Without Emil Georg Bührle’s success in selling weapons to Nazi Germany, Zurich’s Kunsthaus would not exist in its current form. But as the museum prepares to open a $230m extension that will double its current footprint, the industrialist is casting a long shadow over its plans.

The extension, by the British architect David Chipperfield, was 50% funded by the city and canton of Zurich. It has been designed in part to exhibit Bührle’s collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist art. In 2012, his family foundation agreed a long-term loan of the works—then housed in a private museum outside the city centre—to the Kunsthaus. The plan is to show around 200 pieces by artists including Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh on the second floor of the new building.

City authorities hope the expansion—and the Bührle masterpieces—will boost the museum’s visitor numbers and help to put Zurich on an equal footing with Basel as a destination for art lovers. But Bührle’s legacy is complex and controversial, both because of the source of the wealth that paid for his collection, and because he bought Nazi-looted art.

“The connections between the Kunsthaus and the Bührle foundation go back a long way,” says Erich Keller, one of the historians who contributed to a city-commissioned report on Bührle’s life and career by the University of Zurich, published in November. “There is so much unresolved that might prove problematic in the future.”

The Kunsthaus Zurich extension, by the architect David Chipperfield, has been designed in part to exhibit Bührle’s collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist art Photo: © Noshe

Keller is among the signatories of an online petition, which has gathered more than 2,100 signatures, calling on the mayor to ensure transparency in the museum’s Bührle displays. It warns of “serious omissions” in addressing provenance, demands free access to the collection’s archive, and urges the creation of a documentation centre installed by independent experts to inform visitors about Bührle’s use of slave labour to manufacture weapons, and his purchase of art looted by the Nazis or sold under duress by Jewish collectors.

Born in 1890 in Germany, Bührle served as an army officer in the First World War, then worked for the Magdeburg machine tool factory, in which his father-in-law was a shareholder. He moved to Zurich in 1924 to take over the Oerlikon machine tool factory, where he patented and developed anti-aircraft cannons that were sold around the world.

During the Second World War, his company manufactured weapons for both the Allies and Nazi Germany and he became the richest man in Switzerland. Though the firm featured on an Allied “black list” after the war and arms exports were temporarily banned, it continued to expand internationally.

Looting from French Jews

Bührle purchased several works that were looted from French Jews. In 1948, the Swiss Supreme Court forced him to return 13. He bought nine of them back, including four from the Paris dealer Paul Rosenberg, whose collection had been seized by the Nazis.

In 1952, he donated two large Monet water-lily paintings to the Kunsthaus and also financed an exhibition wing, completed after his death in 1956. In 1960, his widow and children set up a foundation, now known as the Emil Bührle Collection, to oversee a third of the works; two-thirds remain in private hands.

Before unveiling this historically charged collection in the Kunsthaus, the city and canton of Zurich commissioned the university report to which Keller contributed, examining Bührle’s career and the origins of the fortune he used to build his collection.

But provenance research into individual works remains in the hands of the Emil Bührle Collection, which engaged the American scholar Laurie A. Stein. It has published provenance details online and aims to produce a full catalogue of all 633 works that Bührle purchased during his lifetime, in time for the opening of the Kunsthaus extension in October, says the foundation’s director, Lukas Gloor.

Not everyone is convinced of the quality of this work. In a recent article for Zurich newspaper Die Wochenzeitung, Keller accused the foundation of whitewashing the provenance of Cézanne’s painting Paysage (around 1879). Among Keller’s objections to the provenance description on the foundation’s website is the failure to note that the pre-war owners, Berthold and Martha Nothmann, were forced to flee Germany as Jews in 1939. (The website says only that they “left Germany” that year.)

Paul Cezanne's Paysage (around 1879) Emil Bührle Collection

“This provenance research needs to be done afresh, independently and with international involvement,” says Keller, who is publishing a book in Switzerland with a title that translates as The Contaminated Museum: the Kunsthaus Zurich and Future Remembrance. “This can’t serve as a basis for the exhibition in the Kunsthaus. Everything we learn from this research has to be treated with care.”

Gloor’s response is that the online provenance reports aim to list changes of ownership succinctly and are not suited to giving full context. He says he is open to adding new information that emerges. “This work is never completed,” he says.

This provenance research needs to be done afresh and independentlyErich Keller, historian

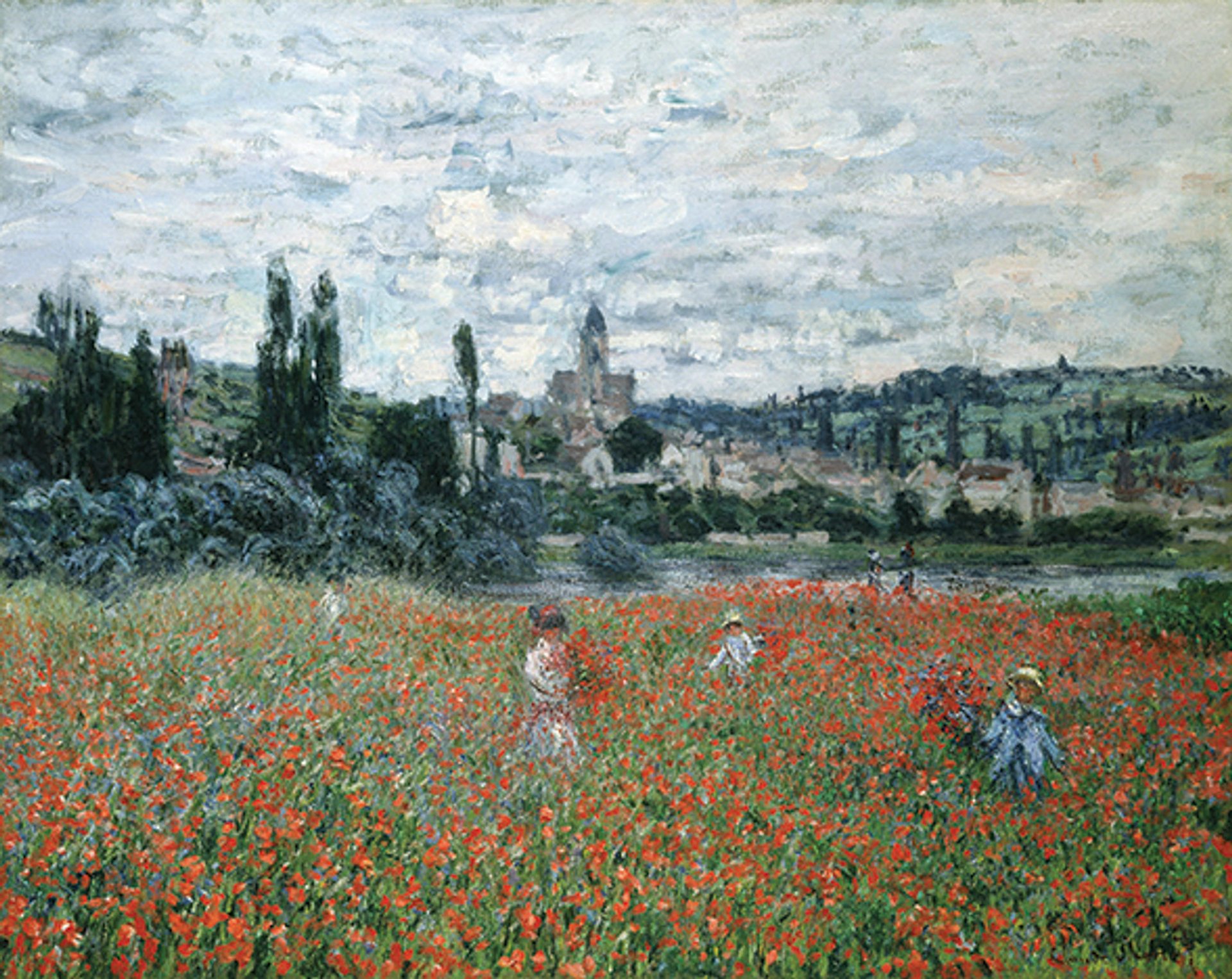

According to Gloor, the foundation faces no “substantive” outstanding restitution claims. But Juan Carlos Emden would beg to differ. He has been trying for almost a decade to recover Monet’s Poppy Field Near Vétheuil (around 1879), which once belonged to his grandfather, Max Emden, a Jewish department-store owner who lost much of his wealth as a result of Nazi persecution. A report by the historian Thomas Buomberger, commissioned by the Emden heirs in 2012, found that Bührle purchased the painting in 1941 for less than half its market value. Buomberger said this was a “loss due to Nazi persecution” and the painting should therefore be subject to restitution. The Bührle Collection has so far rejected Emden’s claim.

Bührle’s family foundation has rejected a restitution claim on Monet’s Poppy Field Near Vétheuil (around 1879) Emil Bührle Collection

Christoph Becker, the director of the Kunsthaus Zurich, says he welcomes the public debate about Bührle sparked by the museum’s extension. In an interview with the Neue Zürcher Zeitung newspaper in December, he promised that the museum will be transparent and objective in its presentation. The Kunsthaus will take responsibility for provenance research with the opening of the new displays this year, Gloor says.

Gloor argues that many of the demands of the historians’ petition will be met: the Bührle Collection plans to grant open access to its archives, and the Kunsthaus extension will have a room serving as a documentation centre on Bührle’s career and his art-collecting activities.

“None of this has surprised us at all,” Gloor says of the open letter to the mayor. Many of the issues it raises were published in a 2015 book, Schwarzbuch Bührle (Bührle Black Book), written by Buomberger and Guido Magnaguagno, who are lead signatories of the petition. “It is the same discussion all over [again], and these discussions will continue,” Gloor says.

At publication time, a spokesman for the Zurich mayor, Corine Mauch, said that she will respond to the petition when it is formally submitted on 27 January. “But it is clear, and the city president has stressed this repeatedly over years, that the presentation of the Bührle Collection works in the Kunsthaus extension will be accompanied by context explaining the history of its origins,” the spokesman says. “Visitors to the Kunsthaus should be informed in an appropriate, contemporary and transparent way about the historical connections. The city has communicated its expectations on this to the Kunsthaus.”