The quincentenary of Raphael’s death in 2020 produced a crop of books and exhibition catalogues, nine of which have been received for review by The Art Newspaper; a tenth, published in 2017, rounds out this assessment of books on the artist.

Marco Bussagli’s monograph covers Raphael’s entire career, but unevenly. Some areas have engaged Bussagli’s interest deeply, others are neglected. Unusual in its construction, the book comprises an introductory overview, a section discussing five significant themes in Raphael’s work, and a catalogue of 39 paintings, divided into opere minori, opere grandi and capolavori. This selective approach has gains and losses: for example, Giovanni Santi’s importance as a model for his son is well analysed, but Raphael’s Florentine period is treated skimpily. There are also some odd datings. But Bussagli’s book, heavily influenced by Claudio Strinati’s adventurous monograph of 2011, is vigorously written, and benefits from a novel design, with charming circular close-up details orbiting the larger images.

The exhibition Raffaello e gli amici di Urbino, mounted in Urbino in 2019-20, centred on Raphael’s relations with Timoteo Viti and Girolamo Genga, but extended to cover their later careers. With well co-ordinated essays and entries, the catalogue offers welcome accounts of both artists and includes some new paintings and drawings (one entry, incidentally, corrects an egregious misattribution of my own).

The Urbino show was complemented by an exhibition devoted to the collection of “Raphael Ware”—majolica produced mostly at Castel Durante—in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria. Demonstrating the wide range of sources employed by ceramic painters, the catalogue is a valuable addition to the majolica literature.

Raphael became Rome’s leading architect, responsible for St Peter’s and the Villa Madama

The other volumes under review make it clear that scholarly attention is now focused on Raphael’s later Roman years. During the pontificate of Leo X (1513-21), Raphael’s activity expanded vastly: he became Rome’s leading architect, responsible, among other projects, for its grandest sacred and secular schemes, St Peter’s and the Villa Madama, and his concern with theory prompted him to edit for intended publication an Italian translation of Vitruvius. Involved in town planning and archaeology, Raphael sought to itemise and preserve the remains of ancient Rome, of which, when he died, he was attempting an enormously ambitious visual reconstruction. Such activities inevitably diminished his direct involvement in painting, but he commanded an efficient and flexible crew that included regular assistants, primarily Giovanni Francesco Penni and Giulio Romano, as well as specialist associates such as Giovanni da Udine, the recreator of neo-antique decorative schemes under Raphael’s supervision. Unrestricted in his interests and ambitions, Raphael also designed sculpture, simulated and real, silverware, mosaics and, of course, tapestries.

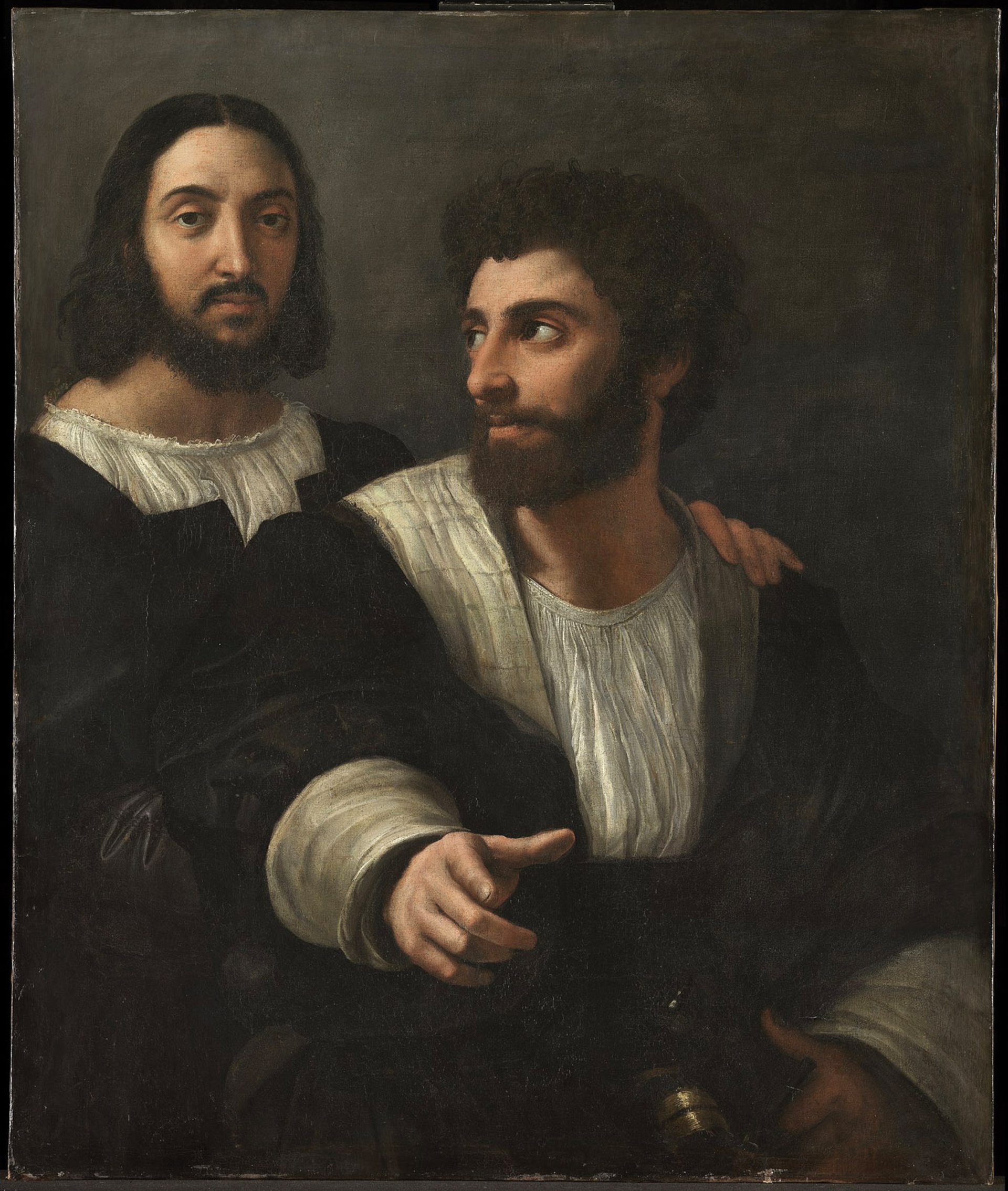

The main stress of the large Quirinale exhibition and catalogue, Raffaello 1520-1483, was on Raphael’s intellectual achievement. Boldly, the exhibition was organised in reverse chronology so the visitor—and reader—was invited to swim upstream from the Roman delta to the Marchigian springs. But, in fact, eight of the 11 chapters concentrate on his Roman work and those dealing with Florence, Umbria and the Marches are slim. That the cover sports Raphael’s Self-portrait of around 1506, not his late Self-portrait with Giulio Romano, is a misleading call sign.

Friends who saw it found the exhibition spectacular and revelatory, with the large ground plans for Villa Madama by the executive architect Antonio da Sangallo and his team—discussion of which comprises one of the catalogue’s strongest chapters—making a powerful impression. Other sections address Raphael and Vitruvius, and his letter to Leo X, in informative essays and entries on specific objects. Raphael’s investigation of antique sculpture, painting and architecture, long the subject of detailed study, notably by Arnold Nesselrath, was evoked by juxtaposition of drawings and objects. And this aspect of the Quirinale show was amplified by an on-site exhibition at the Domus Aurea, whose informative catalogue includes coloured reconstructions of some of the grandest spaces. Reanimating the dulled and damaged surviving fragments, they actualise for the reader the compelling impact of the ancient Domus around 1500.

Claudia La Malfa’s lively book follows Raphael’s developing interest in antique forms in his paintings and drawings. A few translatory sputterings aside, it serves as a readable general introduction to Raphael’s art, for her analyses stretch well beyond the central theme. But the book’s effectiveness is compromised by its production: time and again intriguing relations posited in the text remain unillustrated, while familiar pictures—admirable in themselves but irrelevant to her argument—are unnecessarily reproduced. A telling juxtaposition of a Roman head of Venus and an auxiliary cartoon for Parnassus is nullified by the reproduction of the wrong auxiliary cartoon.

Raphael’s cartoon for Christ’s Charge to Peter (Matthew 16: 18-19 and John 21: 15-17) (1515-16) Photo © V&A. Courtesy Royal Collection Trust Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Raphael’s letter to Leo X, written with The Courtier author Baldassare Castiglione—recently acquired by the Italian State—was the centrepiece of a satellite exhibition devoted to Castiglione held in Urbino, where he and Raphael met. Among the exhibits was a little known canvas from Cremona, which expands Raphael’s lost “bald” head study of his friend, best known in a panel from the studio of Giulio Romano, which was also shown. The dating of Raphael’s great portrait of Castiglione, displayed in Rome but evoked in Urbino by copies—one by Ingres’ pupil Raymond Balze—is contentious: sometimes placed as early as around 1513, it was, with virtual certainty, painted in 1519 at the moment of their closest collaboration. The pensive sitter, saddened by Leo X’s seizure of Urbino, and the exile of the Della Rovere family, is examined with lucid empathy by his friend, whose loyalties would also have been divided.

The Urbino exhibition must have been a delight to visit—enriched with gorgeous reconstructions of early 16th-century costumes plus an array of small bronzes, antiquities and ceramics, mostly from private collections, to evoke Castiglione’s physical ambience. From the illustrations some of these seem to be of high quality but, regrettably, they were not catalogued.

In the Quirinale show Raphael’s art was a secondary consideration, and the catalogue’s treatment of drawings and paintings is unsatisfactory. The various contributors swallow whole the unsubstantiated, method-free pronouncements of Konrad Oberhuber, and disparate drawings and paintings by associates are attributed to Raphael en bloc. The entries’ bibliographies are rather obviously tailored to suppress divergent views, including those of Konrad himself, before his conversion to pan-Raphaelism. In addition to burdening Raphael—sometimes laughably—with works that are not his, those associates’ graphic profiles become utterly confused. Among Raphael’s great strengths as an organiser were his ability to delegate and to involve his collaborators in the creative phases of projects as well as their physical realisation; not to appreciate this is to misunderstand him. We shall have to wait for drawings by Penni, Giulio, Perino del Vaga and Polidoro da Caravaggio to appear on the market as by Raphael to learn how many collectors and museums are persuaded by Konrad’s expansionism.

Much more interesting in its treatment of Raphael’s painting is Nesselrath’s book. Containing five linked meditations on various aspects of Raphael’s work, it teems with novel ideas and observations. Encouragingly, Nesselrath’s discussion of the Raphael équipe diverges from pan-Raphaelism: thus, he gives Justice and Comitas, executed in oil in the Sala di Costantino, to Giulio, in contrast with the Quirinale catalogue, where they become Raphael. Other ideas, such as his attempt to identify Giovanni da Udine as a figure draughtsman, or his insistence on Lorenzo Lotto’s participation in the first two stanze, are less convincing. But notably courageous is his detachment—even from Raphael’s circle—of the Fornarina, which most critics nowadays believe to be an autograph masterpiece. Whether or not Nesselrath’s conjectural reattribution to Annibale Carracci is correct—and it is not obvious to me—coming from so eminent a scholar, it cannot be ignored.

Nesselrath served for many years as a curator at the Vatican and has extraordinary familiarity with its decorative schemes. A bright thread running through his book is Raphael’s intellectual vitality, his spontaneity and capacity for improvisation: abilities apparently unexpected from the super-rational planner. This inspires passages of fine appreciation, enlivened by surprising asides: who would expect a Vatican curator to adduce lesser-known films by Polanski and Borowczyk? But they refresh Raffaello! and point up the comparative timidity of critical analysis and appreciation found elsewhere.

A growth area in Raphael studies, much inspired by the work of Thomas Campbell, has been the master’s involvement with tapestry design. On view at the Victoria & Albert Museum since 1865, the quality of his cartoons for the Sistine Tapestries has always inspired respect but rarely love. The cartoons and tapestries were treated exhaustively by John Shearman in a great, but forbidding, volume of 1972 and, more accessibly, by Sharon Fermor in 1996. But a turning point was the well-lit display of cartoons and tapestries organised at the V&A in 2010-11 by Nesselrath and Mark Evans. Studying the cartoons side by side with a selection of tapestries was revelatory. Compared with the immediately contemporary Stanza dell’Incendio—in which Raphael’s participation was confined to parts of the name piece—it was evident that the cartoons are, as Vasari reported, effectively autograph, demonstrating Raphael’s magisterial control of three-dimensional form, space and atmospheric recession.

Raphael’s Self-portrait with Giulio Romano (1518-20) Photo: E. Lambert

Ana Debenedetti’s book contains excellent essays on the tapestries’ creation, display and history, and valuably updates and expands on Shearman and Fermor; but I would have welcomed a more enthusiastic response to the cartoons’ quality, as well as some discussion of Raphael’s choice of a neo-Masaccesque style. Raphael’s fascination with the antique should not cause us to underestimate his use of his Quattrocento predecessors.

An ancillary revelation of the V&A exhibition was the fidelity of the Mortlake tapestries to the cartoons’ majestic austerity. By contrast, Van Aelst’s weavings, beautiful though they are, dilute form with decoration. The catalogue of the exhibition at Dresden, which owns six Mortlake tapestries, studies their relation to the cartoons with great sensitivity. It also includes several exemplary essays dealing, among other topics, with later political readings of the series and their visual influence—notably on Nicolas Poussin, the painter who best understood them and who matched Raphael in the Pointel Sacraments.

Like the V&A volume, the Dresden catalogue contains essays addressing the issue of the tapestries’ intended placement. In a famous article of 1958, Shearman and John White proposed that the Pauline and Petrine sequences were both ordered, like the narrative frescoes commissioned by Sixtus IV, chronologically—an idea actually due to Lee Johnson, who had worked with them under the tutelage of Johannes Wilde. They placed Paul’s story on the North wall and Peter’s on the South. This arrangement, which Achim Gnann subtly endorses in the Dresden catalogue, has been challenged in recent years by Nesselrath and Anna Maria De Strobel, who have swapped these placings. Their arguments, largely based on their reconstruction of the location of the Sistine’s screen and cantoria, are hard to assess without direct examination of the physical evidence. But it is worth remembering that the Shearman-White layout conforms to the Chapel’s pre-existing illumination, while the new one implies either an error—by Raphael or the weavers—or that the tapestries were deliberately contra-lit. It will be intriguing to see how this debate plays out.

Printmaking has long been the Cinderella of Raphael studies. Much remains to be determined about authorships and dates both of designs and engravings, and a catalogue raisonné of prints by Marcantonio Raimondi and his associates is a pressing desideratum. Naoko Takahatake’s annotated edition of Malvasia’s life of Marcantonio, part of a multi-volume edition/translation of the Felsina, is a significant step forwards.

Like Vasari, Malvasia took Marcantonio’s life as the starting-point for a larger project: in his case a listing of prints made by Bolognese artists from around 1500 to his own times, a body of work surveyed in 900 illustrations. But on Marcantonio himself Malvasia added little to Vasari, whom he followed sometimes to the point of plagiarism; his attributions are not always reliable, and he makes little use of dated prints. Malvasia’s real value is that he measured and described in detail a selection of prints that Vasari only mentioned and thus established a foundation for Mariette and Bartsch. Takahatake’s book is a valuable addition to the literature and all students of Marcantonio will need it: but cross references to Vasari’s listings and vols. 26-29 of The Illustrated Bartsch would have enhanced its utility.

Marco Bussagli, Raffaello. Nella pittura un dio mortale, Giunti Editore, 319pp, €85 (hb)

Barbara Agosti and Silvia Ginzburg, eds, Raffaello e gli amici di Urbino, Centro Di, 288pp, €40 (pb)

Timothy Wilson and Claudio Paolinelli, Raphael Ware. I colori del Rinascimento, Umberto Allemandi, 288pp, €60 (pb)

Marzia Faietti, Matteo Lafranconi et al, Raffaello 1520-1483, Skira Editore, 544pp, €46 (hb)

Claudia La Malfa, Raphael and the Antique, Reaktion Books, 304pp, £16.95 (hb)

Vittorio Sgarbi and Elisabetta Soletti, Baldassarre Castiglione e Raffaello. Volti e momenti della vita di corte, Maggioli Editore, 209pp, €15 (pb)

Arnold Nesselrath, Raffaello!, Mondadori Electa, 223pp, €99 (hb)

Ana Debenedetti, ed, The Raphael Cartoons, V&A Publishing, 112pp, £9.99 (pb)

Stefan Koja et al, Raphael. The Power of Renaissance Images: the Dresden Tapestries and their Impact, Sandstein Verlag, 336pp, €48 (hb)

Carlo Cesare Malvasia with Naoko Takahatake, ed, Felsina Pittrice. Lives of the Bolognese Painters. Volume Two, Part Two, Life of Marcantonio Raimondi and Critical Catalogue of Prints by or after Bolognese Masters, Harvey Miller Publishers/Brepols, 2 vols, 844pp, €300 (hb)

• Paul Joannides is the Emeritus Professor of Art History of the University of Cambridge