A site-specific land art exhibition staged in a forest outside Moscow has struck a nerve in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic and political crackdown. Cha Shcha, a play on the Russian word for “thicket”, opened on the grounds of Pirogovo, a resort and housing complex in a forested area outside the Russian capital on 20 September (until 20 October). It is drawing rave reviews from the city’s usually cynical art community, which is still reeling from lockdown.

Nearly 30 artists ranging from Soviet-era giants such as Francisco Infante-Arana and Nonna Goryunova, to contemporary artists such as Pavel Pepperstein, and Pavel Otdelnov, created installations that are scattered throughout the woods. The exhibition also resulted in a new art group called Artistic Solitude. A YouTube video with dramatic drone footage offers a tour of the site and works.

Alexander Korytov, the director of Jart Gallery, who organised the exhibition, said it was conceived before the lockdown, but planned during the time of strictest anti-coronavirus measures. Self-isolation and the forest played into the “idea of asceticism” that is reflected in works such as Valery Koshlyakov’s cave-like Ikonos, which draws on the reverse perspective and “mythical architecture” of Russian icons and the avant-garde.

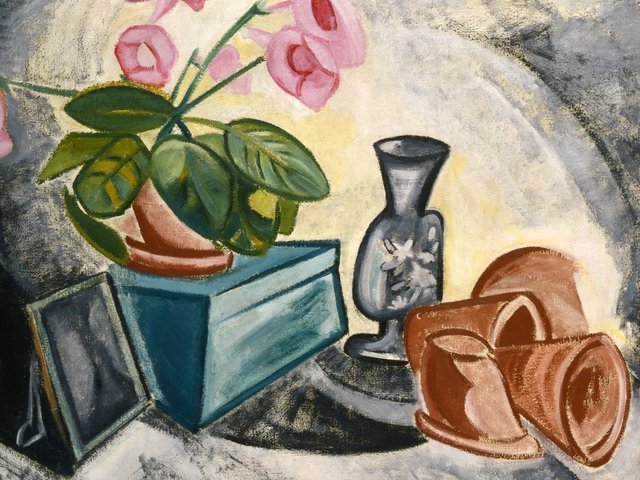

Koshlyakov guided the construction of Ikonos via Zoom, as he was in France at the time. The builders had experience working with museums and some are artists as well. Pepperstein’s project includes a watercolour that serves as the exhibition’s logo and an installation called Furniture in the Forest, which consists of a library of bookcases in the midst of a thicket, with an armchair for reading under a 3m-tall mushroom.

Valery Koshlyakov's Ikonos © Jart Gallery

Earlier this month a preview of Cha Shcha, showing sketches and models of the installations, won “best stand” at the Cosmoscow International Contemporary Art Fair. The connection with the forest at Pirogovo sets off “deep processes of ties with nature,” Korytov says, and helps people “perceive art with an absolutely pure consciousness”.

Korytov adds that the Cha Shcha artists are also pleased with the results. “All of these circumstances of heightened uncertainty have a big impact on what is happening now, so we are also very happy that we could inspire such a big creative team.”

The exhibition’s curator Andrei Erofeev likened the forest refuge to a revival of the “internal emigration” of artists and intellectuals in the Soviet era and a desire to seek protection from “approaching totalitarianism”.

“More and more people, entire social groups, are withdrawing from close social interaction, especially from interaction with the authorities,” Erofeev says. “They are completely disenchanted with the authorities, refuse to cooperate with them, and are searching for a variant of autonomous life. This is a form of soft protest, of soft resistance, about which Ernst Jünger, the German soldier and philosopher also wrote.”

The director of Moscow’s Pop Off Art gallery, Sergey Popov, wrote in a Facebook post that the exhibition harkens back to the happier times of the early 2000s and the Art-Klyazma contemporary art festivals that were organised on the same site by the contemporary artist Vladimir Dubossarsky. The “seemingly careless and full-of-prospects atmosphere of those years” is long gone, Dubossarsky says. “[But] the exhibition that Erofeev has fashioned is smart, precise, dark and in the larger scheme of things, angry.”