The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is famous for bestowing generous no-strings-attached grants, commonly known as “genius” awards, on individuals of exceptional creativity. Now, 29 of the more than 100 recipients in the visual arts field over the last four decades are participating in a sprawling, collaborative biennial- style exhibition in Chicago that rolls out at 19 venues this summer.

Drawing heavyweights from the foundation’s roster of fellows, including Kerry James Marshall, Julie Mehretu, Mark Bradford, Kara Walker and Carrie Mae Weems, the exhibition Toward Common Cause: Art, Social Change, and the MacArthur Fellows Program at 40 has been organised by the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago.

Don Meyer, a senior programme officer in the fellows programme at the Chicago-based MacArthur Foundation, which uses outside nominators, evaluators and selectors in its secretive grant process, says: “We wanted the show to connect meaningfully to a broad notion of social change.” To that end, the foundation approached the curator Abigail Winograd three years ago to conceptualise the 40th-anniversary exhibition.

“When given the opportunity to pick and choose from this list of artists, my immediate answer was yes,” says Winograd, who partnered with the Smart for its community engagement and academic resources.

MacArthur award-winner Nicole Eisenman's The Triumph of Poverty (2009) Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles

Winograd is using the idea of “the commons”—how air, land, water and culture can be held in common yet not necessarily be freely accessible—as an organising principle to consider questions of inclusion, exclusion, ownership and access, and how artists can contribute speculative solutions to larger social issues. She looked for inspiration to the group of “genius” fellows, not one of whom turned her down (an indication of the transformative power of the MacArthur award on an artist’s work and career). More than half are showing new work, including nine community-based commissions by artists such as Fazal Sheikh, Wendy Ewald and Amalia Mesa-Bains.

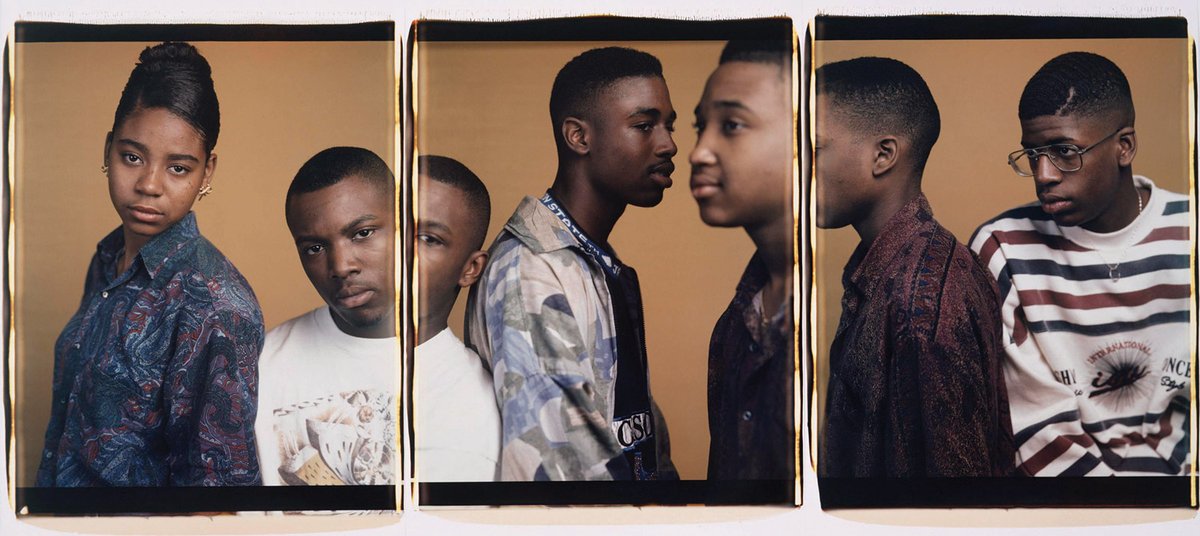

A large group show opening on 15 July at the Smart focuses on environmental justice and the disproportionate burdens borne by communities of colour through works by Jeffrey Gibson, Alfredo Jaar, Xu Bing, Toba Khedoori and LaToya Ruby Frazier, among others. At the nearby Stony Island Arts Bank, another group show will include works by Fred Wilson, Trevor Paglen, Nicole Eisenman, Deb Willis and Dawoud Bey that explore identity and representation—“how we see or don’t see each other because of race or gender or class”, Winograd says.

Many artists are showing in more than one venue. Rick Lowe’s project Black Wall Street Journey, for example, uses television monitors installed in the Smart Museum, the window of the student centre at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a storefront on the city’s South Side to pump out information about the heroic efforts of African Americans to find economic stability and shift the narrative about Black people. “Each component is coherent, but they do point to each other, so we can try and move people across the city to see different pieces of the exhibition,” Winograd says.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby has collaborated with the Chicago Housing Authority and the Smart’s programme for teenagers to transform her paintings into four mural-like banners displayed on building exteriors—two at the National Public Housing Museum and two at the Minnie Riperton Apartments in Fuller Park, on the South Side. At the Riperton Apartments, residents were asked to vote for their favourites among Crosby’s images evoking family life and domestic love, which were then sized to the buildings in banners some 40ft high, one of which is visible on the major thoroughfare.

“It was important for Njideka to have her work seen by an audience that may not feel comfortable in a museum setting,” Winograd says.

Both Mel Chin and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle are part of the presentation at the Smart and have new commissions at the Sweet Water Foundation that recovers land and housing in the under-served South Side neighbourhood of Englewood. There, in Sweet Water’s urban farm, Manglano-Ovalle has installed a functioning well that simultaneously draws potable water and serves as a public sculpture to highlight the subject of water access and issues of equity. For the Smart, he has designed and built a large meeting table in the atrium where people can pump water from one of its four legs as a kind of doppelganger well. “Both are a platform for action, for performance, for discourse,” Manglano-Ovalle says.

The first artists in Toward Common Cause to have been awarded a MacArthur were David Hammons and Guillermo Gómez-Peña, who each received the grant in 1991, a decade after the programme began. Meyer feels that a gradual increase in visual artists among the recipients is part of a broad cultural trend. “Because our process is always reaching out beyond the foundation into the world, nominations reflect what people see as really pressing issues of the day,” he says. “Visual arts have become a piece of the fellowship in a way that they had not been in the early years.”