Among the highlights of the Kunstmuseum Basel is Van Gogh’s Marguerite Gachet at the Piano (1890), depicting the daughter of the doctor who treated the artist after he had shot himself. But what is the story behind this intriguing portrait? And why did Dr Paul Gachet allow the young woman to pose for Vincent?

While researching my latest book, Van Gogh’s Finale, I was struck by the importance of the role played by Dr Gachet, who lived in Auvers-sur-Oise—a village north of Paris. The critic Georges Rivière described the doctor as “certainly one of the most curious personalities of the 19th century”. Gachet’s artistic friends reputedly regarded him as a skilled doctor and an amateur artist; his medical colleagues saw him as a talented artist and a mediocre doctor.

Although the doctor began by keeping a physician’s eye on Vincent on his arrival from the asylum in May 1890, the two men quickly became good friends. Dr Gachet invited Vincent for Sunday lunch on 22 June to celebrate the joint birthdays of his two children, Paul and Marguerite, who had turned 17 and 21 the previous day. Over a convivial meal Vincent asked again if Marguerite would pose for him. It was quickly agreed and the portrait was completed that very week.

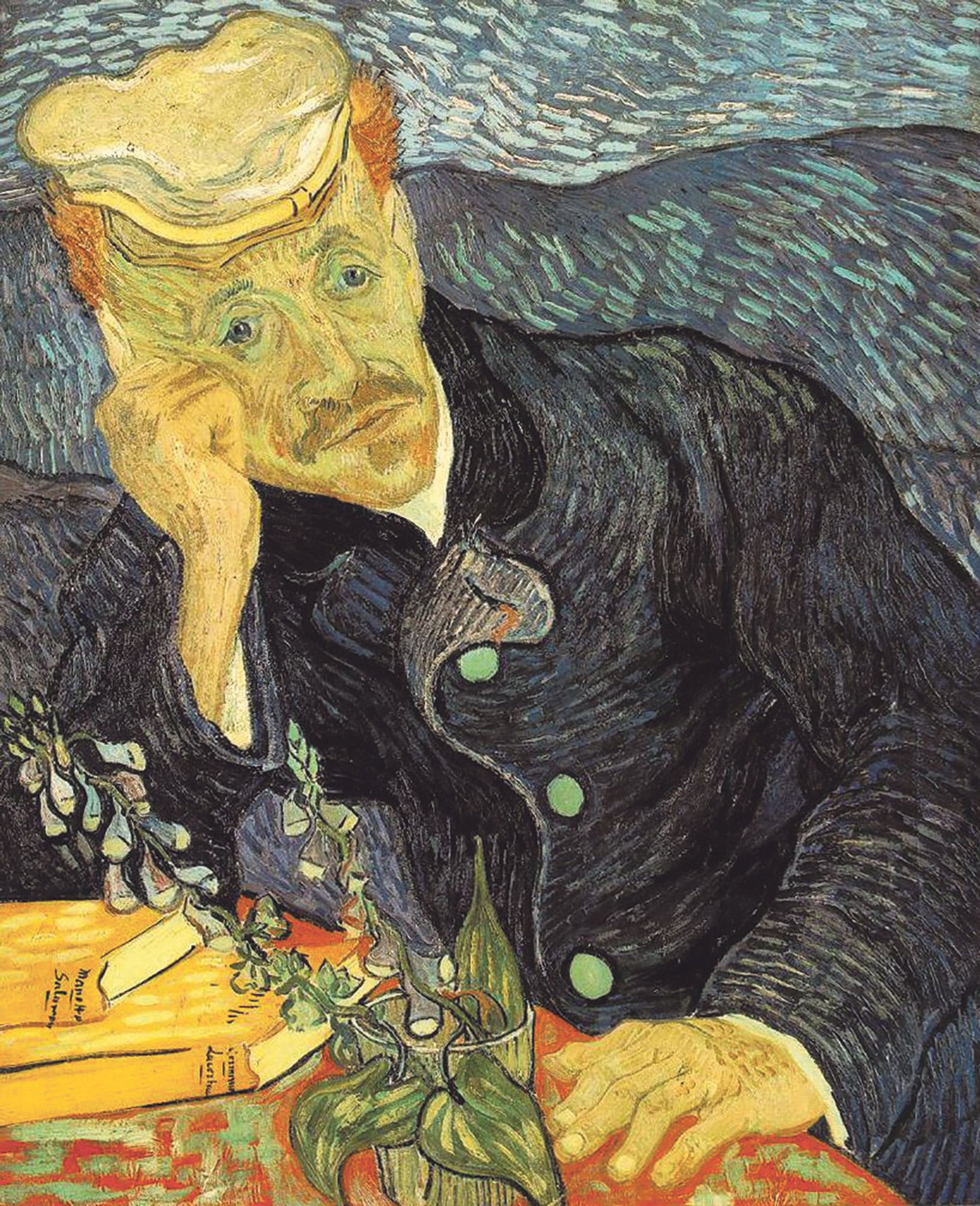

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (June 1890), first version, now in a private collection Private collection

It was probably Dr Gachet’s idea that his daughter should be depicted at the piano. In 1873 he had made an etching of his wife Blanche playing at the keyboard. Blanche had been a talented musician and after her death in 1875 the piano remained in the salon of their Auvers home—and their daughter Marguerite continued the family’s musical tradition. Dr Gachet himself loved music, and he once composed a piece he dedicated to one of his favourite black cats.

Vincent described the painting to his brother Theo: “I painted Miss Gachet’s portrait, which you’ll see soon, I hope. The dress is pink. The wall in the background green with orange spots, the carpet red with green spots, the piano dark violet. It’s one metre high and 50 wide. It’s a figure I enjoyed painting—but it’s difficult.”

Marguerite Gachet at the Piano was painted on a “double-square” canvas that was an unusually narrow format for a portrait. Van Gogh began with a preliminary drawing, which still survives. A minute speck of green pigment on it suggests that the sketch was close at hand while he was working on the painting.

Van Gogh’s Marguerite Gachet at the Piano (June 1890) Photo: Martin P. Bühler; Kunstmuseum Basel

The doctor’s son, also named Paul, later recorded that it had been completed in just two days: “Standing at his easel, Vincent stepped back, advanced, moved away, approached, stooped, one knee on the ground, rose, bowed almost without stopping.” Vincent had forgotten to bring his palette, so the doctor lent him one of his. This paint-splattered relic was preserved and in 1951 it was donated to the Louvre.

Rumours of love

Marguerite’s over-elongated fingers strike the keys as she concentrates on the music (Van Gogh was never very good at painting hands). It is not so much a portrait of her as an individual, more a timeless depiction of a musician engrossed in a melody.

Although this may come as a surprise, it has been suggested that Marguerite had romantic feelings for Vincent. This idea was published by the distinguished Van Gogh specialist Marc Tralbaut, who in 1969 described it as “an old rumour”. He quoted Madame Liberge, a local woman who said that the doctor’s daughter “never admitted that she had fallen in love with the painter”, but “her whole attitude and everything she told me betrayed her true feelings”.

This represents flimsy evidence of a thwarted affair and it seems unlikely that the young Marguerite would have been attracted to a socially awkward 37-year-old man who had mutilated his ear and had just arrived from a mental asylum. In addition, Dr Gachet surely would not have allowed his daughter to model if Vincent had appeared to harbour any special feelings for her.

“It is not so much a portrait of her as an individual, more a timless depiction of a musician engrossed in a melody”

Although Vincent normally gave his paintings to Theo (who supported him financially), he sometimes presented portraits to sitters—and this one was given to Marguerite. She later had it in her bedroom, displayed in a plain white frame and hung between two large Japanese prints of female figures by Keisai Eisen. Marguerite went on to live a reclusive existence, never marrying and remaining in the family home, along with her brother Paul Jr and his wife.

In 1934 Marguerite sold this very personal painting, which had never left the house in more than 40 years. The Gachet siblings had dozens of other valuable works by Van Gogh and Cézanne, so it was a curious choice to sell. The buyer was the Kunstmuseum Basel, which paid 315,000 French francs.

Faded beauty

Van Gogh’s pigments have often deteriorated with age and Marguerite Gachet at the Piano is no exception. His reds are particularly vulnerable and the young woman’s original pinky dress eventually faded to a bluish and purplish white.

Marguerite’s actual piano still survives, now in the Musée des Instruments de Musique in Brussels. It was given to the museum in 1952, the year of her death, but since then it never seems to have been exhibited. When I once saw the Alphonse Juvenois piano in storage, it had sadly lost its two candelabras, but after I showed the curator a reproduction of the Basel painting they were discovered in another part of the store.

The Basel painting and the Brussels piano have never been together for nearly a century, so it would be wonderful to temporarily reunite them for a display. In the meantime, visitors to Basel should seize the opportunity to see this striking portrait.

• Van Gogh’s Finale. Auvers & the Artist’s Rise to Fame, Martin Bailey, Frances Lincoln, London, 240pp, £25 (hb)

• Bailey is a long-standing correspondent for The Art Newspaper and also writes a weekly blog, Adventures with Van Gogh