The success or failure of Frieze New York could have consequences throughout not only the art fair circuit in the US and abroad, but very likely for other cultural institutions that plan to hold events and are looking at the city's first major cultural gathering in more than a year as a barometer for post-vaccination attendance. Will it work? If the opening day of the fair is any indication, the answer is a flat out yes.

Similar to the way elite athletes, pro-tennis players or boxers train in privacy for months prior to a tournament or championship bout, Frieze’s organisers spent months planning their relocation to the Shed. The announcement of the move to Manhattan from Randall’s Island was made in late October last year, but The Art Newspaper was told conversations began some months before that. And since that very well received relocation began to take shape, the organisers have planned for contingencies and worked with exhibitors to make sure adjusting to the safety protocols would not disrupt the business of selling art.

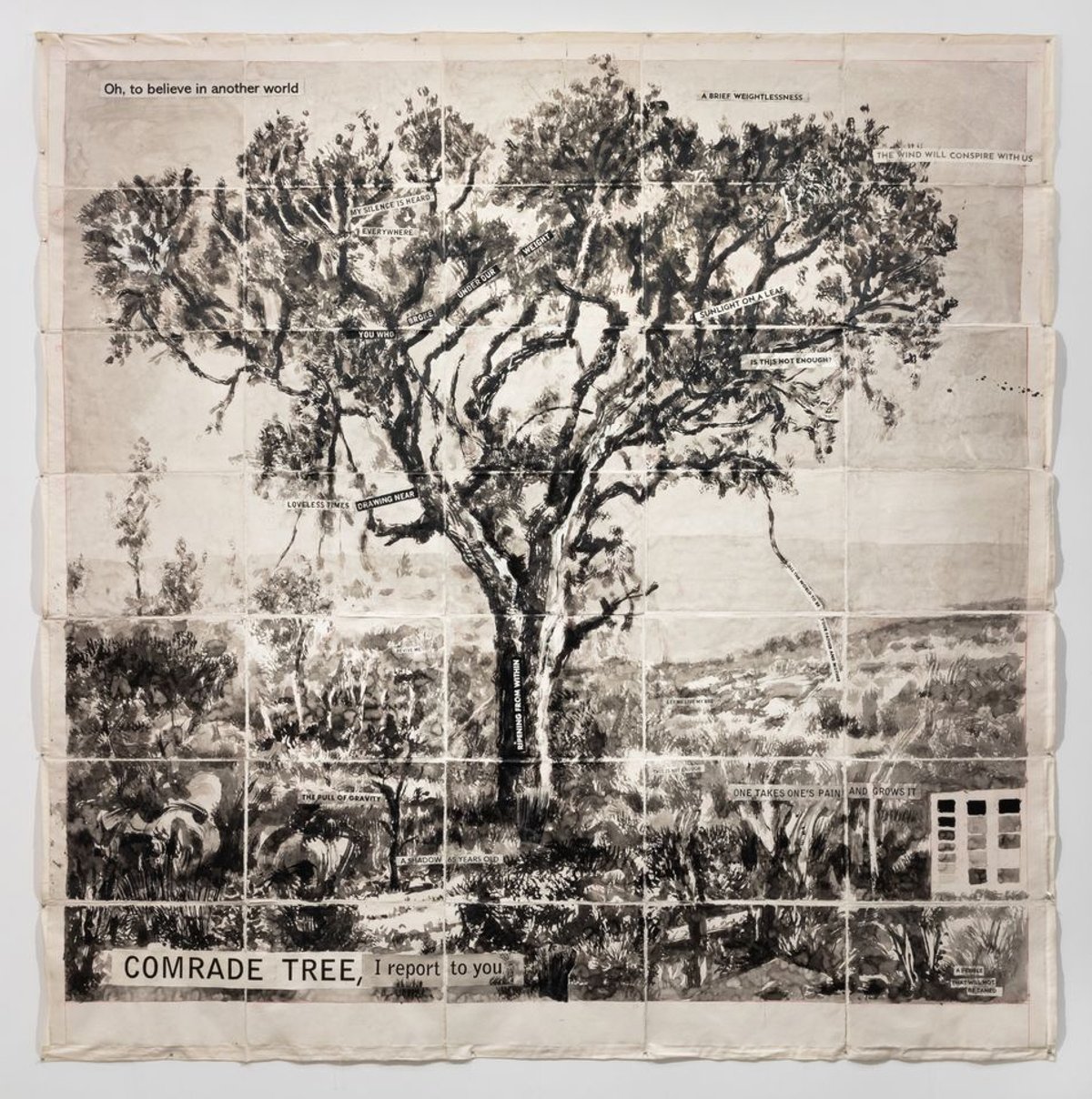

“This feels like a real revival, like it’s Spring in the art world,” says Goodman Gallery’s new US senior director Denis Gardarin from their booth on the Shed’s expansive second level. Gardarin praised the fair, which he says made the install and Covid-19 testing protocol “painless, it’s just a small adjustment to the new systems”. Nearly all of the work in Goodman’s booth sold by midday, including William Kentridge’s organic, earthy ink wash, red pencil and collage piece Drawing from Waiting for the Sibyl (Comrade Tree, I report to you) (2020), which went to a private US collection for $700,000.

Frieze New York 2021 at The Shed Photo by Casey Kelbaugh. Courtesy of Casey Kelbaugh/Frieze

Both the feeling of relief and release permeated throughout the fair, with exhibitors having leisurely conversations with potential buyers, and fair-goers running across the grounds to bump elbows and exchange an “Oh my god, I can’t believe how long it has been.” Gallery owners, too, hopped from booth to booth to greet old friends, comrades and former co-workers. At Gagosian, there may have even been some tap dancing.

But while the general energy was upbeat, the pace of the fair felt calm, due in large part to the timed entrance, which helped prevent the traditional stampede of collectors, appreciators, and the fashionably aloof. It is as if Frieze, now a little more mature, has given up its crashpad in the outer boroughs and moved into Manhattan. “It’s a more civilised way of buying. There’s still the energy, but not the mad rush like there used to be,” Gardarin says. Jacob Robichaux, of New York-based Gordon Robichaux, described the atmosphere in a similar, albeit in less embellished way. “It’s more humane for the people working here, for the exhibitors and the staff. There’s not the feeling of being pulled at from all sides and you have the comfort of knowing collectors will be coming tomorrow as well,” Robichaux says. “It’s a good transition back into networking with the people we’ve been distant from for so long.”

The gallery, part of the fair’s Frame section, was showing a solo exhibition by Otis Houston Jr, and propelled by a New York Times profile of the artist published the previous day, sold over half of their booth with many pieces on reserve for the following day. The works, which include appropriated images, work on towels and paintings, sold for between $5,000-$15,000. Also in the Frame section, Los Angeles-based Chateau Shatto sold three large pieces by the London-based Kenyan artist Zeinab Saleh for £7,500-£8,500 each, including the gossamer Preparing my daughter for rain (2021).

Dawoud Bey A Girl with School Medals, 1988 © Dawoud Bey Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

Sean Kelly Gallery’s corner booth was one of the focal points of the day, with exciting work on view and more than its share of conversations and reunions in and around the booth. Sales followed in kind. Dawoud Bey's large-format portrait of a young girl leaning on a fence, staring intently back at the viewer, A Girl with School Medals (1988), sold for $15,000. An edition of four with two artist’s proofs, the image can also be seen at Bey’s exhibition at the Whitney Museum. Idris Khan’s Each Second and Second, (2020) a deep blue C-Print resembling an ocean of sheet music sold for £75,000, and Shahzia Sikander’s over six-foot tall ink and gouache on paper piece, Mirrored (2019), brought in $125,000.

Detail from Cynthia Daignault's 26 Seconds, (2021) Courtesy: Kasmin, New York. Photography by Diego Flores.

For Kasmin’s Nick Olney, there were multiple highlights to opening day, not the least of which was introducing new artists to new collectors—and being able to do so in person. “People were just excited to be here. Especially since it was in the city. There’s a feeling that you’re threaded right into Chelsea, you’re part and parcel with all the galleries. People don’t mind the timed entry or the two-hour time limit because they can explore the gallery district before or afterwards,” Olney says. Kasmin sold 12 works on opening day priced between $8,000–$350,000 by artists including Cynthia Daignault, Liam Everett and Jan-Ole Schiemann. Daignault’s oil on linen work, 26 Seconds (2021), nine panels at 10 x 15 inches each, showing a cinematic view of the JFK assassination, sold for $48,000.

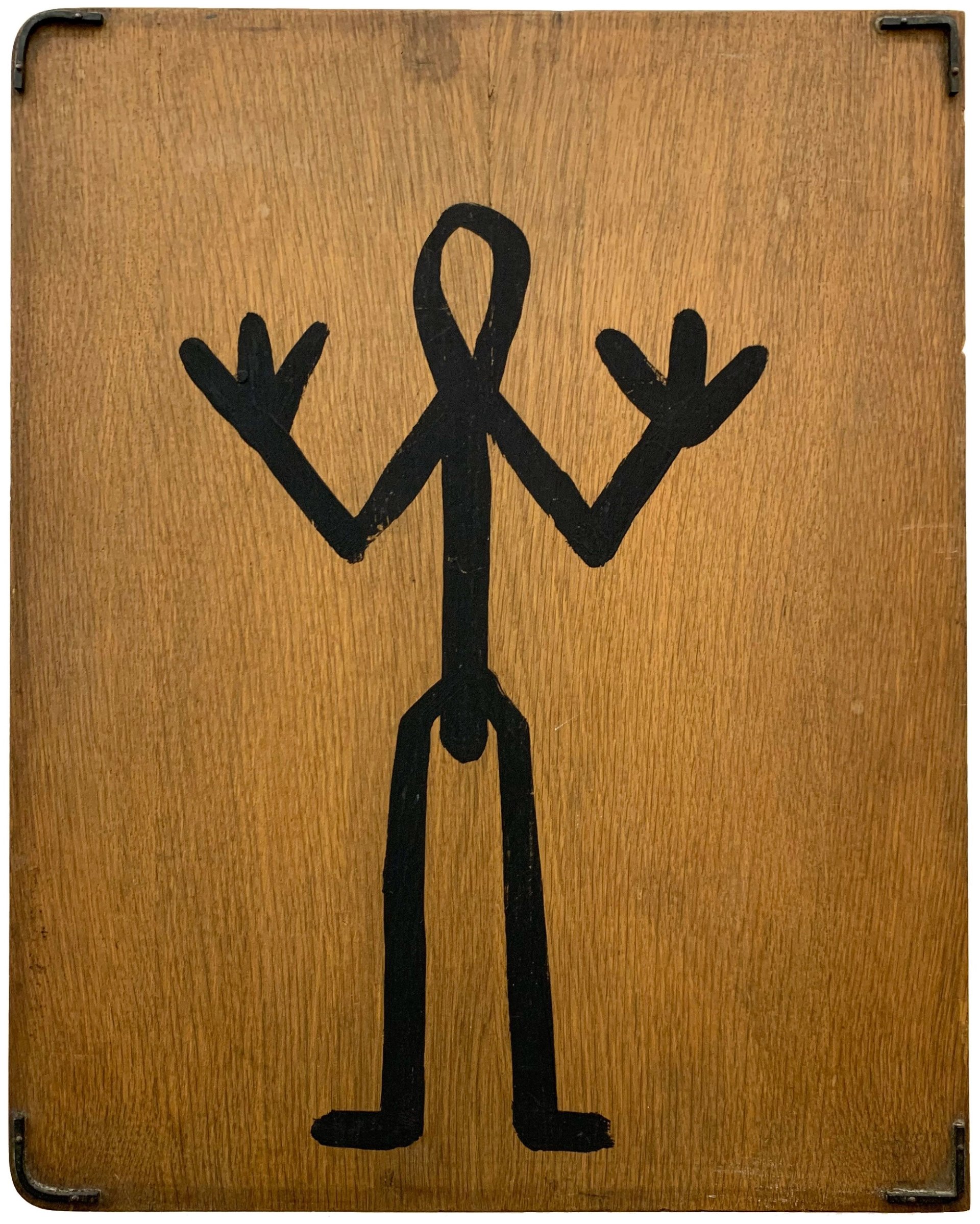

Michael Werner Gallery brought a number of important works of art to Frieze New York. “It’s the first fair back, the first time we are all together. We wanted to make sure we recognised the weight of that and brought work that would be on par with the day,” Gordon VeneKlasen says. They sold a number of pieces including three by Enrico David priced between $15,000-$50,000, and an A.R. Penck, Standart (1967), which sold for $450,000. “It’s a key piece for Penck, that began his Standart period. It was the beginning of everything for him. We sold it once in 1992 and recently reacquired it. I brought it to the fair and the was quite a lot of interest. I was actually surprised. People here are not just looking at inexpensive things,” VeneKlasen says.

A.R. Penck, "Standart" (1967) Courtesy: Michael Werner Gallery