Zanele Muholi’s black-and-white portraits are as beautiful as they are harrowing. Take Basizeni XI, Cassilhaus Chapel Hill, North Carolina (2016), which shows the South African photographer, who uses the gender-neutral pronouns they/them, draped in deflated bicycle tyres, with pursed lips and a far-off look. Muholi’s self-portrait is both personal—the photographer was motivated to stage it shortly after the death of their sister—and political: the tyres reference the history of necklacing, a brutal form of punishment inflicted upon those suspected of aiding the apartheid regime. By upping the contrast in the image, Muholi exaggerates the blackness of their skin tone, reclaiming an attribute regularly defined by others.

“This is important work that needs to be seen. It’s the kind of work that promotes mutual understanding and respect.”Sarah Allen, curator

This is one of 260 works that will be displayed at Tate Modern’s major retrospective of Muholi. The show will cover the artist’s career to date, from Only Half the Picture (2003-06)—an intimate yet intense body of work that tells the stories of individuals from the black queer community in South Africa—to Somnyama Ngonyama (“hail the dark lioness” in Zulu), an ongoing series of performative self-portraits that use symbolic poses and props to address issues of race and representation.

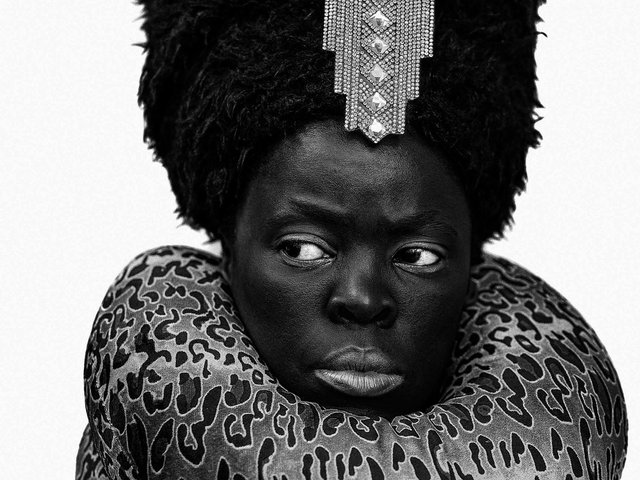

Miss D’vine II (2007), one of Muholi's works that explores the experiences of being LGBTQI+ in post-apartheid South Africa © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson and Yancey Richardson

“This is important work that needs to be seen,” says Sarah Allen, who is curating the exhibition together with Yasufumi Nakamori and Kerryn Greenberg. “It’s the kind of work that promotes mutual understanding and respect.”

Muholi was born in Durban in 1972 at the height of apartheid in South Africa. The country’s 1996 constitution might have banned discrimination based on sexual orientation, but the LGBTQI+ community continues to be targeted, often violently. In the early 2000s, Muholi began to raise awareness of the hypocrisies and hate crimes that remain shockingly prevalent. The subject matter can be hard to handle but, as Allen says, it’s important that the takeaway is not just pain and victimhood.

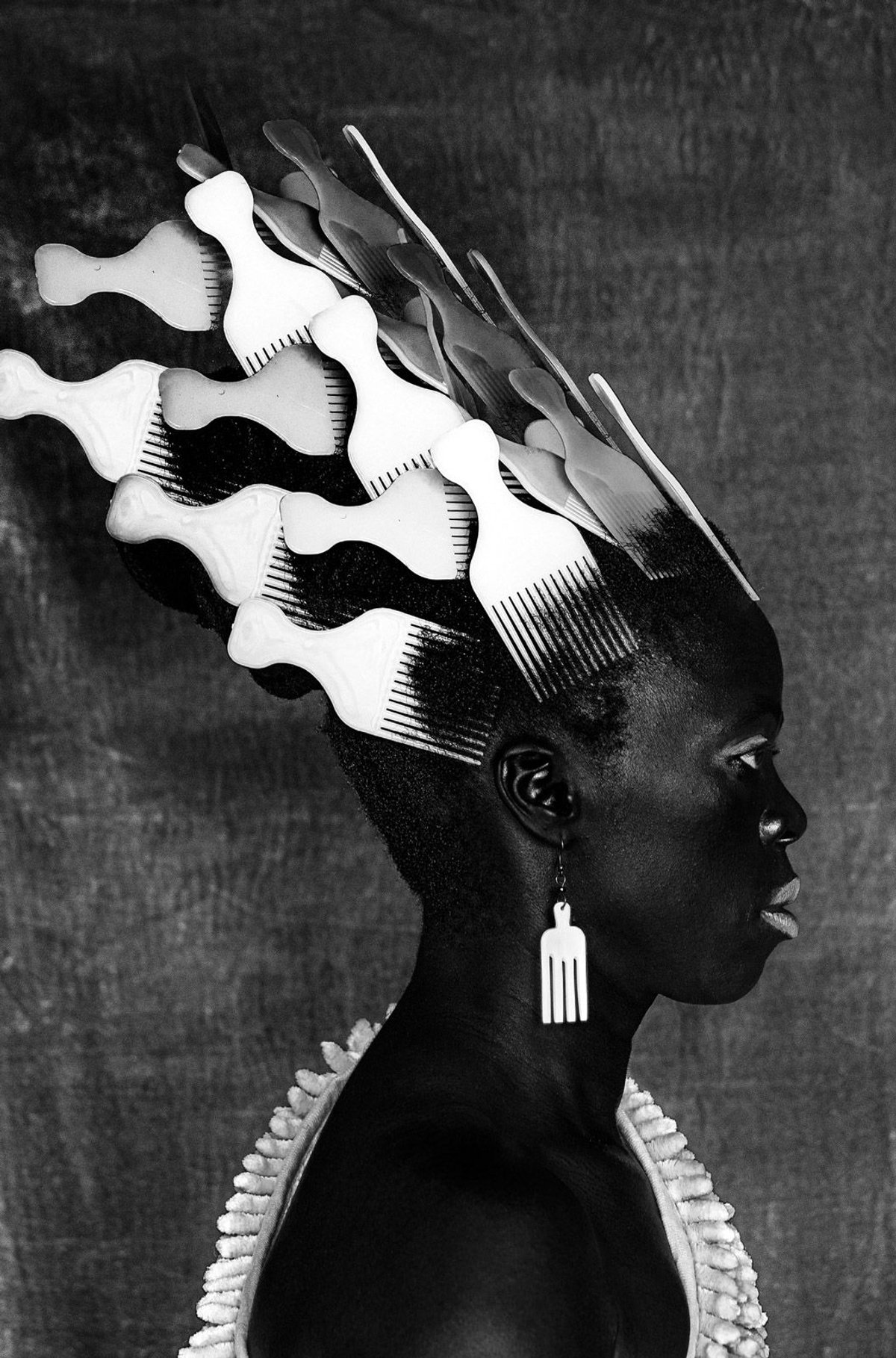

Muholi's Julie I, Parktown, Johannesburg (2016) © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson and Yancey Richardson

“Muholi is keen to emphasise that these people are beautiful, brave individuals who have lives and loves and aspirations just like everyone else,” Allen says. The multifaceted nature of the community is as important as the very real atrocities it experiences.

Muholi trained at the renowned photographer David Goldblatt’s Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, which shines through in the formal framing of the three-quarter-view portraits. In 2002, Muholi co-founded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, which campaigns for the rights of black lesbians in South Africa, and in 2009 established Inkanyiso, a platform for queer and visual media. Activism is at the heart of all that Muholi does and the photographer identifies as a visual activist rather than an artist.

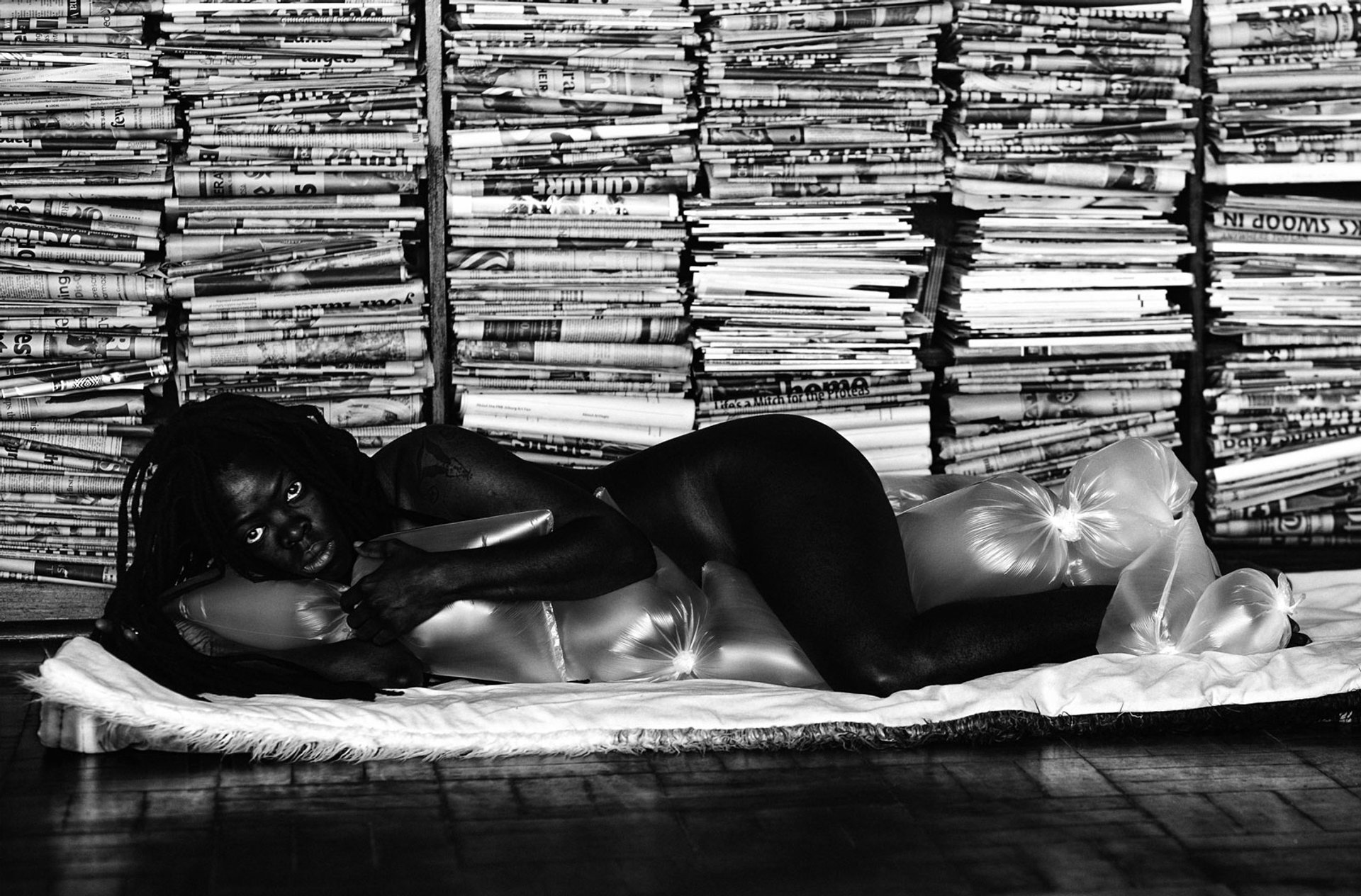

Zanele Muholi's Busi Sigasa, Braamfontein, Johannesburg (2006) © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson and Yancey Richardson

Muholi insists that each of their portraits is about the sitter from the start, either by naming them or featuring a written or filmed testimony alongside. The first portrait in Faces and Phases—another ongoing series, this one depicting black lesbian, transgender and non-conforming South Africans gazing directly at the camera—shows fellow activist and poet Busi Sigasa, who died when she was just 25. Hanging next to it at Tate Modern will be one of her poems.

Muholi’s portraits are powerful political statements, whether related to apartheid South Africa, contemporary media reports, personal experience or all of the above. The visual activist started taking pictures during a dark period in their life; today, the word Muholi most often uses to describe photography is “healing”. With a camera, they were able not only to visualise their own experience but also to comprehend what was happening in the black queer community across South Africa—and, most importantly, to give it a new visual identity.

“We’re trying to ensure that Tate is a platform for these people to speak for themselves and tell their stories,” Allen says.

• Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern, London, 5 November-7 March 2021