A trickle of intrepid visitors made their way through the various venues of the Outsider Art Fair in New York on its VIP preview day yesterday. In addition to online viewing rooms, this year’s edition of the cult fair is taking place across four galleries in Manhattan, as well as the legendary Electric Lady recording studio, with two solo exhibitions and five broadly themed group exhibitions.

“It would have been easy to roll over and do just the OVRs but we’re scrappy, we’re sort of the renegade fair,” says Andrew Edlin, the fair’s owner, who is hosting one of the group exhibitions in his gallery and notes that the in-person exhibitions offered another low-cost opportunity for participating galleries. “The fair exists for our dealers and we want them to stay in the game until this all blows over.”

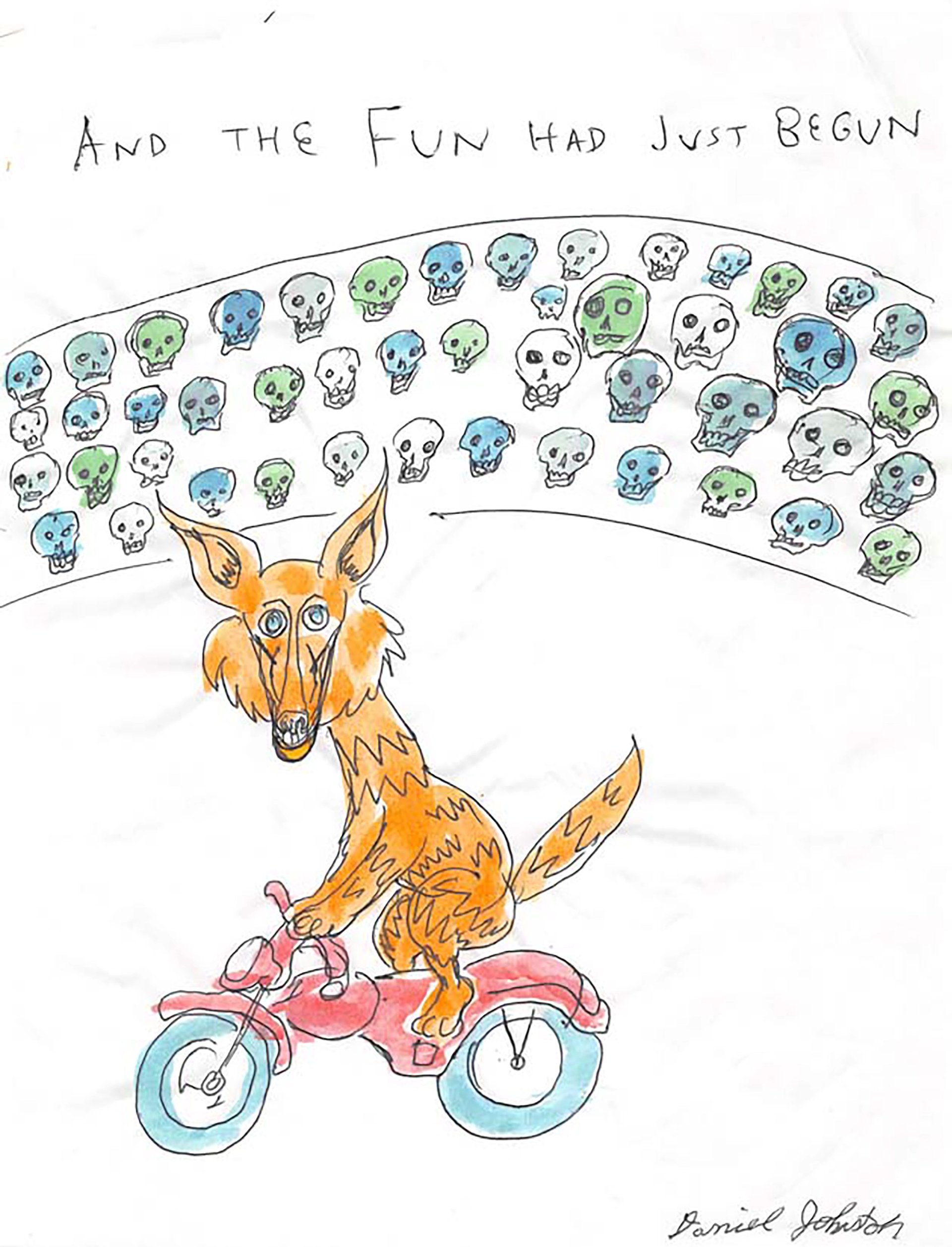

And The Fun Had Just Begun (1999) by Daniel Johnston, part of a show of the artist's Psychedelic Drawings curated by Gary Panter at Electric Lady Studios Courtesy of The Daniel Johnston Trust

Among the highlights, a selection of cartoonish drawings penned by the late musician and artist Daniel Johnston is on view at Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studio, which also offers its own visual treats, including Lance Jost’s lavish, psychedelic wall murals. Johnston’s illustrations (all around $3,500–$5,000) are wired, often very funny, and sometimes quite painful. In one, a horned devil sits in an armchair and reads the daily news. In another, a drawing of his trademark extraterrestrial frog takes the form of a public service announcement declaring that the artist has been imprisoned in a mental hospital. Johnston, who suffered from manic depression, spent some five years of his life institutionalised.

Elsewhere, Salon 94 is showing a selection of work by Aboriginal and outsider artists from Australia and New Zealand. Three gorgeous paintings by Yukultji Napangati and Mantua Nangala—all priced at $55,000—dominate the space. They are composed of serial dots and lines in luminous fields of paint that look like aerial views of abstracted, textured landscapes—they refer to the indigenous artists’ ancestral lands. Nearby, in a strangely resonant pairing, Alan Constable’s wobbly ceramic cameras and optical devices, each going for around $2,000-$3,000, seem to invite holding them up to Napangati and Nangala’s paintings to better see into their depths—but also suggest other, non-optical forms of vision. (Constable is legally blind.)

Installation view of Figure Out: Abstraction in Self-Taught Art, on view at Andrew Edlin Gallery as part of the Outsider Art Fair 2021 Photo: Olya Vysotskaya

Several artists make repeat—and welcome—appearances across the fair, including the labyrinthine abstractions and stream-of-consciousness pencil wanderings of Susan Te Kahurangi King ($8,000–$14,000); the jewel-like landscapes of Frank Walter ($4500–$6,500); the mesmerising geometries of the Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers (around $40,000); and the pioneering works of Janet Sobel ($12,350), a housewife who made all-over painting ahead of Jackson Pollock and who will feature in an upcoming exhibition of women in abstraction at the Pompidou in Paris.

The fair came together in a matter of weeks, Edlin says, on the heels of its “relatively successful” Paris edition in October, which followed a similar hybrid format. He notes that this year’s exhibitor list includes some 45 dealers, down from the 63 or so that normally participate in the fair. Among those notably absent: several of the workshops that support artists with disabilities, which didn’t have the capacity to organise OVRs amid all the challenges of the pandemic. But the thriftiness and intimacy of the showcase make it a model that could stick in a post-Covid world. Tom Parker, associate director of one of the fair’s host galleries, Hirschl & Modern, says he and his colleagues were “very keen” on the hybrid model.

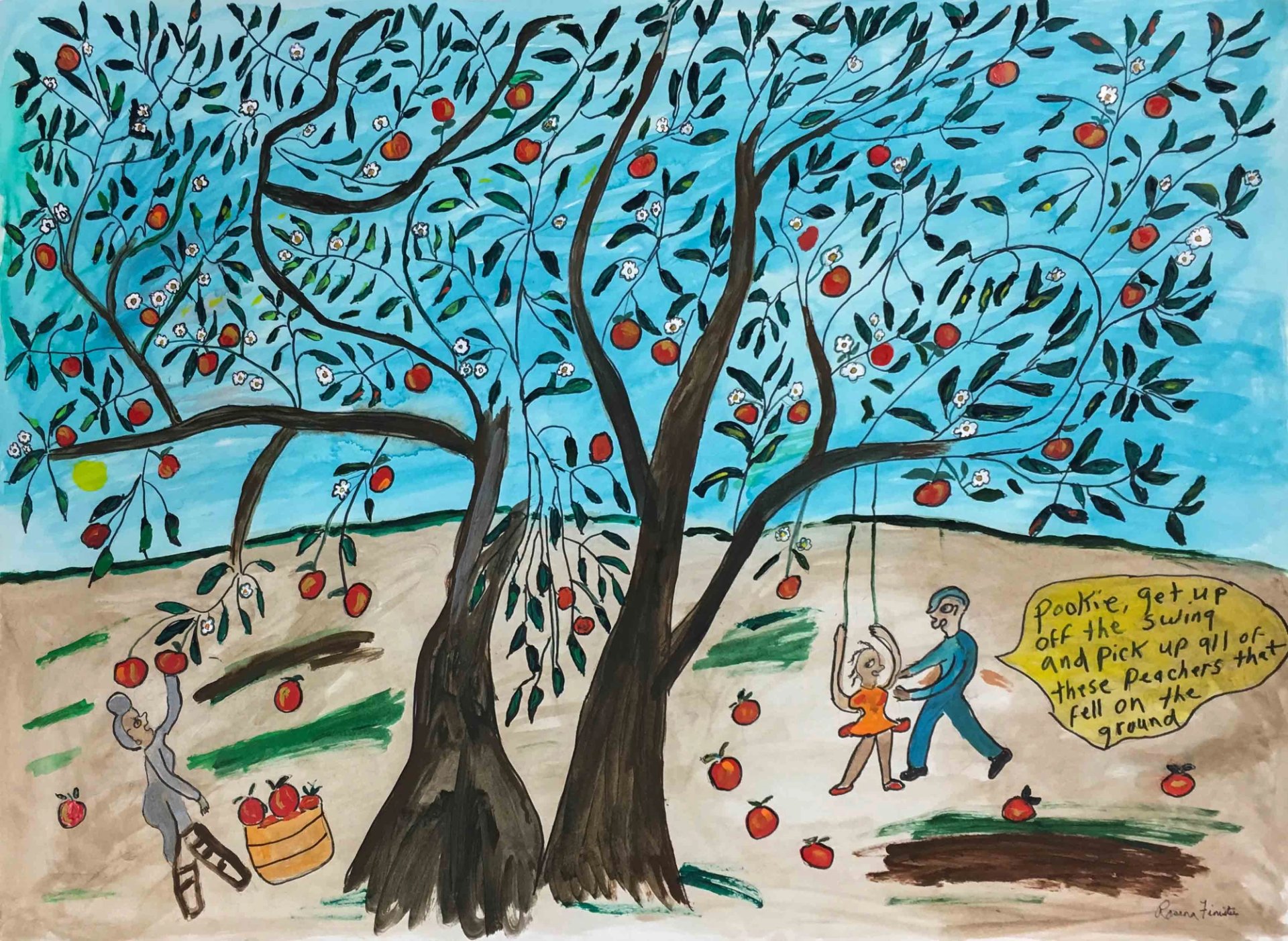

Rosena Finister's Untitled (2019) Courtesy Creative Growth

“It’s gallery-centric but has the communal feeling of an art fair,” Parker said. “Collaboration will be essential going forward. There are so few opportunities in this pandemic-restricted climate. If we can offer small-scale, in-person, gem-like exhibitions in concert with a handful of other like-minded presenters, then maybe we’ve captured what the art world once was…or should be.”

Edlin says the OAF’s original format has clear benefits, one being that it brings a strong sense of community to this niche—but expanding—field, especially among those who have been championing outsider art for decades. “There’s always been a little bit of an underdog status” to outsider art dealers, he says. “Together we’ve all broken through in a huge way over the years.” But, he said, “we pull this off, it begs the question: why not do it again? Not necessarily in lieu of the fair but in addition to it.”