There’s something inherently honest about a building or monument. In a fast-paced digital world full of fake news and self-appointed experts, the tangible simplicity of stone, metal, wood and clay cannot lie. If you can see or touch it, it must be true. Consequently, the structures of our past are reliable benchmarks of truth in history…

Not true, of course, as the current debate about whether to topple statues celebrating flawed figures perfectly demonstrates.

Fake heritage is all around us. Buildings and monuments of every era since humans first constructed shelter from the rain, heat or cold reflect the ambition of their builders and are as prone to deceit and bias as anything written or posted on the internet today. Indeed, the truth behind the material remains of our past is made more complicated by both the passage of time and the piecemeal nature of the evidence, both of which guarantee a story only half told.

Architectural and archaeological heritage fakery comes in countless guises, and there are many motivations: the craving for fame or fortune, the desire to fit in or stand out, and the need to reinforce or impose beliefs, or perhaps to project aspiration through architecture.

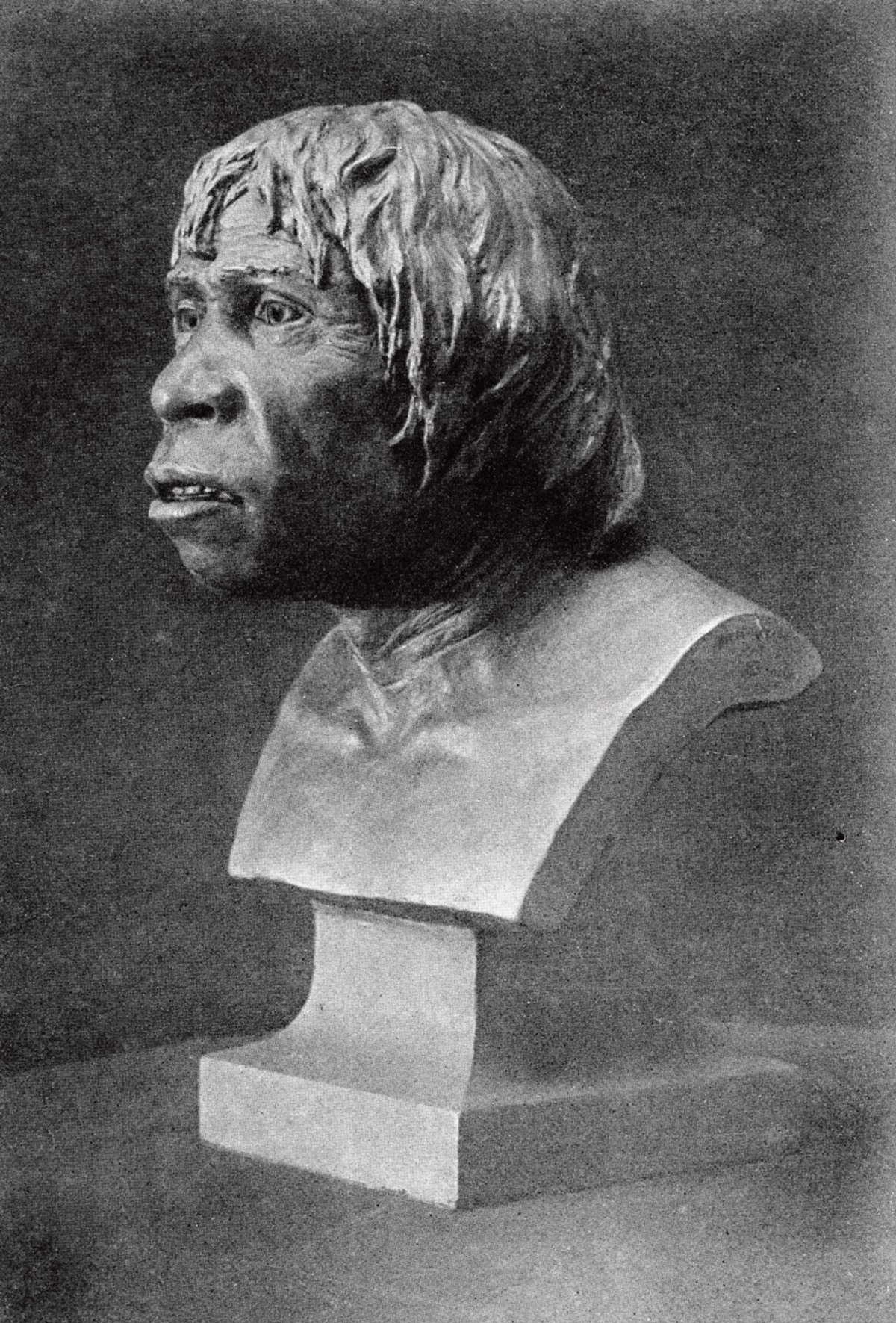

Sometimes, reconstructed heritage is an out-and-out lie. The famous case of Piltdown Man, “the earliest Englishman” and said to be 500,000 years old when uncovered in the early 20th century, turned out to be a jabberwocky of animal parts. Charles Dawson, Piltdown’s “discoverer”, craved academic and social recognition, an addiction that subsequently led to a backlog of dubious discoveries.

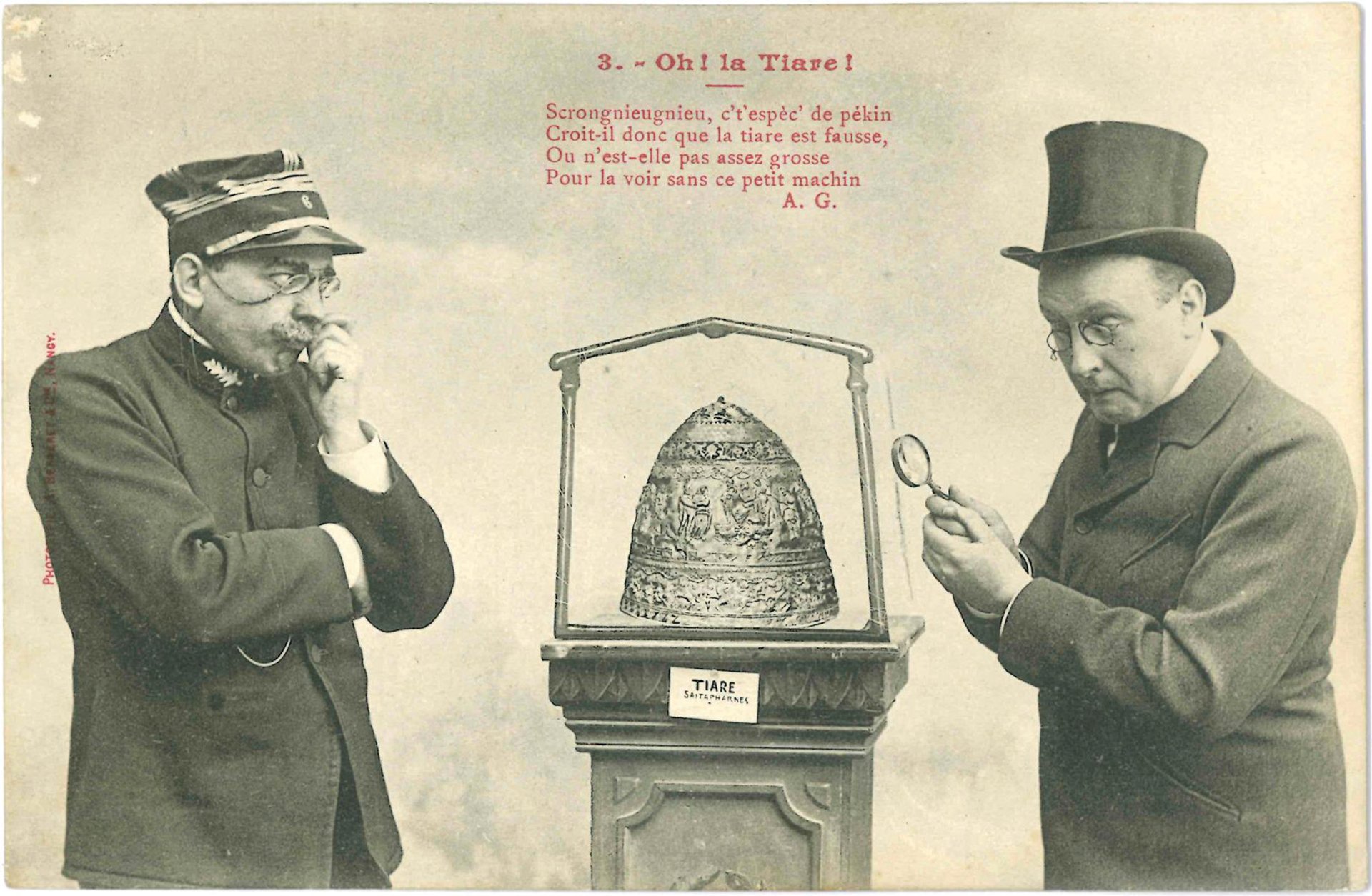

A magnificent golden crown belonging to the Scythian king Saitaphernes, dating to the time of Homer, was sold to the Louvre in Paris in 1896. Suspicions soon surfaced; the decoration depicting scenes from The Iliad was full of detail that was impossible to know at the suggested time of its creation, and while the crown was scratched and pitted, as might be expected after 4,000 years of wear and tear, no weathering touched the panels of elaborate repoussé decoration.

The story soon unravelled, with the trail leading to two Russian art dealers who commissioned the item from a talented local goldsmith and then sold it for the equivalent of €2m.

A satirical postcard of the counterfeit Saitaphernes crown, bought by the Louvre in the 19th century © Wellcome Collection

Money and other motivations

Fame or money may be a significant motivator, but it is by no means the only reason to falsify the past. Sanderson Miller, a gentleman architect, built his reputation during the 18th century by constructing mock pre-ruined castles. These follies were not only eyecatchers in the parkland landscape of his wealthy clients, but also faux effigies reinforcing their family lineage or offering commentary on their politics. What better way to claim overlordship than by pointing to the castle of your ancestors?

Fake heritage can be about what is omitted and ignored—either the subtle bending of history to favour a particular narrative or, more dangerous still, the attempt to redact a culture that does not align with the propaganda of a dictatorial state view. The razing of both mosques and churches during the Balkan conflict, or Mao’s campaign against pre-revolutionary culture in China resulting in the destruction of the Four Olds (customs, culture, habits, ideas), are just two examples of this phenomenon.

But reconstructed heritage can be a force for the good too. The rebuilding of historic city centres, such as Ypres, Warsaw and Frkfurt, marked a restoration of cultural pride and rebirth after the destruction of war. Duplicated heritage may be created to save the real thing from irrevocable damage. The prehistoric caves of Lascaux and Chauvet in France are now almost impossible for anyone to access save for a few experts; consequently, facsimiles of the caves and the extraordinary wall paintings within present the only way in which the public can appreciate the work of some of the world’s earliest artists. A plaster version of Trajan’s column, split into two, joins countless other architectural copies in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Cast Courts, while a full replica of the Parthenon can be found in “the Athens of the South”, Nashville in Tennessee—both examples of reconstructed heritage serving an educational purpose.

The Gothic Tower, designed to look like a picturesque medieval ruin and based on a 1749 sketch by the architect Sanderson Miller for his patron, Lord Hardwicke, the owner of Wimpole cmglee

Why should we care?

The fabric of the past is important: for understanding where we have come from; for the lessons it offers for the future, good and bad; for the distinctive character it gives to our cities, villages and countryside; and for its contribution to identity, society, economy and politics.

As we have seen, history is rarely a neat, consensual narrative—a single, agreed sequence of events—but an array of alternative interpretations and views coloured by vastly differing perspectives. Within the context of such in-built ambiguity, the presence of fake heritage and the increasing opportunities for it to flourish in a technology-rich world are considerable. To the perpetrator, the spoils, be they justification, inspiration, glory or riches. When confronted by this compendium of falsehood and reproduction, the task is to look closer when it comes to the past, to be curious and consider the ambition and stimulus of those telling their story, to be careful of the roots of nationalism and challenging of those who ignore evidence and scientific fact.

• John Darlington is the executive director of World Monuments Fund Britain. His book Fake Heritage: Why We Rebuild Monuments will be published by Yale University Press on 13 October