This weekend venues across London will play host to cutting-edge performance work by artists such as Abbas Zahedi and Darren Bader. And crucially, all of it is for sale. But as any dealer knows, it can be tough convincing someone to pay for something they cannot hold or hang on a wall.

Such is the task of Performance Exchange, a live art programme that holds its inaugural event from 9-11 July in collaboration with ten commercial galleries, including Goodman, Sadie Coles HQ and Kate MacGarry. It aims to give collectors a better understanding of owning a performance—rather than just its corresponding video footage, photographs or ephemera—and demystify the process of buying a live work of art.

“What the market supports and what artists make doesn’t particularly match up at the moment,” says Performance Exchange’s founder and curator Rose Lejeune. “This is an intervention. Performance is more than marketing or an entertaining side act—it is a legitimate, collectible art form.”

This proposition is not an easy sell, not least because of the confusion that often surrounds the medium’s purchasing model. “When transacting around an object-based work it’s usually obvious what you’re buying. With performance not always so,” Lejeune says. To ease collectors into the process, Performance Exchange has produced digital documents in collaboration with programme sponsors Art Fund that explicate the exact terms of sale for each of the weekend’s works. These are “blueprints” that detail instructions and conditions for their re-staging, as well as legalities regarding copyright and resale.

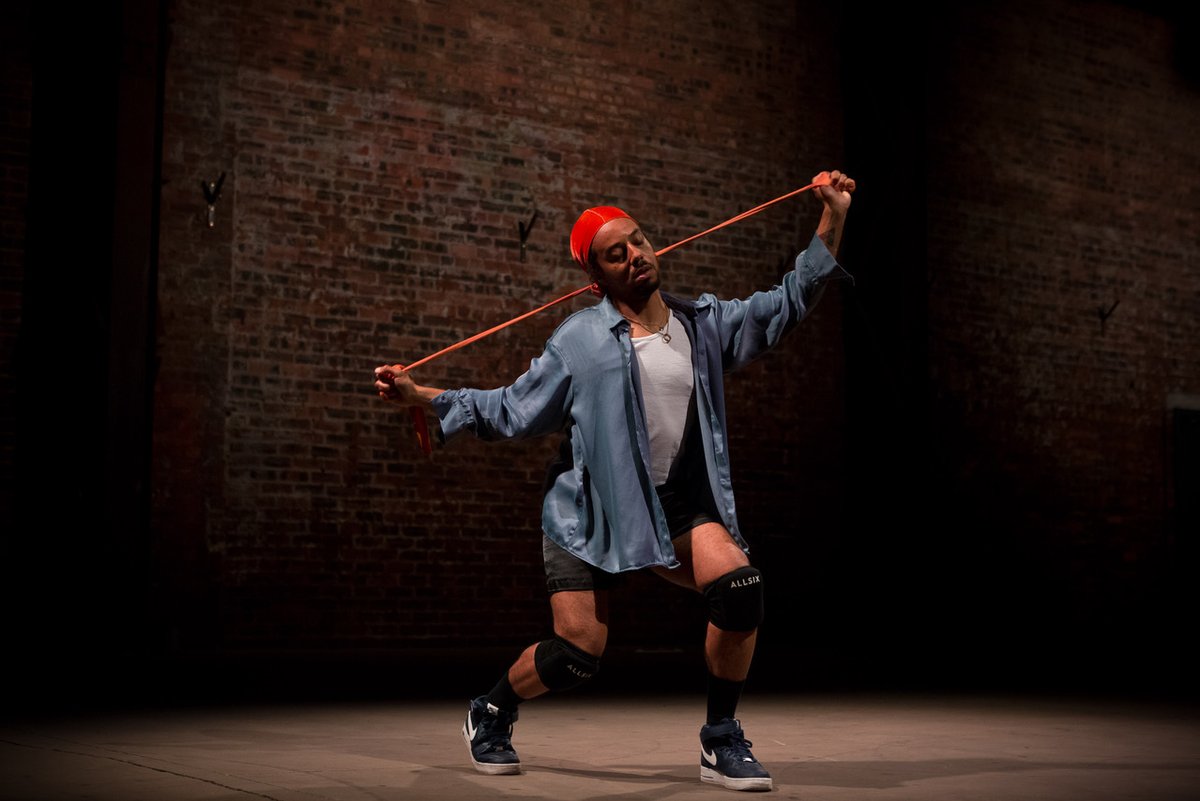

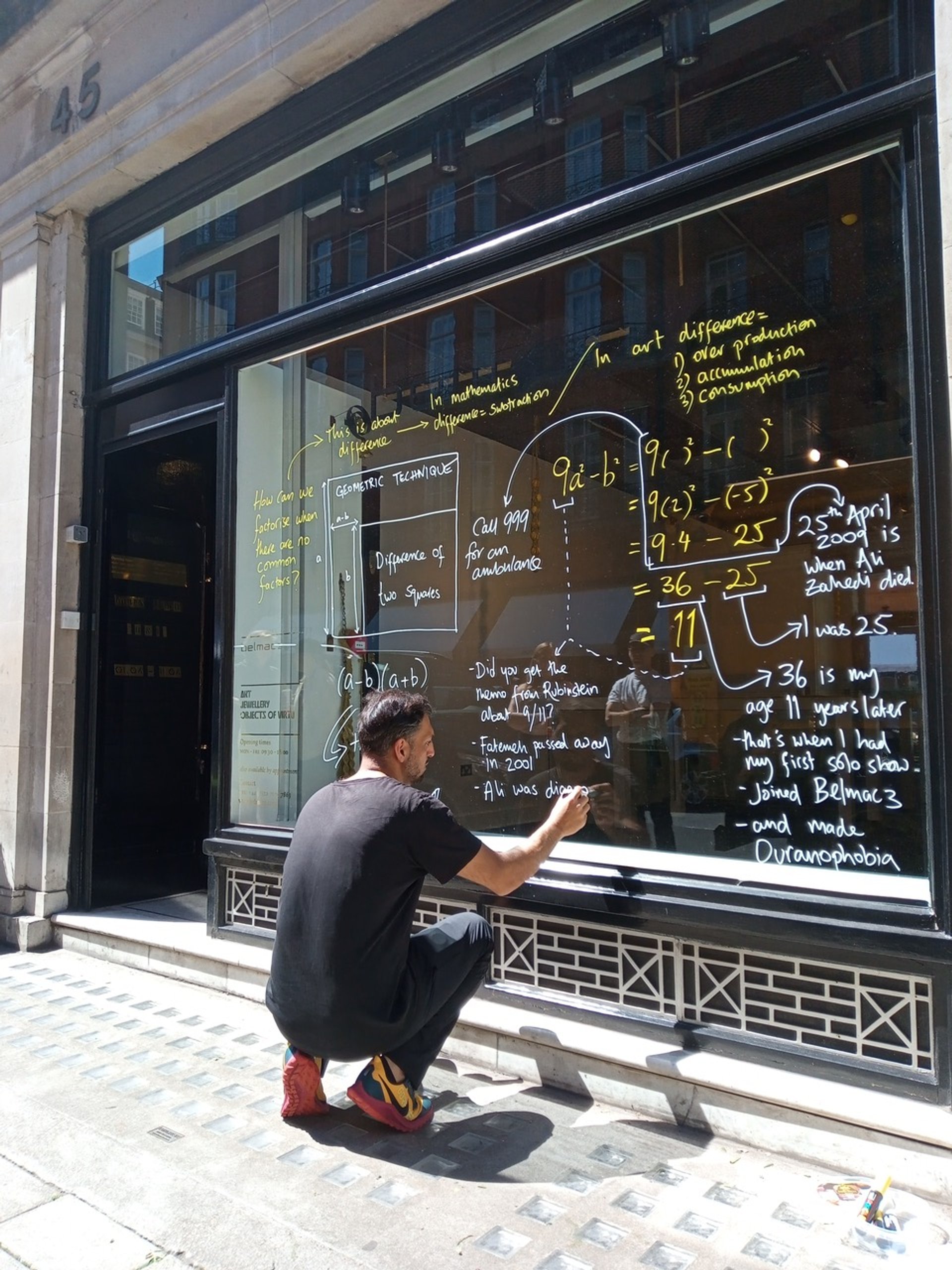

Abbas Zahedi, 11 & 1 (2021). Performance-lecture at Belmacz London Image courtesy Belmacz.

Though based around similar building blocks, these documents are as unique as the works they correspond to and can even add further artistic dimensions to them. With Arcade, Anna Barham will debut a reading performance based on a text adapted from Vilém Flusser’s 1987 scientific treatise Vampyroteuthis Infernalis (vampire squid). Offering the work as an edition of three, Barham instructs all future readers to “re-author the unpunctuated script”. Documentation of each subsequent performance is to be collected in the work’s physical archive (a box included in the sale), ensuring each edition evolves differently over time.

Meanwhile Vitrine will show a newly commissioned durational work by Tim Etchells, whose performances have been collected by Tate. The gallery’s founding director Alys Williams says that a “more transparent structure” to acquire live works is necessary to translate presentation to sales, including in-depth acquisition materials made available in advance of the performance. This weekend will stand testament to what Williams says is a “growing interest in the relevance of contemporary lives, which increasingly value transient experiences over permanent fixtures”.

In recent years, performance has moved firmly into the mainstream, largely thanks to growing acceptance from institutions such as Tate Modern, which hosted Anne Imhof's immersive work Sex (2018) in its underground Tanks, and the Venice Biennale, which awarded its 2019 Golden Lion to the Lithuanian Pavilion's indoor beach opera. And while performance work is by-and-large still bought by institutions that have the resources and space to properly stage them, increasingly private and non-institutional collectors are getting in on the game, aided by commercial ventures such as Frieze Live, launched in 2014, and more recently Brussels-based performance fair A Performance Affair, for which Lejeune is an advisor.

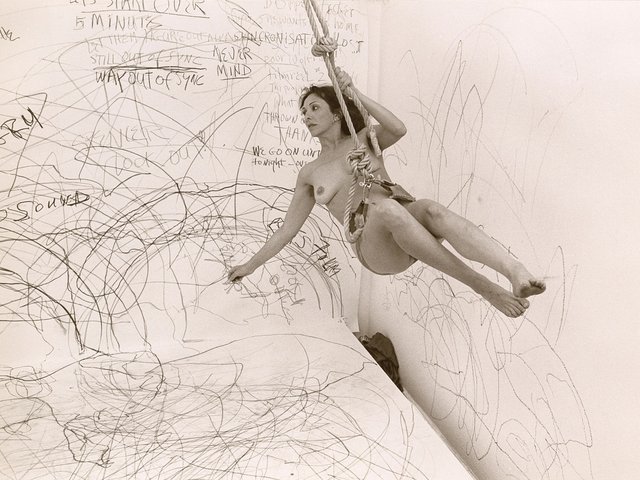

Yet marrying live art to commerce can seem contradictory with the ethos of the fringe, underground work made in the 1970s and 80s, such as happenings on the Chelsea Piers in New York and the nude interventions of the Neo Naturists in London, from which much contemporary performance practice takes its inspiration. But as Lejeune points out, the economic reality those works were created in no longer exists. Rising rents, stagnating wages and funding cuts mean artists can no longer occupy warehouses for pocket change or live in major cities cheaply. Financial stability, while not particularly sexy or avant-garde, is today far more necessary to maintain an art practice.

Having worked in public and live art for two decades, Lejeune considers the beginning of the austerity period in the late 2000s as marking a decline in performance-only practices in the UK. Indeed, at a time when live art proliferates, few artists today tout themselves exclusively as performers, and virtually all incorporate a significant material practice. It is this new generation to whom Lejeune hopes to show that performance can be a secure and serious way to make a living.

Some of this work, at least for now, is still off limits to collectors. “It’s not always suitable or in an artist’s interest to have their performances available for sale,” says Kate MacGarry, who will show a live piece by Turner Prize winner Helen Cammock.

Paul Maheke, who is showing a choreographed dance centring on his personal experience of sexual abuse, says that he has declined several propositions to acquire performance works that he considers "impossible" to collect: "Their nature is very much tied to improvisation and the moment in which they existed. These works live within them and nowhere else,” he says.

In recent months, the conversation around owning intangible art forms has been brought firmly into the public consciousness thanks to NFTs, and many hope to capitalise on this needle shift. "I think that if someone has the insight and will to collect something quite ephemeral like a digital video that will be editioned and probably publicly viewable online, then the step to collect a performance is tantalisingly small," says David Hoyland, founder of Seventeen gallery.

But not all of the weekend's organisers are convinced that the two are so linked. According to the gallerist Sadie Coles it is the "live element" that people have been missing this past year. In fact, although the pandemic hit performance much harder than other art forms, it seems to have also underscored its value, in both the commercial and wider sense. Unique precisely because of its transience, performance art resolutely demands for the viewer to be present in the moment—a state of mind that is increasingly precious and sought after as our existences become evermore mediated via screens. After all, you don’t often realise how good, or valuable, something is until it’s gone.