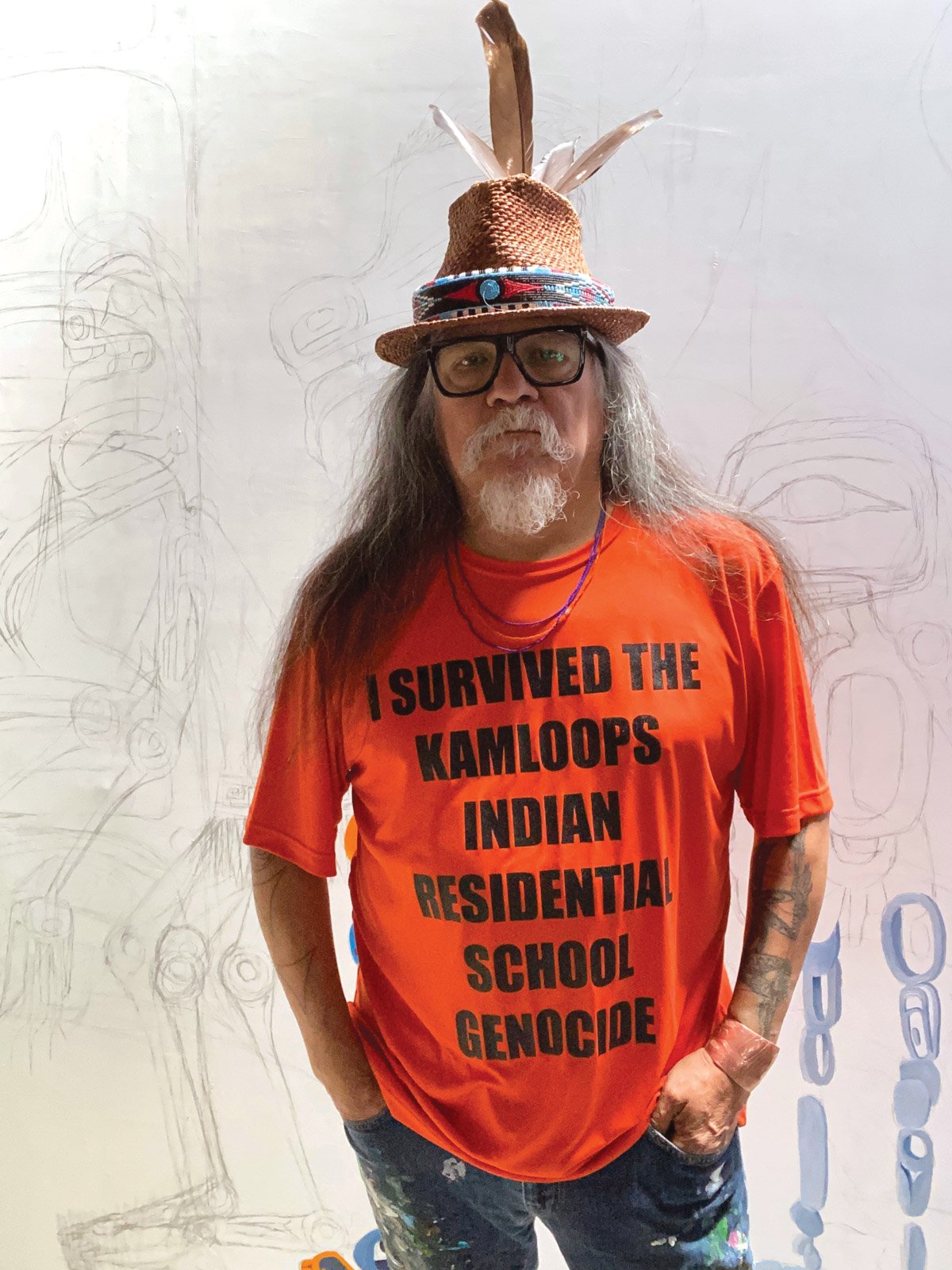

When Cowichan/Syilx First Nations artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun first heard the news that the remains of 215 Indigenous children were found in unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, he felt a familiar pain. “We’ve known about it for a long time, from the stories of elders and survivors,” the 64-year-old artist tells The Art Newspaper, during a virtual visit to his studio in East Vancouver. But when these stories were confirmed by ground-penetrating radar, it brought back memories of his own experiences at the notorious school, where he spent three years as a student, from kindergarten to second grade.

While it was too difficult for him to return to the physical site of the tragedy, where friends were engaged in healing ceremonies, Yuxweluptun instead retreated to his studio for contemplation. “I cried and said prayers for their spirits, and I put out bread and water for their journey on a tree stump,” he says. He also started working on a new painting, entitled Spirit Child Walking Home.

Rendered in Yuxweluptun’s unique style, a blend of traditional Northwest Coast formline design and cosmology, surrealism and intrinsic political commentary, the painting recalls his 1990 canvas Red Man Watching White Man Trying to Fix Hole in Sky. But in this piece, the colourful central figure is framed by two cedars in brown and green earth tones, depicted as friendly spirit guardians helping the child on his journey. “Now that the children’s spirits have spoken to us, it’s time for them to go home,” says the artist. “I hope my painting will help them get there.”

Creative response

Like many First Nations people in Canada who have spoken out about residential school abuse for decades, Yuxweluptun has documented it through his art as well. While he was trained by his father in traditional carving and graduated from Vancouver’s Emily Carr University of Art and Design in 1983, it was not until 2005 that he explicitly articulated his own experience with his powerful Portrait of a Residential School Child. “It was just too painful to do anything before then,” he says.

Yuxweluptun’s Portrait of a Residential School Child (2005) was the artist’s first response to his time at Kamloops Courtesy of Macaulay & Co. Fine Art and the artist

In his portrait, Yuxweluptun simultaneously subverts and incorporates the Christian halo by fusing gold leaf with traditional images of human guardian spirits and the four directions. The painting is a response to the church’s dehumanisation of Indigenous peoples, the artist says, and his intent was to show that “the child—given a traditional salmon/trouthead eye—is sacred and that they killed his body but not his spirit”.

Yuxweluptun recalls the horror of seeing his classmates die. One six-year-old friend died from a tick bite—something that would have been attended to if she had been allowed to stay with her parents, he says. When a law allowing First Nations people to leave the reservation was passed a few years later, and Yuxweluptun finally went to a public school, he remembers asking his father, “Dad, why don’t they have a graveyard here?”

Yuxweluptun’s father was a survivor of another residential school, where he had his teeth pulled out without anaesthesia, among other cruelties. His father was also a woodworking instructor at the Kamloops school because the local public school would not hire him.

In 2013, Yuxweluptun’s multimedia work Residential School Dirty Laundry made an even stronger statement, referencing the rape of children by school priests. Formed from hundreds of pairs of white children’s underwear in the shape of a cross, the artist painted drops of blood where the traditional stigmata would be. In the centre, a plaque reads, “For this child, I prayed...”, a bible verse from the first book of Samuel.

Yuxweluptun has taken to wearing a chain around his neck, attached to a copy of the Indian Act with bullet holes in it, a remnant of his 1997 work An Indian Act Shooting the Indian Act

Apartheid bling

Since news broke of the Kamloops school mass grave, followed last week by another grim discovery of 751 bodies at the at the Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan, Yuxweluptun has taken to wearing a chain around his neck, attached to a copy of the Indian Act with bullet holes in it, a remnant of his 1997 work An Indian Act Shooting the Indian Act. In this performance art work, Yuxweluptun shot a copy of the colonial legislation that allowed the Canadian government overarching political control of Indigenous communities—and which is still in effect with amendments. It has been repurposed as a necklace the artist calls “apartheid bling”.

Yuxweluptun’s powerful painterly narratives, sculptures and multimedia works—some of which are part of an exhibition with the Anishnabe artist Charlene Vickers at Macaulay & Co. Fine Art in Vancouver until 4 September—are matched by his unrelenting activism and calls for accountability.

“I make art to speak to the world, and I want the UN to come and see what has happened here,” he says. “I want those priests and administrators who abused children to be named and charged.”

Rejecting what he calls “smug Canadiana” and a false narrative about tolerance and diversity, Yuxweluptan wears his “bling” as he prepares for a show at New York’s Garth Greenan Gallery in October.

The chain will eventually be at the centre of a forthcoming performance piece, Yuxweluptan says, to raise some important questions: “When will we emancipate the Indian? How do I become free? Can you be a free person in an apartheid state?”