Vincent van Gogh was always on the move, looking for new places to develop his art. He worked in cities such as The Hague, Antwerp and Paris, in villages in his native Brabant, in Provence and finally in Auvers-sur-Oise. His life has been studied by art historians and biographers in minute detail, but his period in Drenthe, a remote province in the north of the Netherlands, remains more of a mystery.

That is set to change, with a new publication and an exhibition. Van Gogh: Heritage Locations in Drenthe—prepared by the province’s museum, archive and landscape foundation—provides a detailed guide to 15 sites linked to the artist. A major exhibition, which should include all of the artist’s Drenthe oil paintings, is being planned by the Drents Museum in the provincial capital, Assen.

Before arriving in Drenthe, Vincent had lived in The Hague for two years, sharing a modest apartment with a woman named Sien, who until their relationship had worked as a prostitute. She then had a five-year-old daughter and would soon have an infant boy (by another man). Vincent’s relations with Sien had sadly deteriorated by 1883 and he found city life with little money was dispiriting.

Longing for “the real countryside”, Van Gogh set off for Drenthe in September. Initially he stayed in the small town of Hoogeveen, but then travelled on a horse-drawn canal boat to the remote village of Nieuw-Amsterdam, near the German border. It was, he said, “the very back of beyond”.

From Nieuw-Amsterdam, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo: “I now have a reasonably large room where a stove has been placed, where there happens to be a small balcony. From which I can even see the heath with the huts. I also look out on a very curious drawbridge.” Downstairs was “an inn and a peasant kitchen with an open peat fire, very cosy in the evenings”. As autumn drew on it was “really snug, with the light from the little windows reflected in the water or in mud and puddles”.

The new drawbridge in Nieuw-Amsterdam Photo: Sake Elzinga

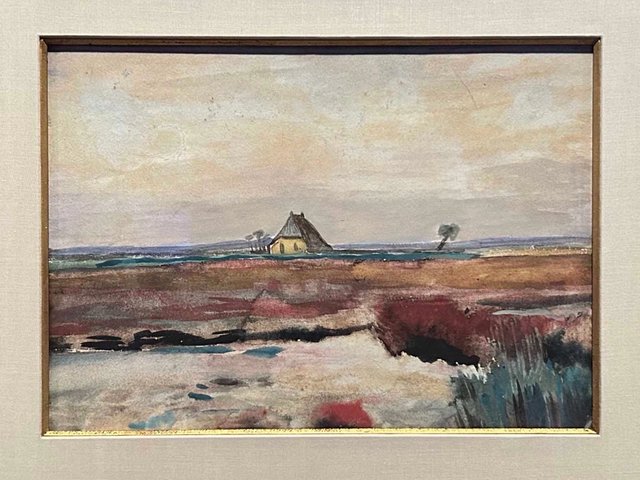

Van Gogh made a watercolour sketch of the scene from his balcony, looking over the canal towards the peat bogs. The 1860 bridge has been replaced by a steel one erected in 1956. Sadly the building just to the right of the drawbridge in Van Gogh’s painting was demolished as recently as 1998, a heritage loss for Nieuw-Amsterdam.

Fortunately the former inn was saved and in 2003 it was transformed into a visitor centre dedicated to the artist. Although the Van Gogh House Drenthe has none of his artworks, his former bedroom can be seen, together with a display about his period in the province.

Van Gogh House Drenthe, Nieuw-Amsterdam Courtesy of Drents Museum, Assen; photo: Sake Elzinga

Very early one morning, at 3am, Van Gogh took a ride with his Nieuw-Amsterdam landlord to reach the village of Zweeloo—a three-hour journey in an open cart. There he made an atmospheric watercolour, Shepherd with Flock Near the Little Church of Zweeloo (1883). Describing the scene to his brother, he wrote about seeing the return of the flock at dusk representing “the finale of the symphony that I heard”.

Van Gogh’s Shepherd with Flock Near the Little Church of Zweeloo (November 1883) Private collection

Dating back to the 13th century, the church’s red-brick exterior remains relatively unchanged since Van Gogh’s time. Tall trees have since grown up around the building.

The Dutch Reformed Church at Zweeloo Courtesy of Drents Museum, Assen; photographer Sake Elzinga

Van Gogh’s watercolour was privately sold in the early 1990s by a dealer with a gallery in London and the Netherlands. It is now in an unknown collection. The Drents Museum curator Annemiek Rens is keen to track it down, so she can submit a loan request for the coming exhibition. It would be a particularly important work, partly because of Van Gogh’s lyrical description of his excursion to Zweeloo.

Although it is unusual for exhibitions to be announced so far in advance, Van Gogh in Drenthe will open on 11 September 2023, the 140th anniversary of Vincent’s arrival. Rens hopes to assemble all five of the artists’s surviving Drenthe oil paintings, along with a considerable number of drawings, watercolours and documents.

In December 1883 Vincent finally left Drenthe, to move to his parents’ home in Nuenen, in the far south of the Netherlands. He wrote to Theo: “Drenthe is superb, but staying there depends on many things—depends on whether one has the money for it, depends on whether one can endure the loneliness.”