The British-Ghanaian photographer James Barnor made his start on the streets of Accra in pre-Independence Ghana using borrowed equipment. By 1953 he had started his own studio called Ever Young in the Jamestown area of Accra, which was visited by civil-servants, dignitaries, artists and newly-weds alike. The images he took there were ostensibly formal portraits but set against elaborate painted backgrounds and, thanks to his rapport with his sitters, they fizz with energy.

“He said his studio was a little bit like a community centre,” says Lizzie Carey-Thomas, the curator of a forthcoming survey of Barnor’s work at the Serpentine North Gallery in London. “[The studio] was next to one of the most well-known hotels in Accra, and so he had a steady flow of people dropping in to see him all day and all night.” Visitors would come for a variety of reasons: passport photos, family portraits or just because they fancied hanging out. “There’s a wonderful photograph of a troupe of comedian actors who just came in one night to have their photograph taken,” Carey-Thomas says.

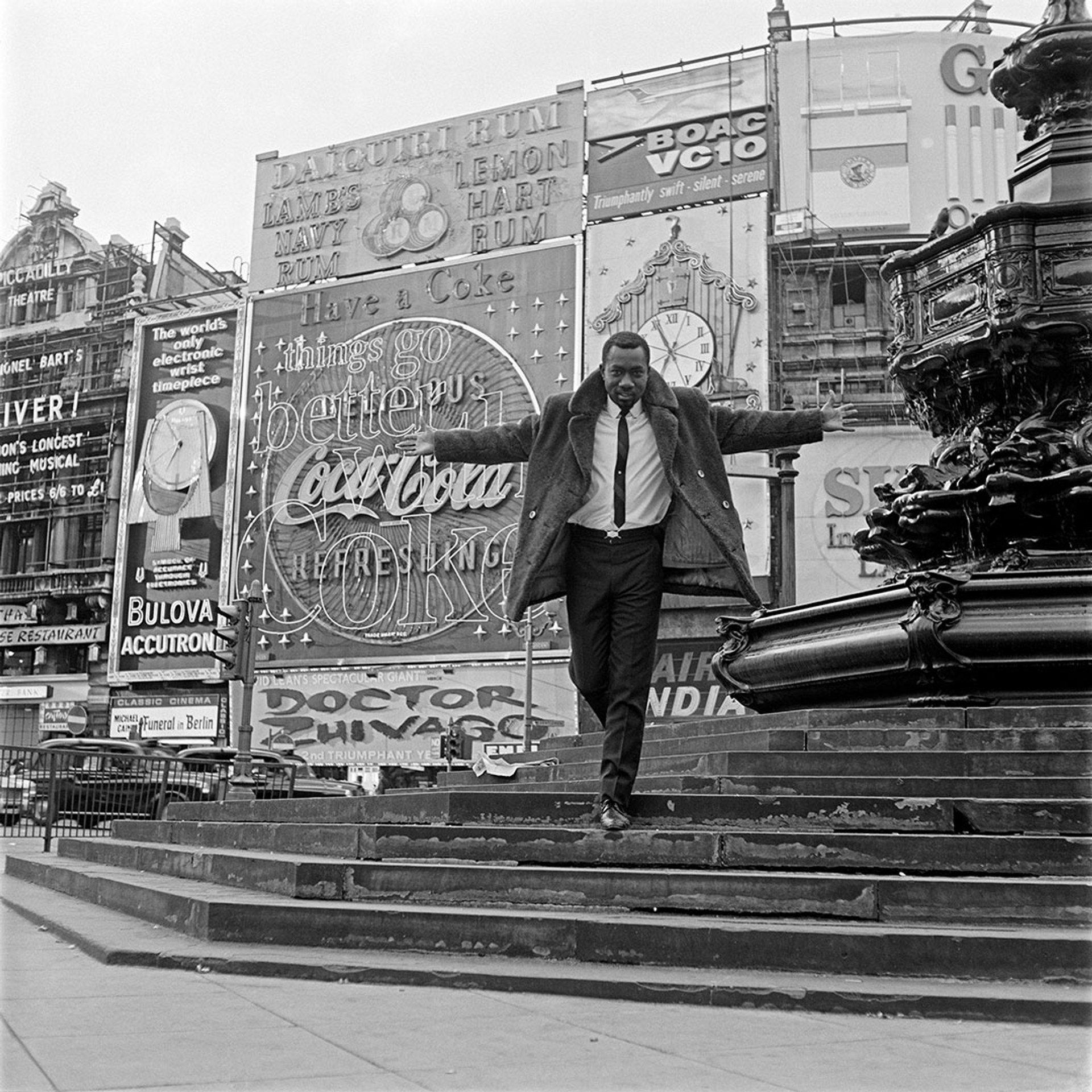

Barnor's Mike Eghan at Piccadilly Circus, London (1967) Courtesy of Autograph

A couple of year after Ghana gained independence from British colonial rule in 1957, Barnor travelled to the UK where he continued his studies and worked on commissions for the South African magazine Drum. “He had a very particular experience in London in the 60s,” Carey-Thomas says. “He is very keen to highlight that he had a lot of very serendipitous meetings.” One being with a photographer and Kodak employee called Dennis Kemp, who took Barnor under his wing and encouraged him to further his studies, which he did, at the Medway College of Art in Kent.

“People are more important than places,” Barnor has often said. His portrait-heavy practice is at its apex in his assignments for Drum magazine, focusing on the glamourous fashions and idiosyncratic characters of swinging London. Amongst the most recognisable images he took for the magazine is a 1967 photograph of the BBC broadcaster Mike Egan, arms outstretched in the middle of Piccadilly Circus. Barnor’s assignments also focused on Black models such as Erlin Ibreck who he met in a bus queue at Victoria Station and whose portraits will features heavily in the exhibition.

Barnor's Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck Kilburn, London Courtesy (1966) Courtesy of Autograph

Barnor’s rapport with his sitters comes across in the electric encounters with boxers such Roy Ankrah, nicknamed the Black Flash, and Muhammad Ali, who was preparing to fight Brian London in 1966. The boxers in these images are not passive subjects but part of the process; they are personal encounters.

Barnor always wanted to return to Ghana, and in the early 1970s he set up a colour processing laboratory and opened his portrait studio Studio X23 in Accra. The striking images from this period show a post-independence Accra blossoming, with incredible fashion, peppered with 1970s lapels and platform boots. He moved back to the UK in 1994, where he now lives.

Barnor's Members of the Tunbridge Wells Overseas Club, Relaxing after a Hot Summer Sunday Walk, Kent (around 1968) Courtesy of Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière

There are around 40,000 images in Barnor’s archive. “There are no duds,” Carey-Thomas says. These varying strands of activity, explored in the Serpentine exhibition, bridge continents and photographic genres, documenting the huge socio-political changes in both Ghana and the UK through one man’s eyes and lens.

• James Barnor: Accra/London, a Retrospective, Serpentine North Gallery, London, 19 May-22 October