use my eyes to see and understand, and to comprehend. But my art comes from within”Ibrahim El-Salahi

How has the lockdown been for you? Have you continued to make work?

Yes, I keep working all the time. I make small, small works, but continuous. I never stop.

From your time in prison to your more recent struggles with back pain, you have continued making art. Is image-making something you feel compelled to do? You’ve described it as a form of meditation or pain relief.

Yes, my work comes from within. I use my eyes to see and understand, and to comprehend. But art comes from within.

You’ve lived in Oxford since the late 1990s. Has the English landscape found its way into your work?

Very much so.

Your sculpture is being shown in Regent’s Park. Did you ever visit the park when you were a student at the Slade? What are your memories of it?

Yes, I used to visit because I had some friends living in the surrounding area. I love the flowers, the trees, the lawns, the beauty and the greenery. I used to watch workmen working on the lawns and the flowers. I used to love to see and observe and enjoy.

What do you miss most about Sudan?

The people. The festivals. The life. Everything which I grew up with as a child I miss, terribly so.

• Ibrahim El-Salahi’s tree sculptures can be seen in Frieze Sculpture in the English Gardens of Regent’s Park, until 31 October; and in the exhibition Bold Black British at Christie’s, 8 King Street, until 21 October