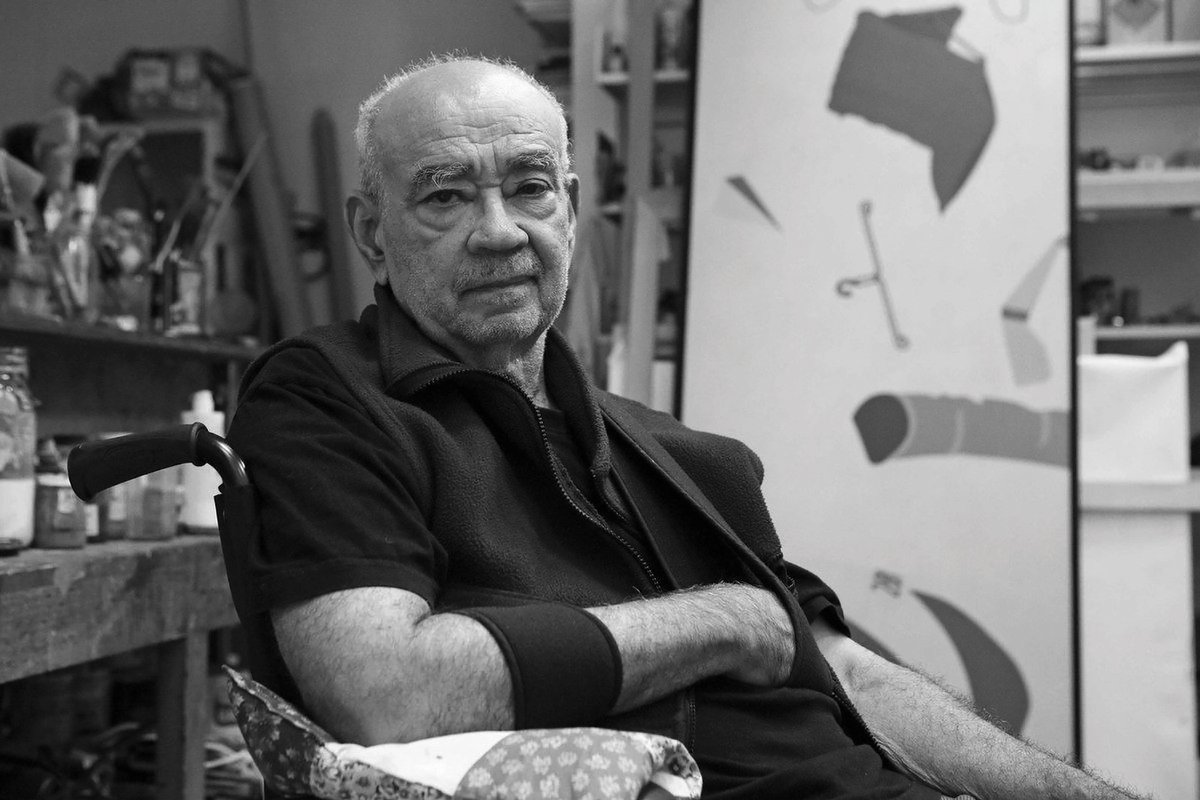

Hervé Télémaque’s work teems with disparate imagery and words, informed by his broad cultural references. Born into an artistic and literary family in 1937 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Télémaque moved in 1957 to New York, where he encountered Abstract Expressionism and experienced a culture shock that would shape his work. “My problem was with the US, the Anglo-Saxon world, the English language and racism,” he says. Télémaque arrived in Paris in 1961 and reacted against what he saw as the mediocre hangover of the pre-war Paris school of painting. “This is the problem I had when I left New York, where I knew the great American Expressionists well: to suddenly find myself in front of minor Parisian lyrical abstraction.” In response, he created a style close to Pop Art and founded the Narrative Figuration movement with artists including Bernard Rancillac and the critic Gérald Gassiot-Talabot. That commitment to responding to the world around him, his personal histories and social concerns, has run through his work in painting, sculpture and collage ever since. Télémaque is the latest senior artist to be given overdue recognition in the UK in the form of an exhibition at London’s Serpentine Galleries (until 30 January 2022).

The Art Newspaper: You came from a literary family. Did you ever hope to be a poet or was it always visual language with which you wanted to express yourself? Your paintings feature a lot of words.

Hervé Télémaque: Yes, I come from a family of artists, with an aunt who was a pianist and an uncle who was a poet. Like all young boys, I started by writing a few bad poems myself. But the central figure in my family was my mother, who always had a book in her hand and read most of the time. So, for me, it was natural to refer to her constantly—she was more important than my uncle. I did read a lot of poetry—people like Saint-John Perse, for example—and all the Haitian poets. Is that what nourished my painting afterwards? I don’t know.

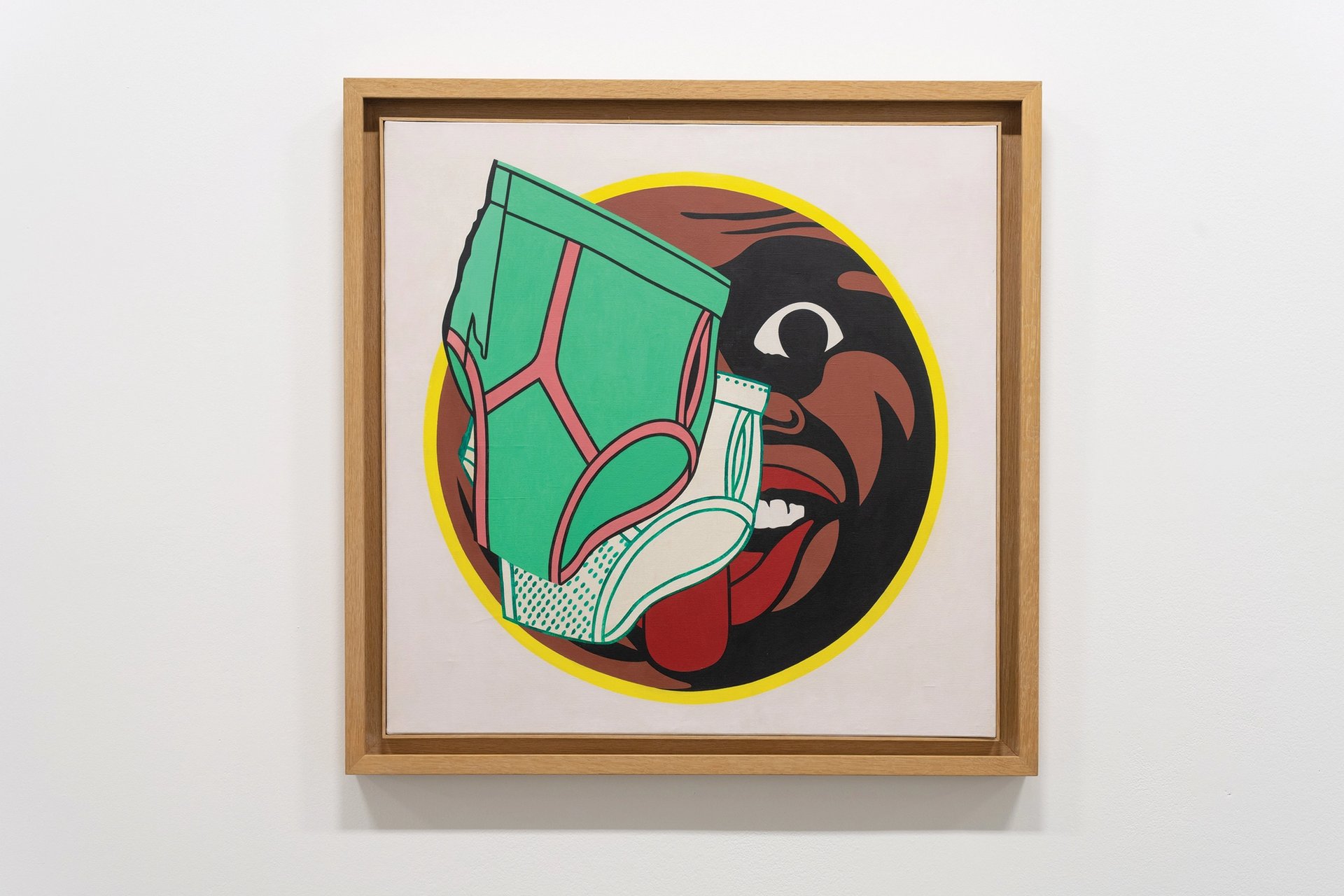

Hervé Télémaque's Convergence (1966) Photo: Musée d'art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Etienne Métropole / Cyrille Cauvet © Hervé Télémaque; ADAGP; Paris and DACS; London 2021

Later, you knew the poet John Ashbery.

I met him around 1961 to 1962. I was quite friendly with him. That’s why he did the preface for my first show in London, at the Hanover Gallery. He played an important role in my life. He thought that I should develop a literary form of painting, properly literary—that I should immerse myself in the literature of Raymond Roussel, of which he was a great fan. He thought that there was potentially in my painting a slant towards literature, a similar sophistication and hermeticism to Roussel.

You left the US because of the racism there—it effectively forced you to make a decision to move to France.

There is a practical reason also; it was very difficult. As a young man, like everybody in New York at the time I wanted to have a big flat in the lower part of New York. Except for me, being a “negro”, it was too difficult to find one. So for that reason it was important that I had to move to an easier city like Paris.

“I get tired of techniques quite quickly and change them; it is a lazy answer to the problems of painting”

Was your artistic language established in the US and carried over to Paris?

A work in the Serpentine show, L’annonce faite à Marie, painted in 1959 [in the US], was the start of my future development. There were already bits of writing that I was starting to put in. And I still kept an interest in English; however slowly and badly I learnt it, I was learning, and it stayed in my brain. I always say that I am a little Haitian, a little American and a little French, and that therefore I work in this confusing mishmash. It’s the nature of my work.

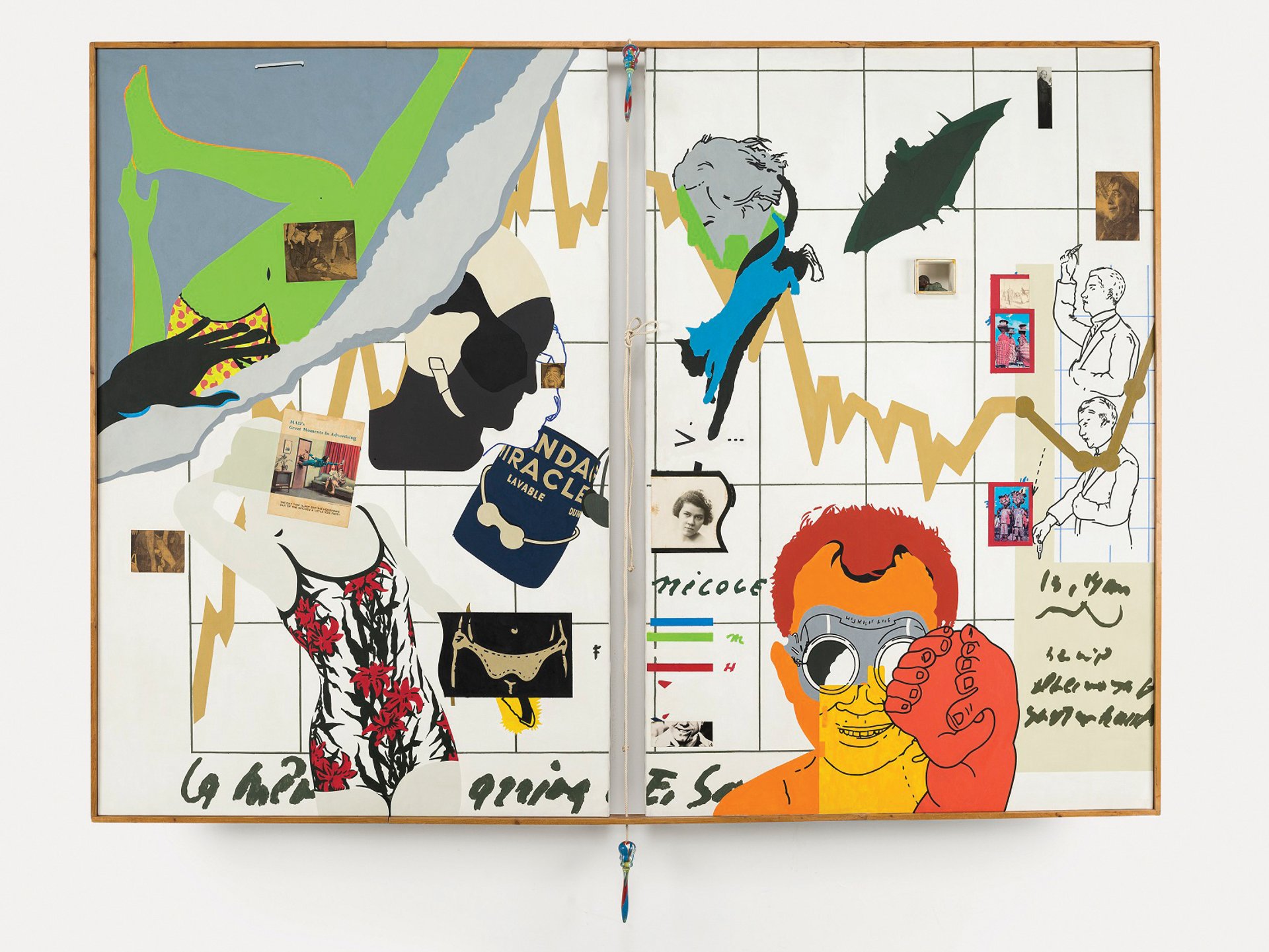

Télémaque’s Serpentine Galleries show includes Fonds d’actualité, no1 (2002), on loan from the Centre Pompidou Photo: Hugo Glendinning; Serpentine Gallery

There was an engagement with Pop Art, but would you describe your work as Pop?

The works I painted between 1962 to 1966 are quite Pop, yes—not technically but intellectually Pop. And in fact my method, even now, remains fundamentally Pop.

Do you see your work as having a strong relationship to collage?

That happened later, in the 1970s. After oil painting, I switched to acrylics and then, at one point, I just did paper collages for several years. I moved on to drawing, to objects as well. I get tired of techniques quite quickly and change them; it is a lazy answer to the problems of painting. The first series of collages was in 1973. Maël, my wife, was a very great seamstress and I adopted a technique that comes from sewing, namely that you make a pattern to then cut out shapes. [This is a] specifically feminine technique that I stole from my wife to such an extent that when I wanted her at one point to make work with me, she didn’t have my dexterity with scissors.

You are associated with the Narrative Figuration movement.

I really liked my great New York forebears—Franz Kline, De Kooning and so on. But while I really appreciated their work, there was also an academic moment in that epoque—all of New York, around 1957 to 1961, was invaded by Abstract Expressionism and would slip into decoration. It was a phenomenon that one found in all the New York galleries, which was exhausting and very negative, in my view. That’s why I turned to my personal life and found that I could, through narrating my life, enrich the pictorial situation of the time. That brought me to Narrative Figuration in Paris, where I continued in the same direction.

Hervé Télémaque's Petit célibataire un peu nègre et assez joyeux (1965) at Serpentine Gallery Photo: Hugo Glendinning

To what extent did you feel you needed to address social issues in your work, like in the Banania series, which dealt with racism?

It happened naturally in my work. It was difficult, in the context of the time, to escape racial problems, and in Paris I found basically all the elements that had already bothered me in the US. It is the same: it is the colonisation common to the US and France. I myself am a product of French colonialism in Haiti, which at the time was called Saint-Domingue. And so, it was natural that it fed into my thinking. And it’s still going on. Look at what is happening in France today.

I want to talk about another influence, Hergé, and the cartoonish aspect of your work. To what extent was it homage and to what extent was it a critical engagement?

There was nothing critical about it. I was impressed by the speed of his style which, for me, would help me to tell my stories. I hijacked Hergé for personal gain, but out of serious admiration. I knew him, by the way. And I can tell you a funny story: he came to see me when I was in a studio in the 19th arrondissement [in Paris] and I was terrified that he was going to come and reproach me for using his work dishonestly in my paintings. In fact, he had come to commission a work from me. That changed our relationship altogether. I painted one painting for him and he was happy with it.

Are there new or recent works in the Serpentine exhibition?

Only one. I’m retired; you know how much importance the French attach to retirement! I am 83 years old. But I still want to work for a few years. You will be able to see one big ten-metre painting that I painted recently in my studio in Normandy. And I have a few paintings that I’ve started that I want to finish, but not too many. When painters are old, they do the worst painting of their lives, so I am not sure I want to be a part of this!