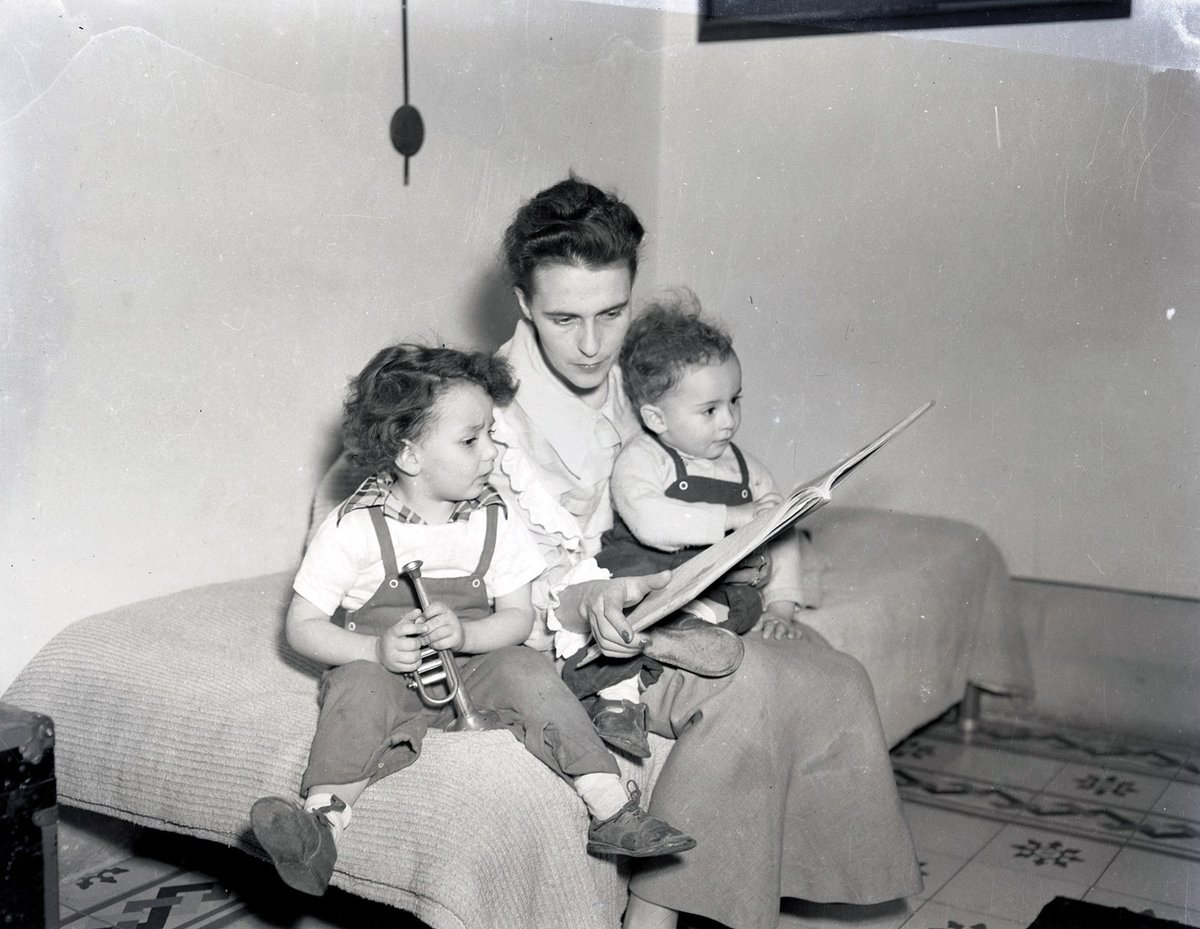

The title for next year’s Venice Biennale, The Milk of Dreams, was inspired by Gabriel Weisz Carrington’s memories of the fantastical bedtime stories his mother shared with him and his brother when they were children. “It was the kind of food you received from your mother, but a mother who could imagine the most incredible things,” he tells The Art Newspaper.

Gabriel’s mother was the British-born Surrealist Leonora Carrington (1917-2011), who moved to Mexico in her 20s. Gabriel remembers as a child sitting with Leonora in a room whose walls were covered with images of wondrous creatures, towering mountains and ferocious vegetation, while she related her wild, funny and outrageous tales of children whose heads become disconnected from their bodies; of Señor Mustache Mustache who had two faces; and of a child called George who liked eating the walls of his room.

Gabriel definitely identifies with the last tale—“the walls had a salty substance that I found very appetising,” he says—and he also remembers a “very sinister” story about a taco-seller in the market who tried to fob kids off with rotten meat. “The thing about my mother was that she had a different attitude from most people towards children,” he says. “She said children had to grow and the only way they could grow was by reading stories, even stories that were sometimes quite horrific.”

A magical world

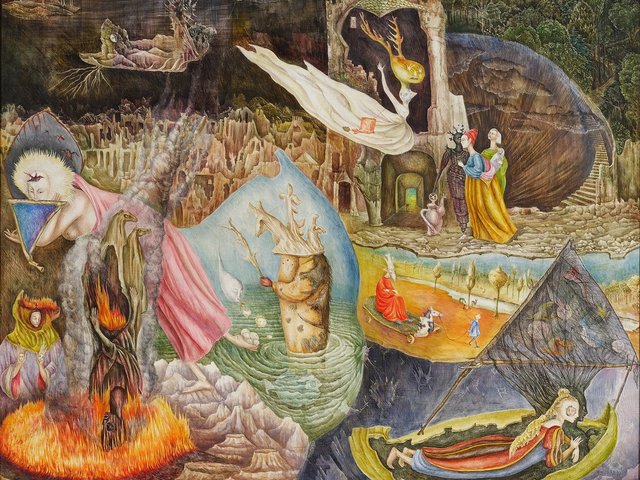

The Milk of Dreams, published in 2013, and illustrated with the drawings Leonora created to accompany her tales, was seized upon by the organiser of the Biennale, Cecilia Alemani, who said the book detailed “a magical world where life is constantly re-envisioned through the prism of the imagination, and where everyone can change, be transformed, become something and someone else”. Alemani has highlighted the interconnectedness of everything as a fundamental theme for so many of the issues of the current moment—and this, as well as ecology, feminism, and spiritual meaning outside of organised religion—is one of the transcending themes of Leonora’s work, both her writing and her art.

Gabriel says he believes his mother’s work “opens possibility: she gives you the possibility to imagine. She gives you this kind of leeway”. In his own recently published memoir The Invisible Painting: My Memoir of Leonora Carrington, Gabriel writes about how, in her final months, his own sons Pablito and Daniel would read their grandmother the stories of The Milk of Dreams, which Leonora would have loved (Leonora was the cousin of this writer’s father, and Moorhead knew her in the last five years of the artist’s life). “For her, it was almost like listening to the work of another author,” Gabriel says.

What, though, does Gabriel think his mother would have said about the Venice Biennale—the oldest and most prestigious international art exhibition—being named after her book, with themes inspired by her work? “I think she would have been very unimpressed—but then she would have been glad,” he says. “She would have had a mixed reaction. She would have said something iconoclastic, and the next moment she would have said, that’s interesting, why? Why are they interested in my work?”

What Gabriel and his brother Pablo hope is that the Biennale will open their mother’s work to a new audience, amid signs that her legacy is gaining a new level of traction across the art world. Over the past three years galleries including MoMA in New York, Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, and the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh, have all acquired important new works by Leonora, and a major show of her work is planned for Denmark and Spain next year.