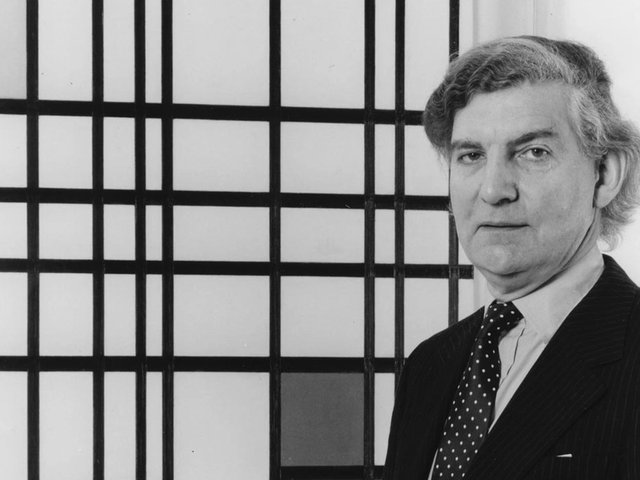

Alan Bowness was an art historian whose eye and influence shaped the British contemporary art world over more than 40 years. He never sought the limelight, but his quiet self-assurance and belief in his own convictions inspired confidence in others and made him the most persuasive and effective voice in a talented post-war generation of curators, writers and critics.

In the late 1950s and through the 60s and 70s, he was a pioneering academic and a friend to a generation of abstract artists in England, whose work he championed in print and in the many committees on which he served. In the 80s he became a more public figure as the director of the Tate Gallery, where he made important acquisitions for the national collection, achieved a resolution of the long-running debate about how to honour J.M.W. Turner’s magnificent bequest to the nation and established a new northern outpost for the gallery in creating Tate Liverpool. In the 90s and beyond, he continued his patronage as the director of the Henry Moore Foundation and administrator of the estate of Barbara Hepworth, encouraging the study and exhibition of sculpture in the county of their birth through his creation of the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds and his advice and support for the development of The Hepworth Wakefield.

As a schoolboy at University College School in Hampstead, north London, he had developed an interest in the arts and in politics, discovering the writings on art and anarchy of Herbert Read, the critic and friend of Moore, Hepworth and Nicholson. In 1945, at the age of 17, he found his interest in painting further sparked by seeing the legendary Picasso and Matisse exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. He began to look at contemporary British art, including Moore, Sutherland, Hitchens and Pasmore, which he found in Kenneth Clark’s series of Penguin Modern Painters books and in the Bond Street galleries. However, this burgeoning interest had to be set to one side when, as a young conscientious objector who had been appalled by the bombing of Dresden, Bowness chose to serve for a period of four years with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit and Friends’ Service Council in England, Germany and Lebanon rather than undertake National Service in the military.

As a student at Downing College, Cambridge, he extended his engagement in the visual arts, visiting the Fitzwilliam Museum and taking on responsibility for running a picture-lending scheme for undergraduates, an activity that gave him the opportunity to meet painters such as Ivon Hitchens and Keith Vaughan. It was Carl Winter, the director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, who encouraged him to follow this interest by undertaking postgraduate studies in art history at the Courtauld Institute. In his second year, he chose to study the “Modern” period, covering the late 18th to the early 20th century, from David to Picasso, which was taught by the Courtauld's director, Anthony Blunt, who Bowness regarded as an inspiring teacher.

On leaving the Courtauld in 1955, he began to write book and exhibition reviews for the fortnightly Art News and Review and from then until 1963 he was also a contributor to The Observer. This was a moment of profound change in the contemporary art world with New York beginning to replace Paris as the principal centre for advanced painting and sculpture. As a writer on contemporary art, Bowness increasingly found himself drawn towards abstraction and away from the international social realism being promoted by John Berger and the British realism of “Kitchen Sink” as it was called by David Sylvester, both of whom were very slightly older contemporaries.

In the late 1950s and through the 60s and 70s he was a pioneering academic and a friend to a generation of abstract artists in England, whose work he championed in print and in the many committees on which he served

Early in 1956, Bowness was appointed as a Regional Art Officer at the Arts Council with responsibility for advising on grants to artists and taking Arts Council exhibitions to museums and galleries in the South West. In April 1956, he visited St Ives, which had become the one centre of artistic production that could rival London. Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth had been working there since 1939 and by the mid-50s, Nicholson was at the peak of his international reputation while Hepworth was beginning to make work of a scale and ambition that would soon bring her similar international recognition. A younger generation was also emerging with Peter Lanyon making expressive abstract paintings that grew out of his feeling for the ancient West Penwith landscape and Patrick Heron venturing beyond an initial abstract moment inspired by the garden at his home, Eagles Nest, into abstract colour compositions reflecting his experience of the light of West Cornwall.

These encounters confirmed the direction of his own thinking and Bowness became increasingly committed to the principle of abstraction, not as dogma but as a matter of personal preference. It is the same sensibility that drew him to feel a special affinity with 20th-century and contemporary music and made him a regular member of the audience at recitals at the Wigmore Hall and elsewhere until the lockdown closed concert halls last year. The visit to St Ives changed his life in another sense. The following year he married Sarah, one of the daughters of Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, thereafter returning each year to Cornwall.

Bowness with his wife Sarah Hepworth-Nicholson in Barbara Hepworth's garden, Trewyn Studio, St Ives, c.1958

Bowness with Barbara Hepworth, his mother-in-law, September 1964. On a boat from Copenhagen to Sweden to visit Dag Hammarskjöld’s Museum © Bowness

In 1957, he was invited by Anthony Blunt to teach the European Modern period course at the Courtauld. At the time art history was still in its infancy as an academic discipline and the Courtauld was the only university in England that offered the opportunity to study a period and artists that were still not fully recognised as being worthy of deep research. However, its reputation was growing and under Blunt it attracted talented, dedicated students, to whom Bowness devoted his attention. He discovered that he liked teaching and his students liked him. Years later, after he left the Tate, he would say that he was “temperamentally… a teacher, preacher… more than an administrator”. He established a course that offered the opportunity to study the 19th century from the realism of Courbet and Revolutions of 1848, initially to the Cubism of Picasso and Braque before the First World War and later to Surrealism before the Second World War. For Bowness it was the works themselves rather than the social and political context that were paramount.

As a teacher, Bowness encouraged close readings of the work and of the intentions of the artist

Bowness taught many of the art historians who subsequently went on to head university departments across the country and to lead museums both in Britain and abroad

In the tradition of F.R. Leavis, he believed that “art displays its meaning best when directly confronted—an idealist attitude, but one to keep in mind”. He encouraged close readings of the work and of the intentions of the artist, a form of art history that came to be challenged in the eighties by historians who argued that social, political and historical context should be given more weight. Over the years, Bowness taught many of the art historians who subsequently went on to head university departments across the country and to lead museums both in Britain and abroad. He took a close interest in their careers, ensuring that they would prosper through his very wide network of contacts, and he steadily built the reputation of the department, bringing in distinguished scholars like John Golding and Christopher Green (a former student) alongside him.

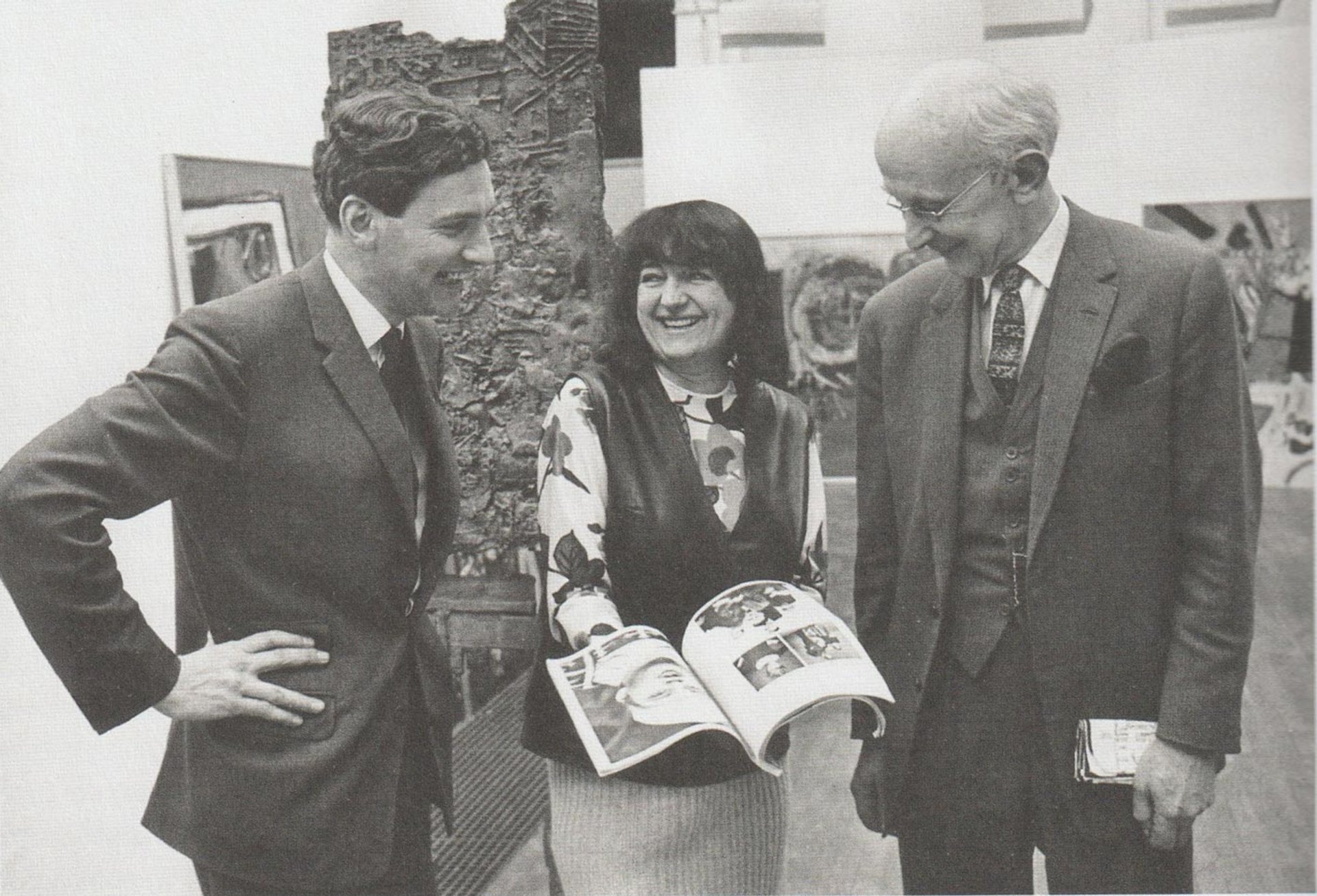

In 1960, Bowness was invited to join the Art Panel of the Arts Council. At that time the Arts Council not only funded galleries and artists, but also undertook the organisation of major exhibitions in London, primarily at the Tate Gallery and in a small gallery at its office in St James’s Square, as well as an active programme of exhibitions touring to regional galleries. It was also building a collection of contemporary British art in support of artists and for showing in regional galleries. The council was therefore an immensely influential force in the contemporary art world. Shortly afterwards he also became a member of the Fine Arts Advisory Committee at the British Council, which promoted British art overseas. Bowness, a respected academic and regular contributor to The Observer, married to the daughter of two of the most prominent British artists, found himself at the centre of power and began to become involved in the organisation and curation of exhibitions as well as writing catalogue introductions. He identified, personally, with the abstract painters of St Ives and with the tradition of constructivist art that had been embraced by Victor Pasmore, Anthony Hill and Kenneth Martin, amongst others. However, as the decade moved forward, he adopted a more catholic position, taking an interest in the emerging forces of contemporary abstract painting and sculpture exemplified by Riley, Hoyland, Smith and Caro and by the second generation associated with Pop—Hockney, Kitaj, Jones, and Blake. From the early sixties he was regularly a curator of Arts Council and British Council exhibitions. In 1964 he co-curated with the painter and historian Lawrence Gowing a major survey, funded by the Gulbenkian Foundation and shown at the Tate, of international art of the previous decade. 54/64 was widely recognised as a landmark exhibition, far more ambitious in its scale and range than was then customary.

Ambitious in scale and range: Alan Bowness (left) with the architect Alison Smithson and Philip James—former Director of Art at the Arts Council—during the installation of the Painting & Sculpture of a Decade: ’54-‘64 exhibition at Tate, 1964. From Lisa Tickner’s book London’s New Scene (Yale, 2020) Smithson Archive © Smithson Family Collection

As a member of the Art Panel, and twice of the Council itself, Bowness exercised tremendous influence on the Council’s policy on the visual arts. From the mid-60s, he was largely responsible for the increasing financial support that the Council gave to galleries in the regions that were showing contemporary British art. Galleries without collections, like the Arnolfini in Bristol, the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, or the Midland Group in Nottingham, as well as the Whitechapel in London, were often led by strong individuals and run by independent trusts rather than by local authorities and Bowness believed that this gave them greater freedom to show new work and support living artists.

Throughout this period Bowness continued to teach at the Courtauld. He published respected popular books on Modern Sculpture (1965) and Modern European Art (1972) and made steady progress in his role as editor of successive volumes of the Complete Sculpture and Drawings of Henry Moore. He published definitive books on the work of William Scott, Ivon Hitchens, Alan Davie and Barbara Hepworth. He also curated major exhibitions relating to his academic work, including van Gogh in England (1969), Rodin (1970), French Symbolist Painters (1972), the Impressionists in London (1973, to mark the UK’s accession to what became the European Union) and Courbet (1978). In 1979, he assembled a team of former students and colleagues from the Courtauld to mount Post-Impressionism, a scholarly and immensely popular exhibition at the Royal Academy and National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

In 1980, he was the natural choice to be Director of the Tate Gallery. Bowness had been a candidate in 1964 when Norman Reid was appointed, but at 36 had been thought too young. Inheriting a strong staff, many of whom were personal friends, Bowness set out to build the Collection, to take advantage of an opportunity to create a home for the Turner Bequest, to extend the reach of the Gallery beyond London and to engage with a new generation of artists.

His predecessor had negotiated a significant increase in the Purchase Grant and Bowness immediately sought to strengthen the collections of Modern European and American Art as well as balancing the perceived leaning towards abstraction in recent purchases of contemporary British art. Over the period of his directorship acquisitions of major works by Dalí, Picasso, Ernst, Miró, de Chirico, Picabia, Magritte, Schwitters and Beckmann transformed the representation of European art between the wars. The collection of post-war Art was also immensely enhanced by judicious acquisitions of School of Paris and Cobra painters as was the representation of Abstract Expressionism with fine examples by Newman and Pollock joining the collection. He acquired a major Warhol, the Marilyn Diptych, and important works by Jasper Johns, Philip Guston and Willem de Kooning. He was also determined that established British artists should be seen in depth and acquired major works by Bacon, Hockney, Kitaj, Auerbach and Freud as well as an emerging generation of sculptors such as Cragg, Gormley, Wilding, Deacon and Kapoor.

In 1979, Vivien Duffield, the daughter of the the retailer, financier and philanthropist Charles Clore, offered a gift that would facilitate the creation of a new gallery to house the Turner Bequest, which had been divided between the Tate (paintings) and the British Museum (drawings and sketchbooks) following the Thames flood of 1928. The success of the bi-centenary exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1975 had led to a campaign to re-unite the bequest, but government had been unwilling to cover the cost. In 1978, the trustees had appointed the architect James Stirling as architect to advise on the development of the neighbouring “Hospital” site that had been given to Tate for expansion in 1969. It was therefore natural that Stirling should be invited to design the building for the Turner Bequest and fortunate serendipity that Bowness and Stirling had known each other for many years. Bowness was dismayed that such an outstanding Modernist architect had received so few commissions in England in the previous decade and was realising his major buildings in Germany where he was at work on the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart amongst other projects. The Clore Gallery opened in 1987 and became the first in what Bowness and Stirling conceived as a “cluster of art museums, each with a separate collection and distinct architectural character” situated around a courtyard behind the Clore Gallery. These were intended to house different parts of the Tate Collection, including “modern sculpture”, “new art”, “a study centre for the archive and library” and a “museum of the 20th century”. However, these plans were superseded in 1992 by the trustees’ decision to create Tate Modern at Bankside.

Stirling and Bowness also worked together on the second major expansion project of the Bowness era, Tate Liverpool. In the mid-70s, as the Tate was beginning to contemplate the development of the “Hospital” site, Stewart Mason, a trustee and former Director of Education in Leicestershire, had argued that it would be wrong to build more in London without sharing the collection with the rest of the country. He was supported by the Chair, the historian Lord Bullock, who was a Yorkshireman, and the idea of a “regional satellite” was born. In 1979, the trustees agreed to take on responsibility for the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden in St Ives, which had opened as an independent museum shortly after the sculptor’s untimely death in 1975. On his arrival, Bowness, who had been closely involved with the creation and transfer of the Hepworth Museum as executor of the sculptor’s estate, enthusiastically adopted the idea of further “outstations” and began to look for a suitable location to create a “Tate in the North”.

In the spring of 1981, the riots in Toxteth led the Thatcher government to create the Merseyside Development Corporation at the initiative of Michael Heseltine, Secretary of State for the Environment. One of the corporation’s first priorities was the renovation and regeneration of Jesse Hartley’s magnificent Albert Dock and Bowness immediately recognised that it would be “the right place” for the regional outpost. Stirling had grown up in Liverpool and the combination of majestic 19th-century brick architecture and Stirling’s increasingly post-modern vocabulary appealed to Bowness. With the support of his assistant Edwina Sassoon, Bowness raised the £2m that was required to fit out the building that had been essentially renovated by the Corporation and the Gallery opened to immense applause shortly before the end of his directorship.

A man whose moral authority and quiet advocacy brought attention to a generation of British artists, whose teaching inspired students who have in turn shaped the course of art history in the succeeding forty years

In the early 80s the advent of the Thatcher government brought about profound changes in the way in which national museums like the Tate were expected to function. With no significant increase in public funds, they were now expected to reach out to the business sector to secure sponsorship for exhibitions and to foundations and individuals for donations to support acquisitions, educational and building projects. Bowness was philosophically opposed to this move, believing that it was the duty of government to sustain free museums for the benefit of a wide public, and furthermore he was temperamentally unsuited to taking a leading role as a fundraiser. However, he set out to do his best for the Tate and was remarkably successful, securing the funds for Liverpool, sponsorship for exhibitions and in establishing groups of Patrons whose contributions made it possible to acquire “New Art” and “British Art” for the Collection. He also established the Turner Prize in 1984 as a way of generating greater interest in contemporary British art.

It was therefore surprising when he came under fire from the chairman-elect, Peter Palumbo, in an interview in a Sunday newspaper in 1984. Palumbo exposed the impatience of a group of trustees who felt that the pace of change at Tate was too slow and that opportunities were being missed to purchase important works of art. Although Bowness, supported by his chair, Lord Hutchinson, obliged Palumbo not to take up the role and to give way to Richard Rogers, the incident created a small cloud over his final years, notwithstanding his knighthood in 1988 and the successful opening of the Clore Gallery and Tate Liverpool.

Bowness: moral authority and quiet advocacy Gautier Deblonde

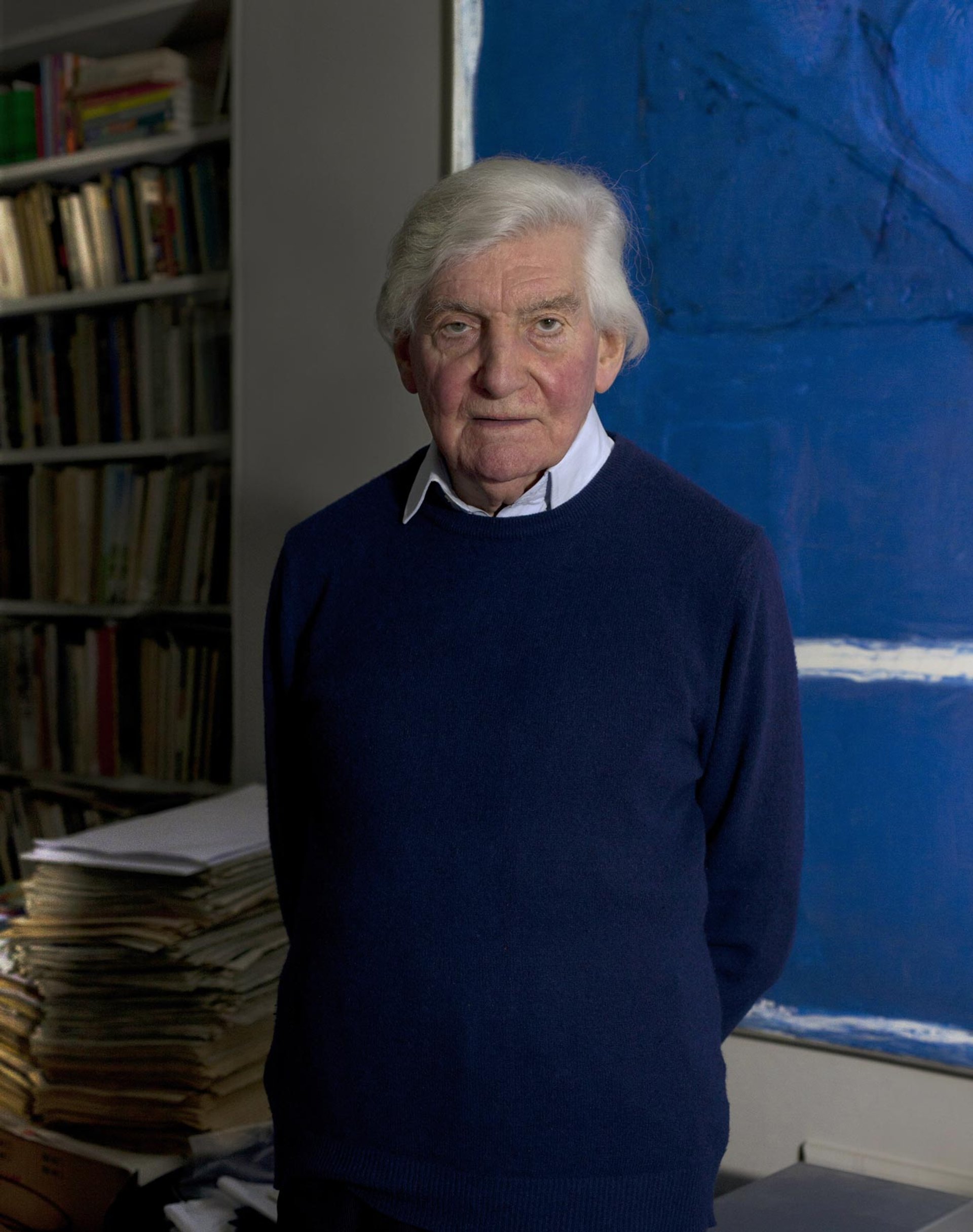

On leaving the Tate in 1988, Bowness became the director of the Henry Moore Foundation, established by Moore in 1977 to care for his work and legacy and to offer grants to exhibitions and projects that advanced the study of sculpture of all periods. Bowness saw an opportunity to build on an earlier commitment to Moore by Leeds City Art Gallery by establishing a Henry Moore Institute for the study of sculpture on a site alongside the Gallery. Designed by architects with whom Bowness had worked at Tate and who were then building the extension to the Royal Opera House—Jeremy Dixon and Ed Jones—the building houses an academic study centre and archive and has produced an impressive sequence of small exhibitions devoted to all periods of sculpture. Having retired from the Henry Moore Foundation in 1994, Bowness continued to devote his attention to the Hepworth estate, working closely with his daughter, the art historian Sophie Bowness, on the catalogue raisonné, other publications, exhibitions and placing works by Hepworth in important collections. They also made a decision to support the creation of the museum in Wakefield that bears her name, making a major donation of plasters by the artist to ensure that her work can be seen in strength in the city of her birth. The Hepworth Wakefield, designed by David Chipperfield, opened to great acclaim in 2011.

During his most active years as a writer and curator, Bowness acquired works from the artists with whom he was working by a combination of gift and purchase. In 2016 Downing College, of which he was an honorary fellow, presented an exhibition focused on the largely abstract works that he had collected in the period 1955-65, many of which are destined for the Fitzwilliam Museum and other public collections, while his library will go to the Cambridge University Library. Together these works and such gifts disclose the character of a man whose moral authority and quiet advocacy brought attention to a generation of British artists, whose teaching inspired students who have in turn shaped the course of art history in the succeeding forty years, and whose leadership of the Tate took it beyond London and into a world where contemporary art plays a larger part in the lives of people than could have been anticipated 50 years ago. Alan Bowness played a decisive role in promoting that change.

- See also the obituary of Alan Bowness by Richard Calvocoressi.