Publications and exhibitions abound this year honouring Dante, the poet and author of the epic masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, on the 700th anniversary of his death. In Visions of Heaven: Dante and the Art of Divine Light, the scholar Martin Kemp presents a unique thesis, examining how Renaissance painters such as Titian and Raphael were influenced by Dante’s conception of divine light.

Indeed, Dante set the bar high. “A succession of major artists grappled with the portrayal of divine light in emulation of Dante’s account of its blinding intensity and failure to obey optical rules,” Kemp says. The extract below outlines how Sandro Botticelli approached The Divine Comedy, creating his finely wrought depiction of Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso, accompanying texts written by the scribe Niccolò Mangona. The late 15th-century series, of which 92 illustrations survive, may have been commissioned by the patron Lorenzino di Pierfrancesco de'Medici, Kemp says.

Sandro Botticelli's illustration Beatrice and Dante Who Shades His Eyes, in the Heaven of the Sun, in Dante's book La Divina Commedia, Paradiso, Canto IX Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett

The illustrations for Inferno and Purgatorio adopt complex narrative modes, like some of the Mediaeval manuscripts, in which Dante and Virgil not infrequently feature two or three times on the same sheet, at different stages in their laborious journey. The compositions are notably varied, with considerable freedom in how the space is handled, often in a non-perspectival manner. It is clear that Botticelli has read the text with close attention. The drawings for Paradiso are startlingly different. They are dominated by beautifully drawn and characterised images of Beatrice and Dante conversing, frequently with no other setting than a heavenly circle drawn with compasses. Fifteen illustrations included no more these three elements. A further seven added orbiting tongues of flame to this basic format.

Five images show airborne angels, including a heavenly choir in massed ranks in what is an unusually dense image. This leaves two with slightly more elaborate settings, and one so unfinished as to be indeterminate. Had the illustrations been finished, we may imagine that the circles (spheres of the heavens), the gesticulating figures and the backgrounds would have been coloured in, but there is no indication that most of what Dante described would have been included.

The front cover of the new book Visions of Heaven: Dante and the Art of Divine Light by Martin Kemp (Lund Humphries)

Compared to the Holkham and Giovanni di Paolo manuscripts [other versions of the Divine Comedy], there are no standard images of the Virgin and Child, no recognisable saints, no planetary deities, no ancillary figures such as the fishing mermaid, no ‘experiment’ with the three mirrors . What is Botticelli saying? In the most radical way, he is not letting us envisage Dante’s visions in the normal figurative manner. Dante nowhere says that he saw the saints in heaven as the kind of people in clothes that we see on earth. The rings of flaming light, translated into pure love, are the visible manifestations of the saints, and it is in this form that they speak and are identified. On seven occasions we see Dante and Beatrice encircled by nine heavenly circles of flames ‘like comets’.

In the illustration to Canto XXIV, the mighty St Peter questions Dante on his level of faith. Beatrice intervenes on her companion’s behalf. The largest of the flames one rank above Beatrice’s searching gaze is labelled ‘pietro’. At the centre of the whirling flames is a radiant sun-face, that of Christ, of supreme brightness but not embodied. The various types of angels are, however, shown; we do see them on occasion. They are intermediate figures, messengers sent to earth and operating in Purgatory. To make sense of Botticelli’s minimalist representations of the saints and holy figures, we have to imagine the sound of the text being read. The speaking flames emit voices.

The sequential figures of Beatrice and Dante in each drawing move in an almost cinematic manner. Typically, Dante’s gestures, glances and expressions are more limited than his companion’s. He predominantly reacts in a docile manner. When he raises his hands it is to ward off unbearable brightness or to express surprise and bewilderment. Beatrice, who sometimes seems to look at us, points instructively upwards and downwards, guiding Dante visually and physically. A particularly telling moment is in Canto XXI, when they have reached the seventh and outermost sphere of the planets.

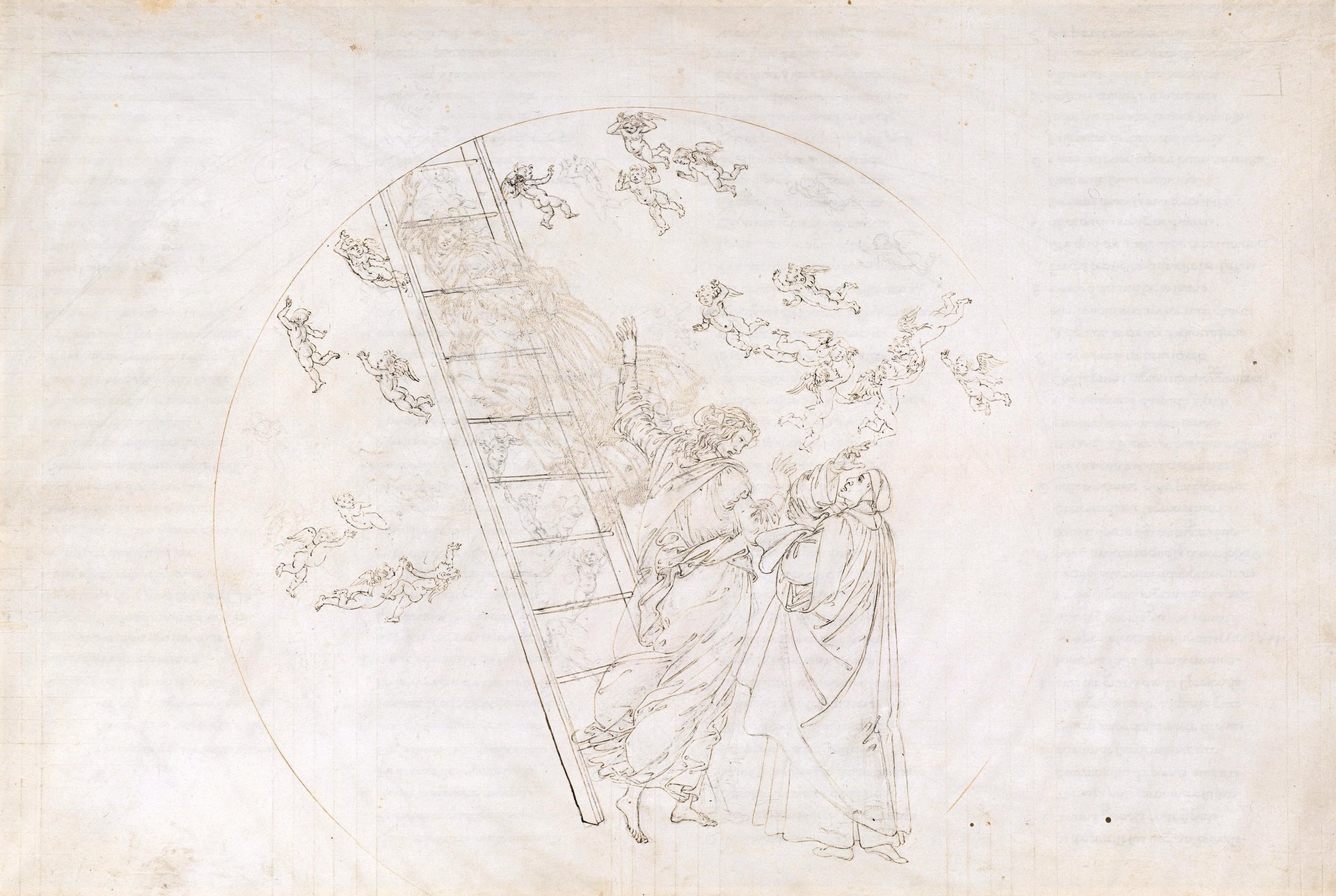

Sandro Botticelli's drawing Jacob’s Ladder for Dante's La Divina Commedia, Paradiso, Canto XXI Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett

The ladder of Jacob is placed to conduct them to the sphere of the fixed stars. Beatrice, graceful and light-footed, signals the climb they should undertake. At one point, Botticelli was thinking about also showing their actual ascent, but this has been partially erased and becomes the subject of the next drawing, in which Beatrice actively lifts the timorous poet. When they have ascended even further to the Primum Mobile, she instructs Dante to look downwards to see how magnificently far they have risen. They have ascended to a place of ‘triumphant mists’, from which they then levitate spiritually to the final zone of God’s heaven.

The last of Botticelli’s illustrations is for the penultimate canto. It is very unfinished and shows a very small and distant sketch of the stigmatised Christ and the Virgin, just visible in corporal form at last, with an attendant angel, but there are only a few hints as to how in his abstract mode he could have described the massive celestial rose and its teeming population. For the last canto, with its vision of the Trinity, nothing survives.

In his Paradiso illustrations Botticelli’s abstinence is heroic and profound, even taking into account that his drawings would have been coloured. No-one comes near his daring level of spiritual minimalism. Other illustrators feel a need to embody the speaking flames of the saints’ spirits. John Flaxman, the neoclassical sculptor in the late 18th century, used spare and simple lines with great economy in his set of refined illustrations, but even he felt obliged to give corporeal and costumed form to some of the major saints and holy figures.

It seems impossible that the illustrations could have been realised in a printed book of such size and orientation. We are dealing with specially commissioned images for a discerning private patron. If that patron was indeed Lorenzino [di Pierfrancesco de'Medici], he is to be congratulated on stimulating the greatest of all the illustrated Dantes– but also offered commiserations that the majestic project was never finished.

• Visions of Heaven: Dante and the Art of Divine Light, Martin Kemp, Lund Humphries, 240pp, £45.00 (hb)