On the first anniversary of Mark Fisher’s death, aged 48, in January 2018, his students, colleagues and friends celebrated the life of the influential cultural theorist and academic by throwing a 300-person party.

Since then, For k-punk—named after Fisher’s online alias and blog—has become an ongoing tribute event, organised by students at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he taught. DJ sets by UK-based creatives—last year’s edition included the artist Mark Leckey—mourn one of the pre-eminent voices of the radical left, who took his own life after a well-documented struggle with depression.

Mark Fisher in 2014 © Paul Samuel White

This year, due to Covid-19, For k-punk has moved online, incorporating a new visual element, and now stretches over an entire month thanks to a film commission by the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (ICA). Six musicians and visual artists were invited to respond to themes in the recently published Postcapitalist Desire (2020), which transcribes Fisher’s final lecture series for his MA contemporary art theory course at Goldsmiths.

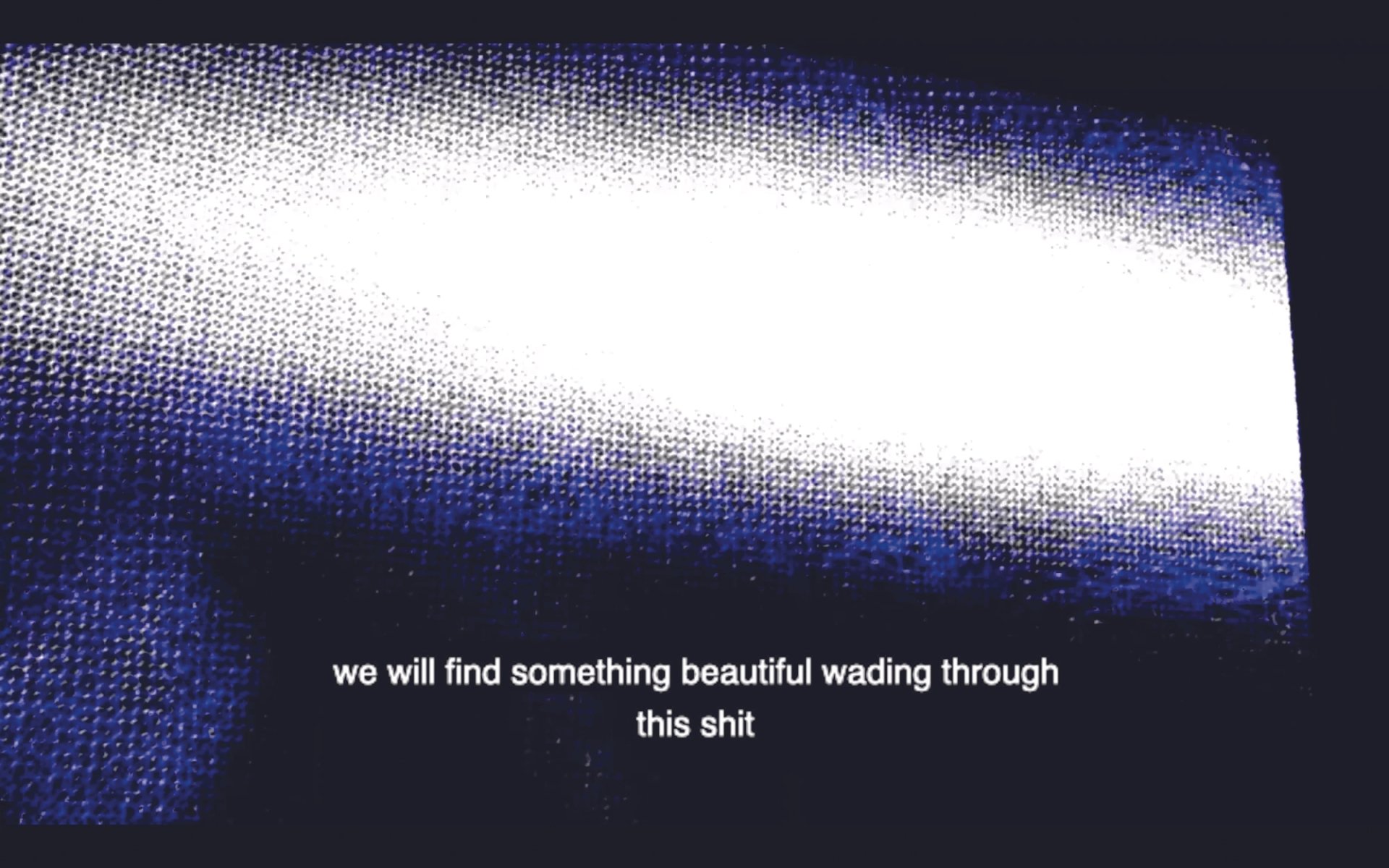

Each of the five sections is a different artist’s response to a specific lecture. They merge, among other things, historic recordings on women’s liberation, electronic dance and ambient music and psychedelic visuals to broach topics like the patriarchal ideal of the family and class consciousness under late capitalism.

This nearly five-hour-long “digital afterparty” is “part virtual club night, part lecture and an expression of collective grief”, says the writer Matt Colquhoun, who edited Postcapitalist Desire and, along with the textile artist Natasha Eves, organises For k-punk. “We debuted it at 10pm to mimic a club night and held a discord server with all of our friends. It was the closest thing we’ll get to a gig for a while,” Eves says. Both were students of Fisher’s at the time of his death—For k-punk commemorates a teacher who “really gave a shit”, they say.

Sweatmother provided the visuals for the film series © ICA London / K-punk

In their response to a lecture on queer desire and the post-modernist philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, the musician IceBoy Violet remixes both Rihanna’s Diamonds (2013) and a track by the dubstep pioneer Burial, of whom Fisher wrote extensively. Accompanying are bellowing revolutionary phrases and shifting graphics of dancers and lattices collapsing in on each other.

“This felt very true to Mark, this synthesis of several creative disciplines into a cohesive, embodied whole,” Colquhoun says.

Fisher’s writing was notable for its breadth of cultural subjects, wedding theory with excoriating critique of popular culture: the German idealist philosopher Hegel would be invoked in the same text as the Disney Pixar movie WALL-E and Damien Hirst (whom Fisher referred to as “a house artist to the 1%”).

Electro-libidinal parasites

Even more fitting is the event’s move online. Fisher began his career writing about late-1990s internet culture and was enthralled by the possibilities of cyberspace. Although wary of the pervasive hyper-stimulation of modern digital life (Fisher called iPhones “electro-libidinal parasites”), he often made the distinction between social media and data-grabbing search engines, and the unindexed, unmonitored expanse of the cyber realm. Accordingly, the visuals and captions unifying the five sections, designed by the filmmaker and artist Sweatmother, are “influenced by early internet aesthetics and 1990s cyberpunk, merged with reworked empty promises of advertisements”, Sweatmother says.

The films are based off Fisher's final lecture series, transcribed into the book Postcapitalist Desire © ICA London / K-punk

Fisher is best known for his 2009 bestselling book Capitalist Realism, based on the idea that in the early 21st century it was easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

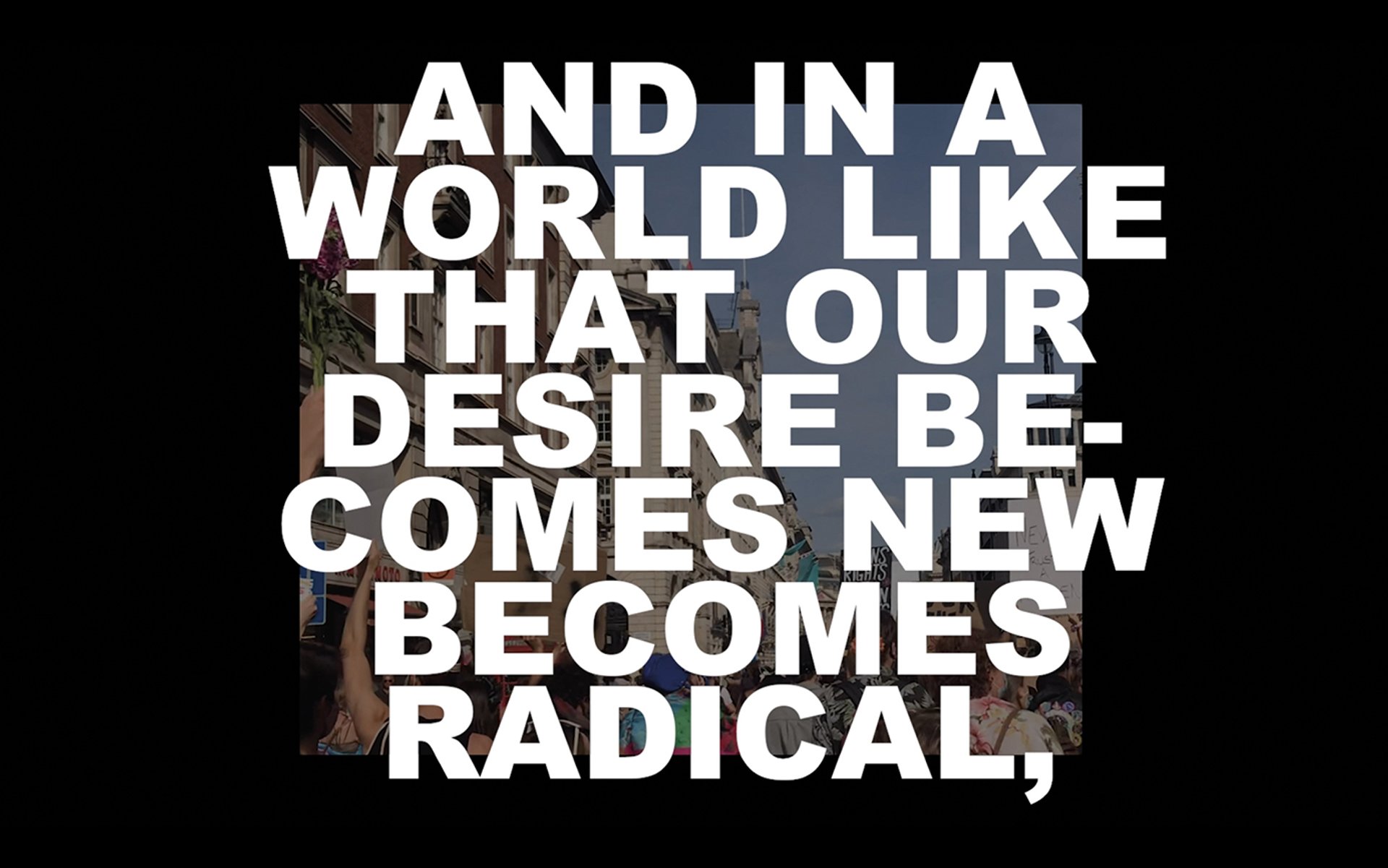

At the time of his death, Fisher had begun Acid Communism, the opening of which features in a posthumously published collection. Here, Fisher sketched plans for a beguiling, utopian project that promises to reclaim a lost future envisaged in the 1960s and 1970s, when he believed that true alternatives to capitalism last existed. This is based, in part, on the practice of “consciousness raising”, an activist tool used by feminists in the mid-20th century—defined by Colquhoun as “collective discussion that highlighted the inequalities under which people collectively lived”. This contrasts with “consciousness deflation”, which Fisher saw as a side-effect of capitalist realism and its neo-liberal push for an unequal and atomised society.

An often unpredictable writer, the Fisher found in later works can appear contradictory. For instance, a sudden willingness to embrace 1960s counter-culture jars against his previously expressed distaste for hippie culture and what he once termed its "hedonic infantilism". Indeed, many of the ideas presented in his final lectures appear inchoate and intentionally provocative, having not yet been developed into fully formed theories. In exploring them, these films may blur neater and more reductive understandings of the writer.

“We are not the definitive annual Mark Fisher event,” Colquhoun says. “There are many Mark Fishers to many people. We didn’t want this to be a prescriptive reading of who he was, but rather a generative space. We’re interested in making space for and sticking to unpredictability, like Mark did when he blogged. It’s ensuring that what we’re doing responds to the topics Mark spoke about in the current moment rather than who Mark Fisher was in 2007.”

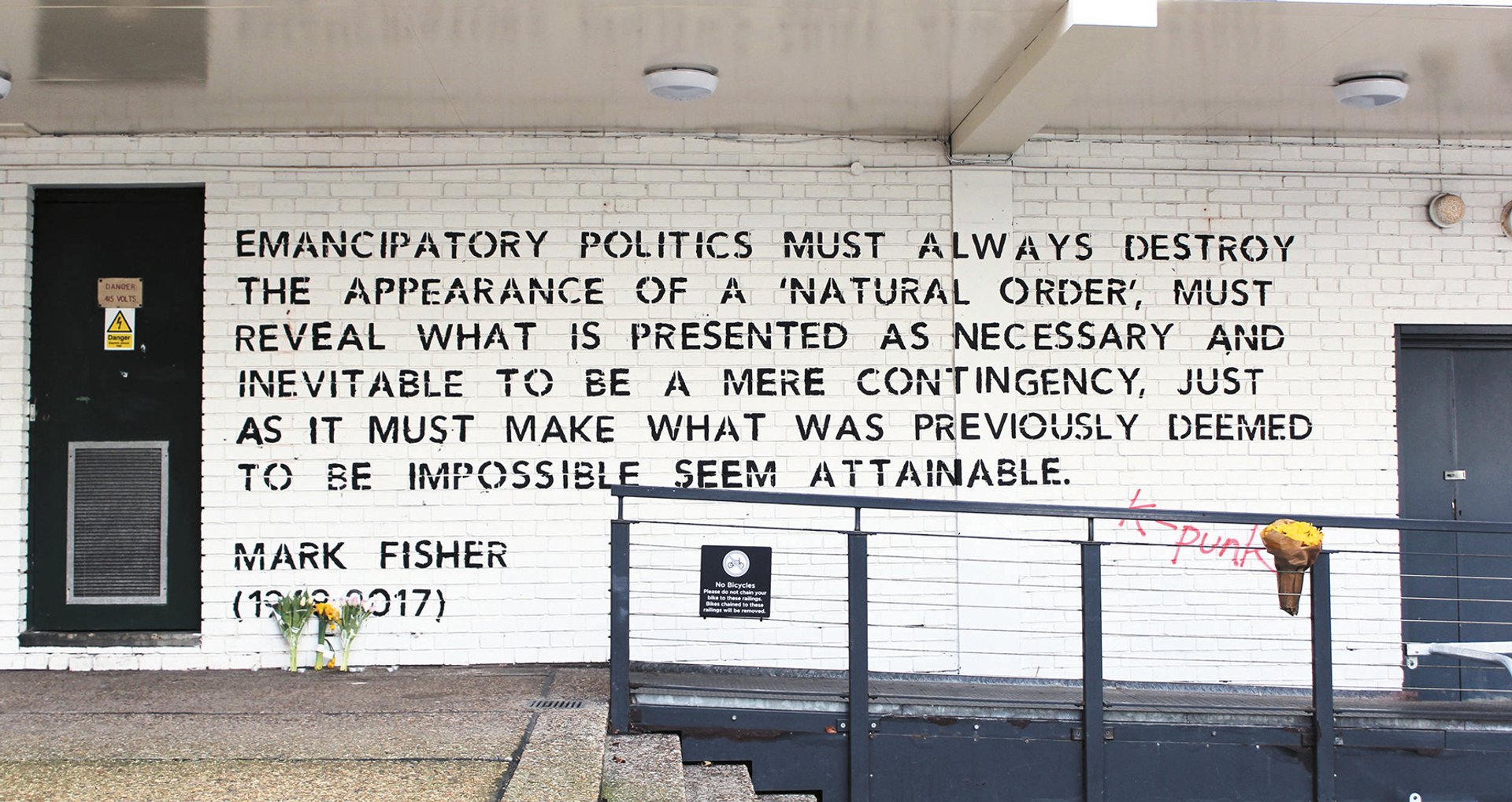

The Marsh Fisher memorial mural at Goldsmiths University, London

In a 2018 memorial lecture, the philosopher Robin Mackay questioned what it means to continue the “abstract force” of Fisher’s thoughts in the present tense—the “Fisher Function”, as he termed it. How might we use his ideas at today’s great political junctures? For instance, how might Fisher’s insistence that personal health problems are usually symptomatic of state policy failure (as he argued of his own depression) fare in the post-coronavirus era?

In the film's penultimate section, the musical duo Incursions (also former Fisher students) respond to a lecture in which Fisher discusses consciousness raising, incorporating excerpts from previous For k-punk nights, emphasising the community that has been built and sustained in Fisher’s absence.

“Real wealth is the collective capacity to produce, care and enjoy,” Fisher wrote in 2015, signalling that the ability to escape capitalism lies well beyond the individual imagination. In theory and practice, the ICA’s project fittingly suggests that only in our capacity for collective action and empathy can we achieve what Fisher was so desperate for: to reclaim political agency and build towards a more joyful and equitable future.

• The ICA in London is hosting For k-punk 2021: Postcapitalist Desires 2021 on its website until 28 February. Free for members. Mark Fisher, Postcapitalist Desire, Repeater Books, 264pp, £12.99 (hb with ebook).