Like many women of her generation, Judy Chicago had to fight for her rights and for a modicum of the attention that accrued to far less talented men. And from time to time—starting, perhaps, with that famous 1970 photograph showing her in the corner of a boxing ring, gloves on—she has played with her own reputation for being a fighter.

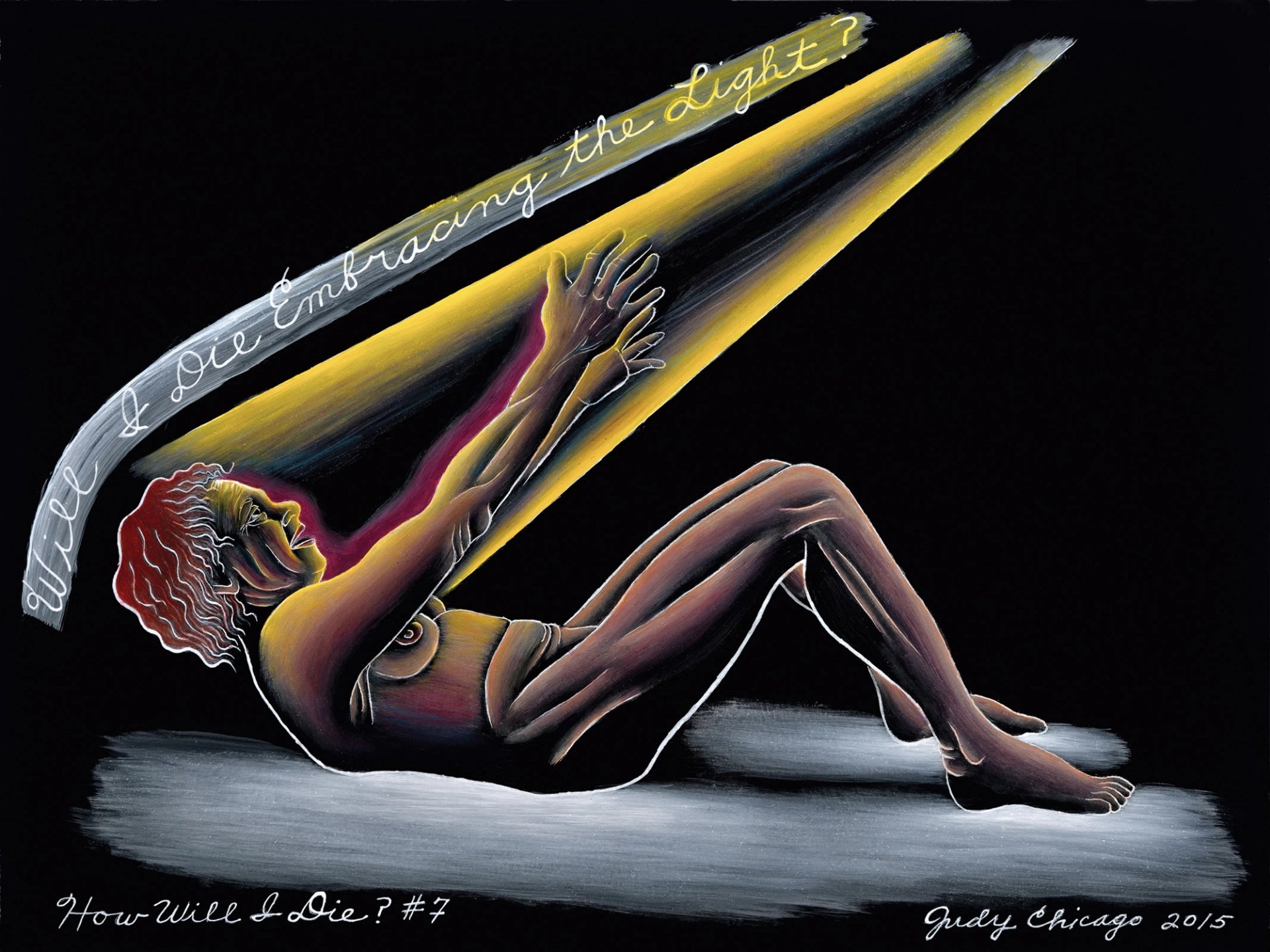

Her exhibition at the de Young Museum, billed as her first retrospective, is confrontational in another way. Right away at the entrance you encounter powerful images that the artist, 82, recently made in attempts to envision her own death. On the opposite wall are bleak pictures she made of animals nearing extinction, from sea turtles to elephants, accompanied by her precise descriptions of how people are inadvertently or intentionally killing them. Most of the images are small but mesmerising, done in kiln-fired glass paint on black glass that reflects your own image as well. Welcome to the end of the world, and you are implicated.

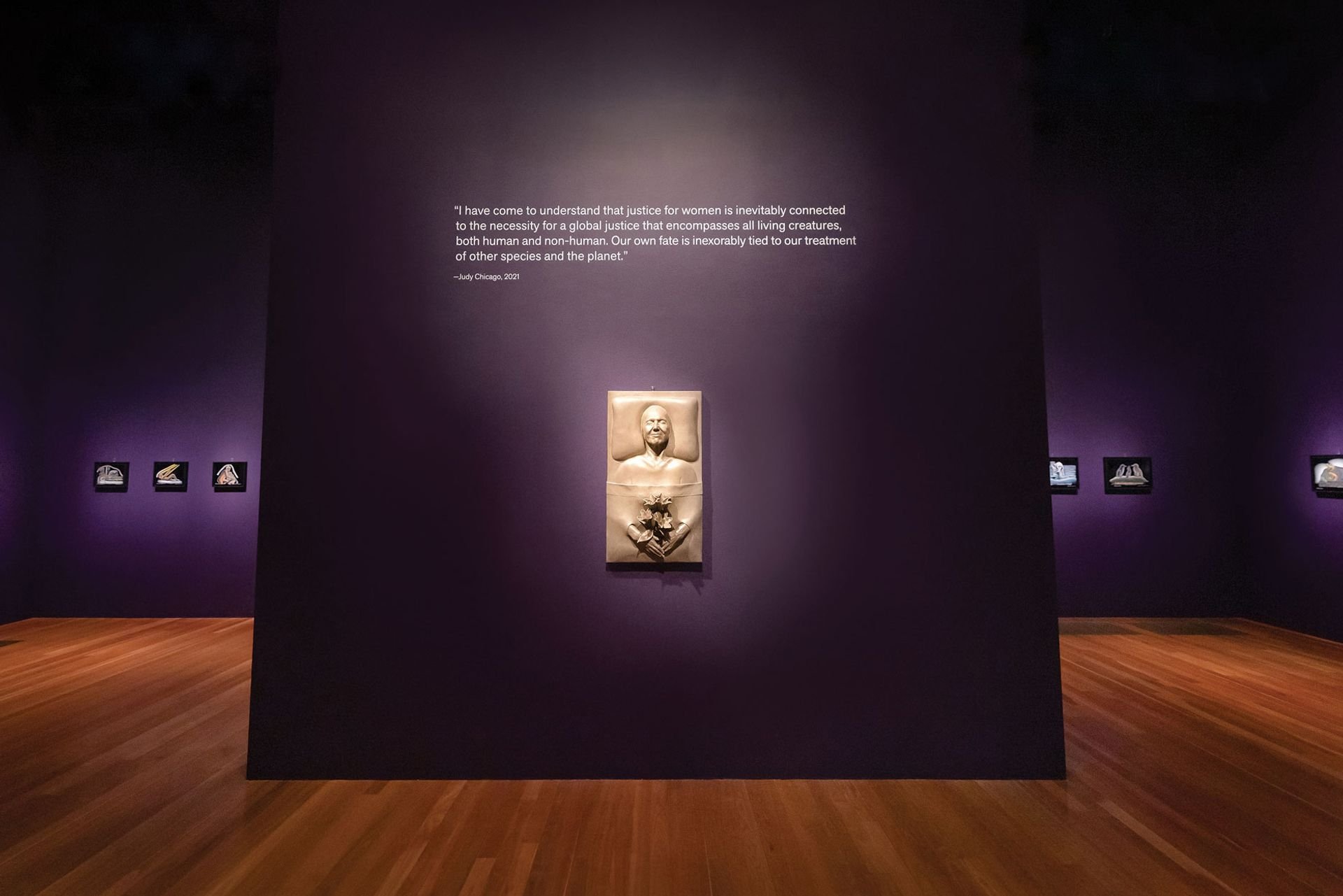

Judy Chicago’s first retrospective includes self-portrait Mortality Relief (2016), part of her recent project The End: a Meditation on Death and Extinction (2012-18) Photo: Gary Sexton; Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS 2021

Chicago made this series, The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, from 2012 to 2018, and in a brilliant move by Chicago and curator Claudia Schmuckli, the show unfolds in reverse chronological order from there, moving to her 1990s work on the Holocaust, leading to her 1980s Birth Project and then culminating in the work from the 1960s and 1970s that made her such a central figure in Post-Minimalism and the feminist art movement. (Also astute, since Chicago is famous for her use of colour: painting the entrance in Benjamin Moore’s Exotic Purple.)

Installation view of Judy Chicago: A Retrospective at the de Young Museum Photo: Gary Sexton. Judy Chicago / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS 2021

Flipping the script chronologically forces us to confront Chicago’s work from the last few decades, which art critics have been quick to dismiss and which fans of her early feminist work might not even know. One common complaint is that the more recent work seems too raw or emotional. But isn’t that often an expedient way to dismiss women? And some say that her imagery verges on cartoony. True, but so does much important Black portraiture being made today, not to mention the history of the Mexican and Chicano mural movements, which broadly speaking share Chicago’s underlying goal of accessibility and legibility.

I still find parts of the Holocaust Project (1985-93) frustrating and even a bit over-clever, like the two-faced format of the 1993 Four Questions paintings where you see different images depending on where you stand. But the more you look at Chicago’s recent work, the more you begin to clear the jungle of prejudice that surrounds it. And The End especially, which nods to and compares to Käthe Kollwitz in its deep excavation of grief, stands as some of her most honest and provocative image-making.

It also makes a great pairing with another standout in the show, Birth Project (1980-85). For this work, Chicago developed stylised imagery of women giving birth—a very rare subject in art at the time, with a particular focus on the painful-powerful moments of the baby crowning. The works in this gallery offer creation myths of different orders: the universe giving birth to the Earth, the Earth giving birth to various life forms and women in labour, amid energy fields that look like fuller versions of Keith Haring’s graphic slashes and ripples. Most spectacular is the 32ft long Prismacolor-on-paper drawing called In the Beginning (1982), which puts different genesis stories into play by pairing undulating, female imagery and short, incantatory texts in Chicago’s expressive, looping handwriting, all set against a black background pointing to the original void.

Installation view of Judy Chicago: A Retrospective at the de Young Museum Photo: Gary Sexton. Judy Chicago / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS 2021

I especially liked the way this gallery brings together many long-running themes in Chicago’s art, from what she calls “core” female imagery (think labial or vaginal openings, the sort of flowering that puts her in visual dialogue with Georgia O’Keeffe) to her integration of writing into image-making. Plus, Birth Project, for which she worked with over 150 needleworkers, is a great example of the artist embracing different media, including those marginalised as “craft”. This one room alone contains examples of ink drawings, the Prismacolor-on-paper sketches, sprayed and stitched fabric, a modified Aubusson tapestry, crochet, needlework and embroidery, plus small ceramic “goddess” figurines she made in homage to prehistoric sculptures.

Not present here is oil on canvas: a medium of little interest to an artist who has long set out to fuse colour and form and challenge the traditional, patriarchal version of art history.

A seat at the table

Some of her most important work in this direction is on display in the next gallery, devoted to the creation of The Dinner Party, the landmark feminist installation that gave 39 historically important women a seat at the table with china-painted plates she made in their honour. Unable to borrow the work itself, now permanently installed at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the de Young is showing instead several sketches for it, a number of early china-painted porcelain test plates (including interesting variations on Virginia Woolf’s plate) and a video tour of the work in situ.

Schmuckli’s wall labels in this section are remarkably direct, both crediting the project for combating “the systemic erasure of women’s achievements from the historical record” and criticising it for perpetuating the erasure of women of colour. She describes the bizarre treatment of the one Black woman at the table, Sojourner Truth, who, as Alice Walker once pointed out, is represented on a plate with three faces instead of Chicago’s usual sexual imagery, and lets Chicago briefly address the issue. (Schmuckli relays that Chicago didn’t want to eroticise a black woman.) It is one of the most surprising moments in the show. Instead of ducking from controversy by excluding a work or banishing the criticism, the curator has started a conversation about race and sexuality.

One of Chicago's more recent works from her series addressing mortality, How Will I Die? #7 (2015) Judy Chicago/ rtists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS 2021

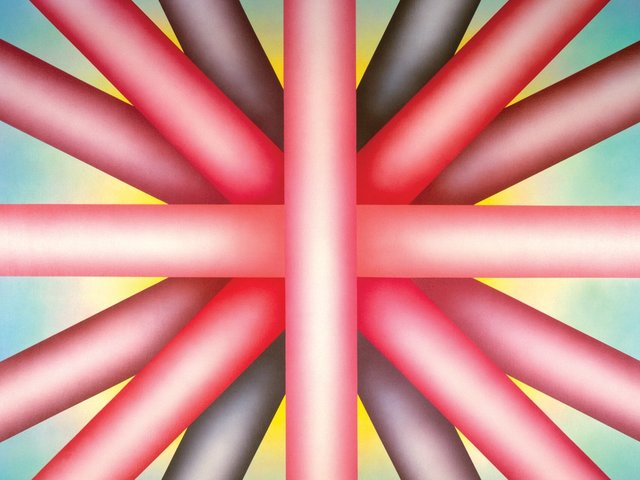

The final room in the show, dominated by Chicago’s early minimal work from the 1960s and 1970s, is glossy and gorgeous. It includes four examples of her candy-coloured acrylic-on-acrylic Pasadena Lifesavers paintings from 1969 and 1970, her maxi-coloured Minimalist sculpture Rainbow Pickett (1965, recreated 2021), and her vibrant, some would say garish, paintings on car bonnets from the same year. Inspired by the macho Finish Fetish movement of Southern California, Chicago famously attended autobody school and learned spray-painting techniques to make the car bonnets. But they were maligned at the time as too feminine in colour and form. Here, the show arrives at the generative moment where Chicago begins to visibly reject and reform the conventions of male-dominated art history.

The only thing that seems to me missing from the show is her messier, more performance-oriented feminism of the 1970s, like her tampon-littered Menstruation Bathroom and the hilarious, sing-song Cock and Cunt Play, which helped to make Womanhouse, the short-lived Los Angeles performance-exhibition space from 1972, so memorable. The inclusion of two 1971 photographs and Johanna Demetrakas’s video about Womanhouse, which plays on a small screen with subtitles and no sound, is not enough to convey the radical nature of this intense collaboration, alternative education and consciousness-raising that Chicago helped to inaugurate through the Feminist Art Program she founded in Fresno, the one she ran at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) with Miriam Schapiro (which gave rise to Womanhouse), and the Woman’s Building that she later helped to establish.

The omission is not entirely surprising. In trying to organise an accessible exhibition, it’s natural for a curator to focus more on a subject’s large, polished art objects than on her experimental and often ephemeral contributions to a group environment. Tampons are hardly archival. And museums everywhere assume that making art is more important than making artists. But the creation of Womanhouse in particular was so important that Gloria Steinem has said she could divide her life into before and after she saw it. Could it be time for a recreation?

• Jori Finkel is a regular contributor to The Art Newspaper and the New York Times

• Judy Chicago: In the Making, De Young Museum, San Francisco, until 9 January 2022. Curator: Claudia Schmuckli, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco