Archaeologists excavating at La Almoloya, Spain, have discovered a grave filled with precious items and the remains of a woman, who may have been a ruler or powerful member of society. The woman was buried alongside a man in a large pot in around 1700 BC, beneath the floor of what may be western Europe’s earliest palace.

The majority of the grave’s objects, and particularly those of silver, were found with the woman, including a rare silver diadem, still worn on her head. Scholars argue that this was a symbol of power in El Argar society, which existed in south-eastern Spain from around 2200 to 1550 BC. Among the woman’s other grave goods were a set of silver earlobe tunnel-plugs; silver spirals that were perhaps part of her headdress; two silver bracelets; a necklace; and a silver ring on one of her fingers. In total, the burial contained about 230g of silver. The man’s objects, by contrast, were less prestigious.

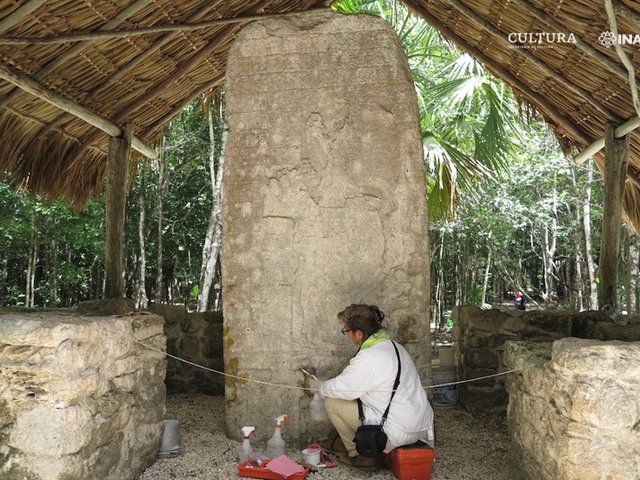

A selection of the grave goods found at the site in La Almoloya, Spain Photo: J.A. Soldevilla, courtesy of the Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrània Research Group, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Four other Argaric silver diadems, of the same type as that found at La Almoloya, have previously been discovered at another site, all in the graves of women. “The value and function of the emblematic goods surrounding this woman, as well as the four other women found with a silver diadem, suggest that they were political and economic leaders in their own right, and not just the partners of ruling men,” says Roberto Risch, a professor in prehistory at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and one of the authors of the study, published in the journal Antiquity.

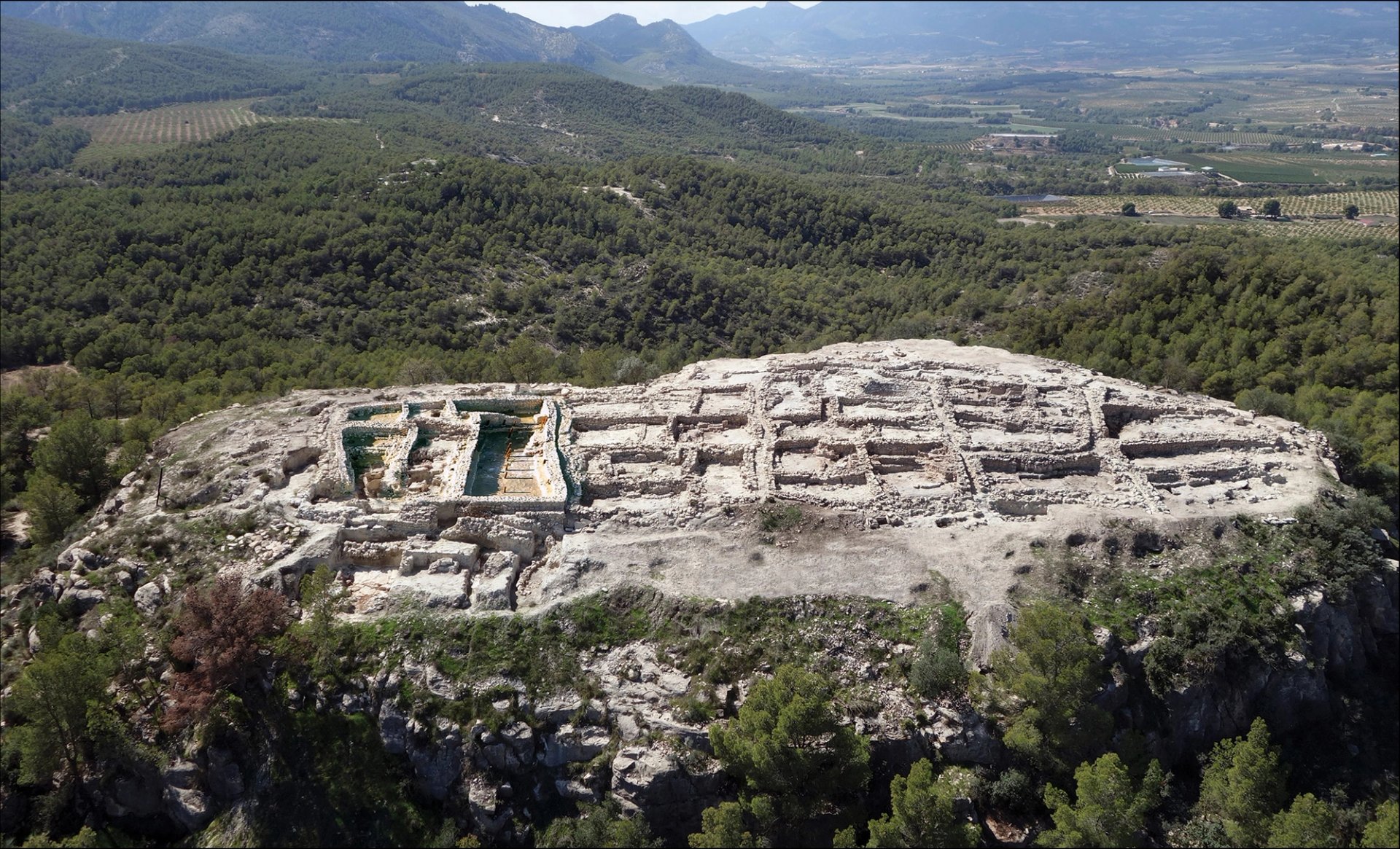

The grave was found beneath the floor of La Almoloya’s largest room, itself part of a monumental building that may have been a palace. Benches lined this room, providing space for around 50 people. “The absence of drinking vessels or food containers and remains, as well as of ritual objects in the hall, implies that the people meeting here were mainly communicating with each other, or attending to someone,” Risch says. “The placement of one of the wealthiest burials of the European Bronze Age in this unique room is a hint of who was in control of such communicative practices.”

Aerial view of La Almoloya in 2015 Photo: courtesy of the Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrània Research Group, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Leonardo García Sanjuán, a professor in prehistory at the University of Seville says that “this new research connects well with previous knowledge about Bronze Age ‘Argaric’ society, while at the same time provides fresh evidence and important new interpretations.” But he also notes that the socio-political organisation of Iberian Bronze Age society is a controversial topic within Spanish archaeology. “In my opinion, it would be premature to portray this woman as a ‘ruler’ or even less as an ‘aristocrat,’ as these terms convey strong assumptions regarding the nature of the society she was part of,” Sanjuán says. He adds, however, “that she was a powerful woman in her time is beyond doubt.”

Archaeological discoveries about Argaric society “unveil how rudimentary our visions and understanding of prehistoric societies really are,” Risch says. “Until a few years ago, when our project started, no one imagined the scale of the El Argar architecture nor of the wealth stored in these truly urban settlements.” This society had been ignored for a long time, he says, and “probably represents the last ‘lost civilisation’ in Europe”.