Sarah Schulman’s new brick of a book, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993, which draws on 20 years of interviews that she did with nearly 200 Aids activists as well as her own experiences in the group, could not come at a better time. Published as another pandemic throws systemic racism and healthcare injustices into relief, her book offers such detailed accounts of how ACT UP (the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) confronted government apathy, religious bigotry and corporate greed that Parul Sehgal in the New York Times called it “a tactician’s bible”, with other critics more bluntly urging a younger generation of activists to read it.

Any artist-activists today who are tempted to work within the art-world infrastructure to build visibility for their causes should also study up. According to Schulman’s book, the most powerful ACT UP projects and performances took place outside of museum walls and the gallery system. Not just because the public-oriented or street-based artworks reached a different audience, but because they were fundamentally different in their make-up: less complicated and more focused, less contemplative and more urgent.

One example she gives on the complicated, art-world end of the spectrum is Let the Record Show…, a 1987 installation in the windowfront of the New Museum by the ACT UP art collective Gran Fury, which took their name after the type of unmarked cars that police used for surveillance. Invited to make a work by the New Museum’s curator William Olander, Gran Fury created a photo backdrop showing the Nuremberg trials and in front placed cardboard cut-outs of six “criminals” of the AIDS crisis, including Jesse Helms and Ronald Reagan, amid tombstone images and damaging quotes from them and a LED display running statistics on the epidemic. Despite attention from the historian Douglas Crimp, the artwork proved too disjointed to reach many people—“It was a mess… just a lot of minutiae,” said Gran Fury artist Marlene McCarty.

Gran Fury's installation Let the Record Show . . . at the New Museum, New York, 1987 Photo: Fred Scruton

Infinitely more effective was the sparse “Silence=Death” slogan that some members of ACT UP created before the group officially started, with white type on a black background and a pink triangle above it, reclaiming the upside-down pink triangles used in Nazi concentration camps to brand gay men. That of course became the organizing image of ACT UP, the image wheat-pasted all over New York before appearing on t-shirts and other objects (it was inserted in the New Museum window as well), and Schulman gives a fast-paced, almost sportscaster-style account of how a handful of artists, including Avram Finkelstein (later of Gran Fury), sharing a desire to create an artwork as succinct as advertising, each contributed to its final form.

As for the bigger issue of how to structure collaboration, not only does Schulman dismantle the myth that ACT UP was led by gay white men (who got more than their share of media coverage), she reveals that in many ways it didn’t have a leader at all. Nor did it have a mandate for participants to agree on priorities and actions. During “its height of influence,” she wrote, “ACT UP never demanded full agreement for an action or campaign to be taken up.” For example, she says, if she wanted to participate in an illegal needle exchange “in order to get arrested and wage a test case trial”, but another member did not want to be involved, “you wouldn’t stop me from doing it; you just wouldn’t do it. If instead you wanted to organize a demonstration against the Catholic Church, and I didn’t want to, I simply wouldn’t do it.”

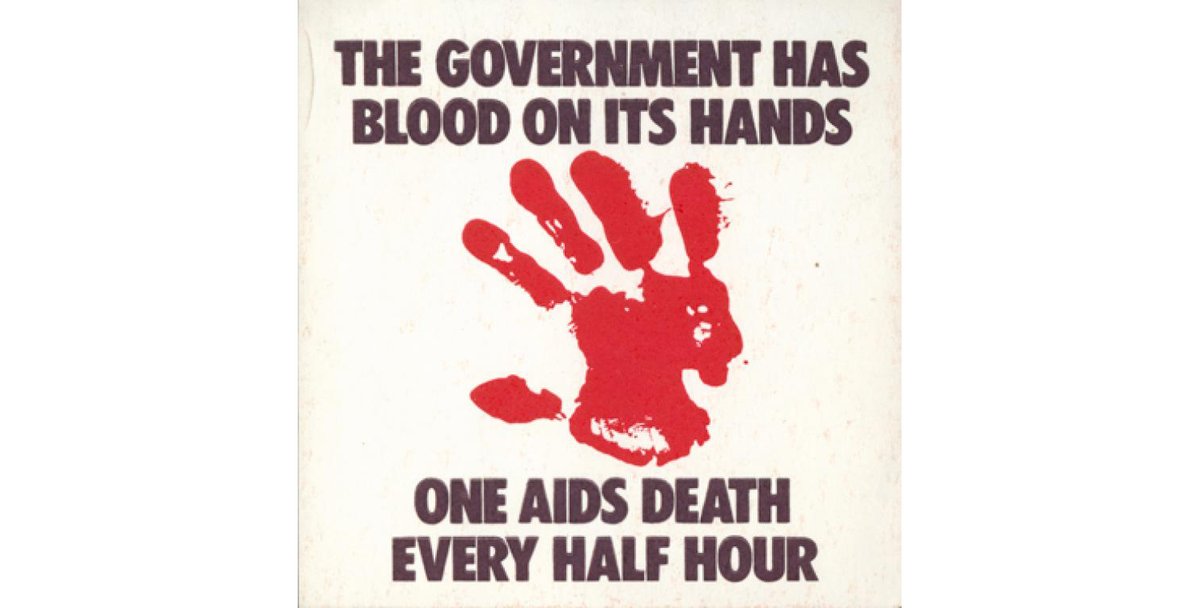

Given a rapidly spreading and horribly debilitating virus—"the government has blood on its hands/one AIDS death every half hour,” announced a Gran Fury artwork from 1988—moving quickly on many fronts at once had practical advantages. But it is also clear that Schulman believes this model of everyone setting their own agendas, which she calls “radical democracy,” is more creative, flexible and self-fulfilling than the sometimes overly careful, consensus-based decision-making that shapes and also hinders many grassroots activist movements today.

Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993

And even though she does not say it quite as explicitly, the artists groups in ACT UP reflect this democratic impulse too. Artists who did not work with the Gran Fury—which after a year decided to limit itself to around 10 core members—ended up creating other “affinity groups.” One was Action Tours, which did dozens of theatrical guerilla actions like infiltrating government buildings dressed as tourists and then splashing themselves with fake blood. Another was Gang, which was closer in spirit to Gran Fury.

Meanwhile Catherine Gund, an alumnus of the Whitney Independent Study Program (which she called in her interview a “one-year Marxist-indoctrination studio-art programme in downtown Manhattan”) was instrumental in another group, known for training video cameras on the police during protests to hold them accountable. It was called DIVA TV, short for Damned Interfering Video Activists Television, which points to another lesson from the annals of AIDS activism: the power of a memorable acronym.

• Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993, Sarah Schulman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 736pp, $40