During the last Great Depression, the number of dance marathons skyrocketed. In lieu of other work, desperate participants would twist and twirl for upwards of 30 hours, watched by a frenzied audience. Cash prizes aside, a dancer would also be fed and sheltered for the duration of the competition until finally collapsing to the rapturous applause of the crowd. In MANIAC at Klemm’s (until 24 October), the French artist Émilie Pitoiset considers our daily, never-ending performances in the era of surveillance capitalism. Metal rod figures are placed around the gallery space, each choreographed mid-movement in “a dance”—as Pitoiset terms it—“of collapse and exhaustion... until the body disappears”. Draped over each faceless structure are clothes created by the artist—a dress fashioned from a looped seatbelt; jackets sown with security tags and spikes reminiscent of hostile architecture. Wrapped around the walls she has imprinted imposing CAPTCHA signs, which typically accompany a computer-generated demand to prove one's own humanity.

This is Foucault's panopticon model for the Instagram age, where the digital state's watchful eye has created an arena in which we must vie for the monetised attention of the crowd. Imagining modern life as a dance battle to the death, the show questions how each movement of our body can be understood through a constant, algorithm-dictated demand to perform. Today, dance marathons no longer hold sway. Instead, we dance to Doja Cat on TikTok. Crowded halls of hundreds have become virtual audiences of millions. MANIAC asks us to contemplate not only this brutal competition, but who we become in the process of participating. In one corner, two figures cling to one another, seemingly holding each other up from falling down. Humanity, Pitoiset seems to suggest, is best evidenced within gestures of vulnerability. It is our ability to ask for support, and offer it to those who need it most, that tells you who we really are.

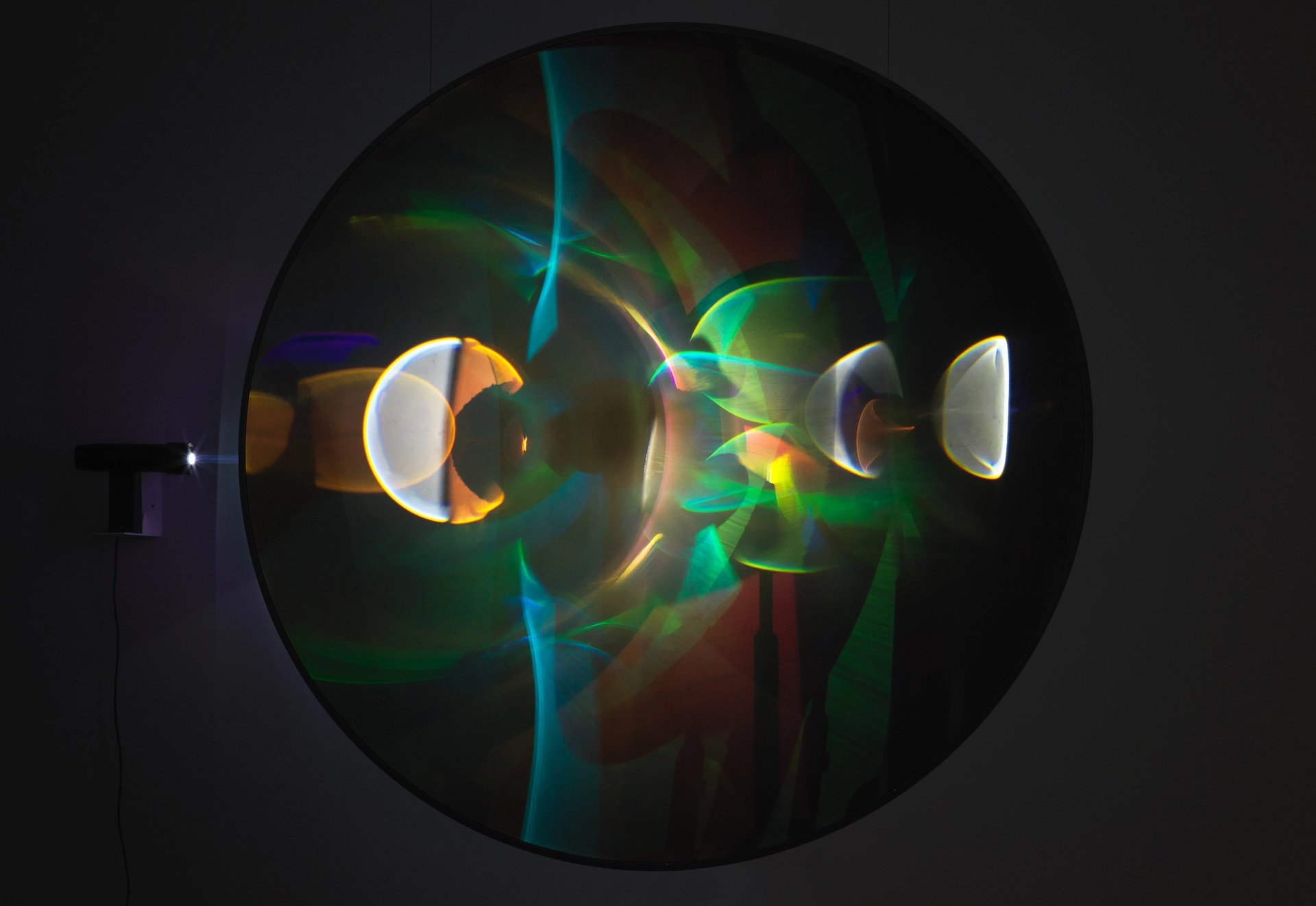

Olafur Eliasson's Interpretive flare display of unthought thoughts (2020) © Studio Olafur Eliasson courtesy the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Few artists today make work as optically pleasing as Olafur Eliasson. Near future living light at neugerriemschneider (until 24 October) continues several threads of the megawatt Icelandic artist's practice, including experimentation in sensory perception and our relationship with the natural world. Most captivating is a new series of kaleidoscopic installations presented in a darkened room, which shine light onto angled mirrors and motor-driven lenses to project gently shifting coloured elliptical patterns onto the walls. If these works are read as rudimentary constructions of the human eye, then Eliasson asserts that what we are drawn to—the mesmeric, multi-coloured projection— is not visual phenomena itself, but our mind's wondrous perception of it. In a second room, plates of coloured sea glass are layered atop each other on a driftwood shelf—merging planes of pure colour together to create shades anew. Presented with overlapping realities, reliant on mere positioning, Eliasson makes clear the contingent nature of the visual world and the marvellous nature of our imaginative capacity.

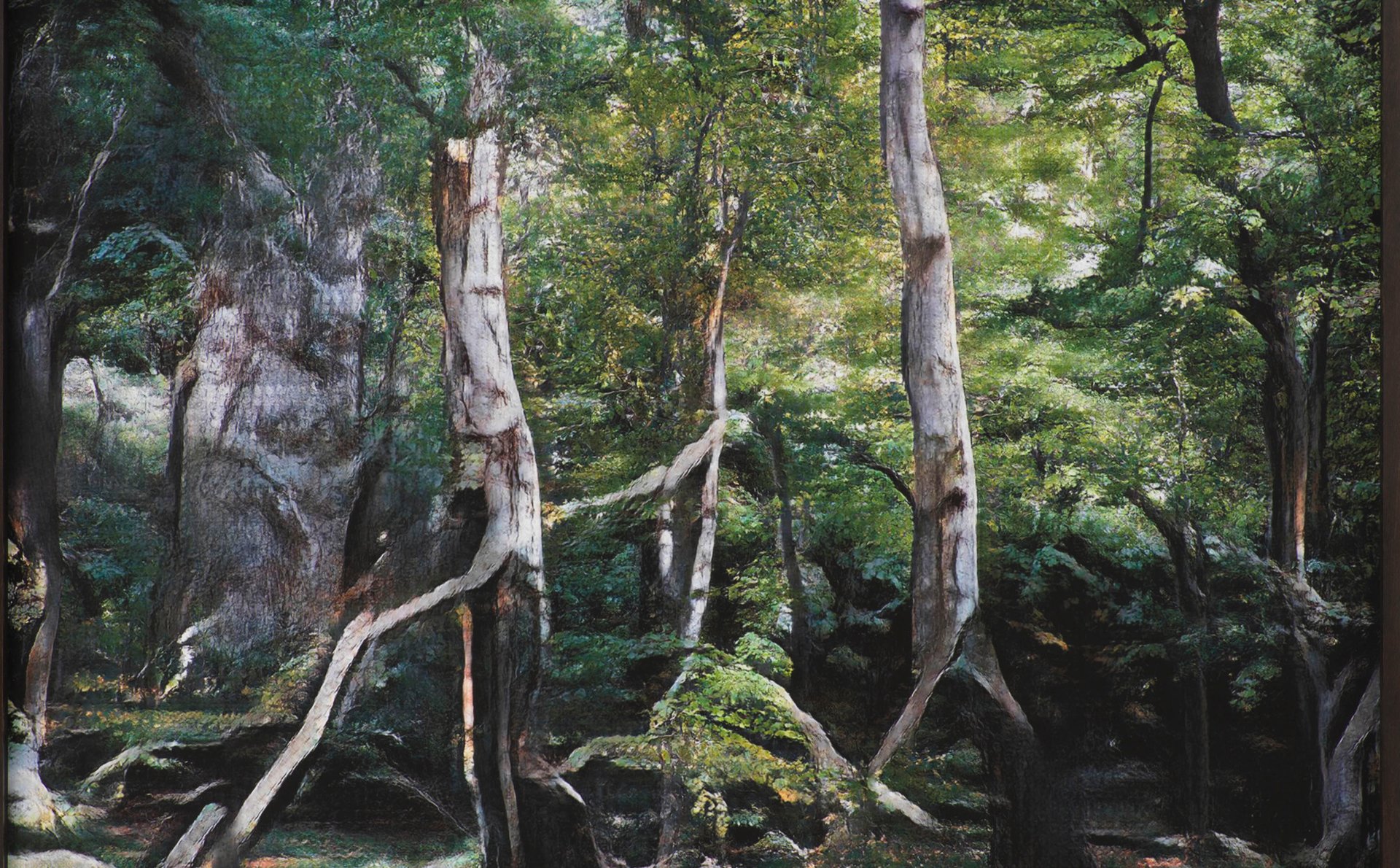

Andreas Greiner's Jungle Memory (2020) © Andreas Greiner, Images courtesy DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, Berlin

Andreas Greiner's Jungle Memory (until 1 November) fills Dittricht and Schlechtriem's basement gallery with an ersatz forest. Videos of artificial intelligence-generated images based on photographs of an endangered woodland in Lower Saxony accompany vertical pillars of real spruce. These bare, emaciated former trees have had their bark scraped off and heaped at their bases; wooden scaffolding merges into their forms. Offering a fake, digital vision of a forest, reminiscent of Romantic landscape paintings which depict nature as the great unknown to be conquered, alongside the starker reality of our exploits, Greiner emphasises the thorny, detrimental relationship between human creativity and ecology. Alongside the show, Greiner has also launched an initiative to plant a diverse forest in Lower Saxony, with a corresponding series of educational programs for the surrounding communities.