This July marks the tenth anniversary of the UK government’s e-petitions, a system whereby online campaigns backed by 100,000 signatures are automatically considered for debate in the UK Parliament. Since its introduction, 169 petitions concerned with art have been instigated.

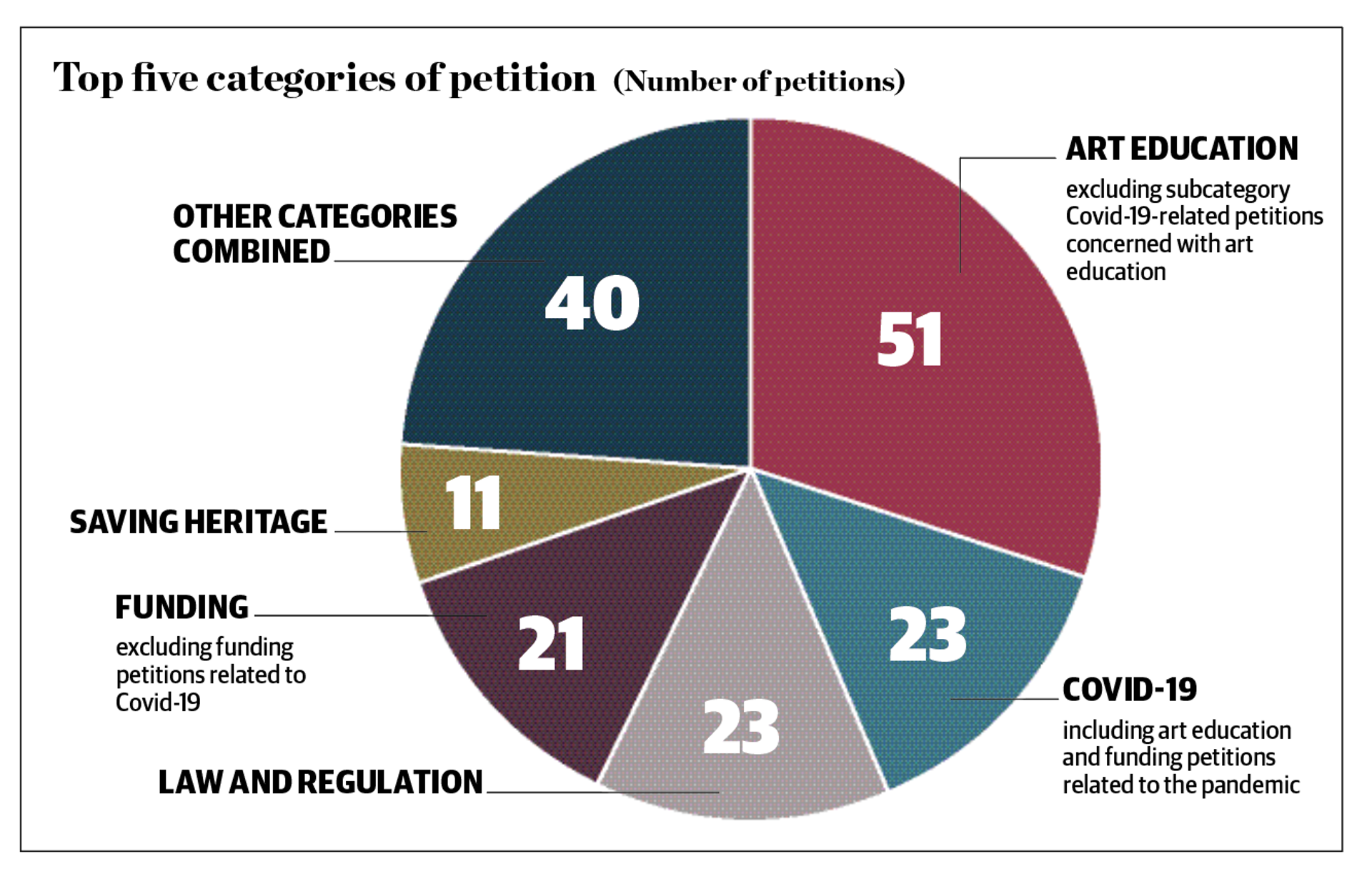

So, what has been riling the art-loving public? Seemingly, education—or, rather, the lack of importance given to it. Around a third of arts-related petitions were concerned with the issue, with many stressing the importance of keeping a range of creative subjects within the core curriculum and others calling for greater financial support for students undertaking creative subjects.

“By not investing in arts education, you are not investing in the future of arts, and for many, this is not reflective of a society that they envisaged,” says Paula Orrell, the director of the Contemporary Visual Arts Network. “There is no wonder therefore that arts education has been a recurring concern for the British public for the past ten years, and if the balance is not addressed, it will continue to be a concern for many years to come.”

The Art Newspaper’s analysis comes after an open letter from major cultural players earlier this year, called on the government to drop its plans to cut higher education funding for “non-strategic” subjects (including the arts) by 50%. Despite an e-petition on the subject attracting more than 36,000 signatures, the government moved ahead with the cut last week.

However, only three of the 169 arts-related petitions crossed the threshold for triggering a parliamentary debate, so success rates are seemingly low. Around 70% of all e-petitions are rejected, primarily due to duplication but also where the subject matter is considered to sit outside the government’s jurisdiction. Some of the more obscure include a call for all politicians to “wear mandatory hats” as it would “show their importance” (submitted in October 2020), making the date of the Eurovision Song Contest final a national holiday (2018) and a request for Banksy to carry the Olympic Torch (2011).

Among the more obscure petitions is a request for Banksy to carry the Olympic Torch

“The threshold for the [House of Commons Petitions] Committee taking action is high, the threshold for a Westminster Hall debate is very high. This is most definitely a barrier but conversely the Committee has limited time and resources,” says the former director of digital democracy at the Hansard Society and founder of the consultancy FutureDigital, Andy Williamson. He adds that, while other institutions use a more qualitative assessment of the petition (such as the Welsh Senedd, which has a lower threshold, and whose staff advise on the wording of petitions), the Westminster model favours “popular (and populist) subjects over more niche ones that might actually be more important or valuable to take forward.”

© The Art Newspaper

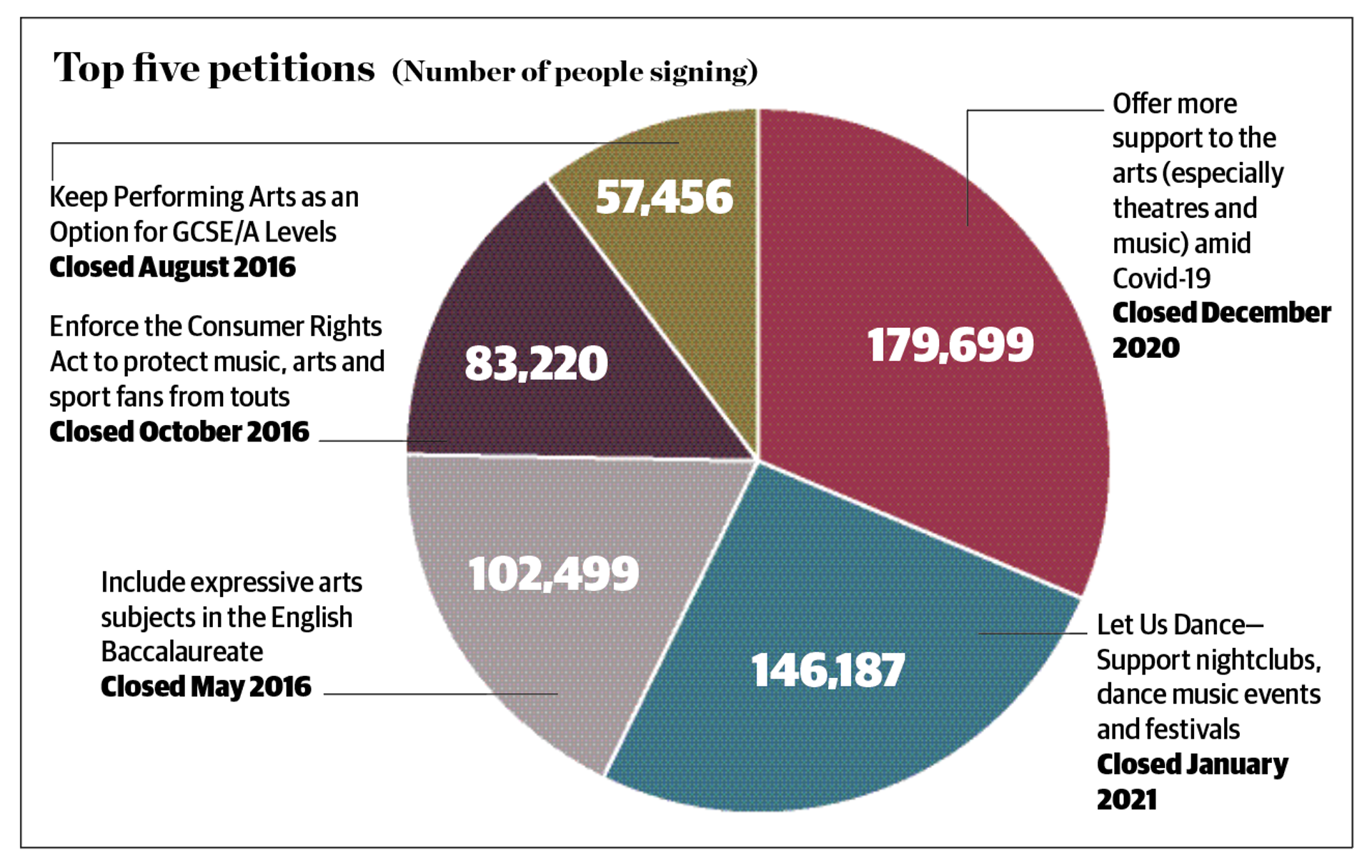

The e-petitions making it into parliamentary debate were dominated by the pandemic, including a recent petition to provide support to the arts (particularly theatres and music) amid the Covid-19 outbreak and another to support music events and festivals. In these cases, the government reiterated its support packages for the sector already announced, and made no policy changes. The third petition to reach the threshold was a 2016 outcry over the exclusion of the arts in the English Baccalaureate scheme.

Arguably, e-petitions raise awareness, regardless of their outcome, and many of the issues raised in them will be familiar to the art world: legal issues such as a push to ban the trade in ivory, calls for VAT reductions, and numerous calls for greater funding.

Concerns were both national and local, particularly regarding heritage, with demands for regional culture to be better protected sitting alongside very local ones, such as the 521-strong petition to prevent Fanshawe Community Hall in Dagenham, London, from being closed for housing developments.

© The Art Newspaper

Even though most e-petitions are rejected, all are available to be viewed online, in keeping with the system’s original goal to create a “more accessible and transparent” parliament, as outlined by Commons leader George Young when announcing its launch, in July 2011.

Williamson concludes that the future of e-petitions and their role in shaping democratic discussion is “difficult to know; democracy moves perhaps a step or two behind the direction of travel in society and the negativity around social media and disinformation is not helping entrench digital solutions”. The future of the issues raised in the art sector is, perhaps, equally foggy but the data is clear: the UK public cares about art.

The experience of one e-petitioner

English Baccalaureate petition being debated © Crown copyright

When Essex-based drama teacher Richard Wilson read an article about a number of school subjects (including GCSE Drama) about to be abolished in 2016, his heart “dropped”.

Fast forward half a year and an e-petition he created, calling for expressive arts to be included in the English Baccalaureate system, had garnered 102,499 signatures and the issue was scheduled to be discussed in the House of Commons.

“I was delighted to see it take off. It got an early boost, from Billy Bragg, who shared it and helped it tip over the 10,000 mark,” Wilson says. The e-petition directly addressed the then-secretary of state for education, Nicky Morgan, and stated that “it is wrong to say that the arts are not worthy of inclusion in a measure used to grade a school’s success”.

The subsequent parliamentary debate, in July 2016, failed to see a U-turn on the government’s position, but Wilson encourages others to step forward with their issues: “It is one of the most productive ways to get an issue in the public eye. My anti-Ebacc petition was, frankly, an issue which was difficult to communicate to the wider electorate, even though it affected every family in England with a school-age child.”

Doing the numbers

The data was taken from the UK Parliament website, and includes current petitions and archived petitions to previous governments (both excluding the “rejected petition” data), broken into the following data brackets: 2010 to 2015; 2015 to 2017; 2017 to 2019 (all closed, as petitions are kept open for signatures for six months only); and current.

The full data set consisted of 239 petitions featuring the term “art”. We did not include petitions that were rejected (for example, if they were not to be within government’s jurisdiction or covered by another petition) and petitions where we deemed the term “art” not relevant (mostly those using the term “state-of-the-art”) .

We looked at each of the petitions in our dataset, and organised them into categories, as in the charts.