The Tate announced earlier this month that it would reopen its galleries on 27 July, after more than four months’ closure. But while most of its shows have been extended or postponed to a later date, Tate Modern’s survey of the British film-maker Steve McQueen’s work will not reopen with the collection displays and the exhibitions by Andy Warhol and Kara Walker on Monday. Social distancing rules have cut short McQueen’s show, so instead of running for three months as originally intended, it was open for just five weeks.

McQueen declined to comment but Thomas Dane, who represents him, says he and everyone connected to the project are “hugely disappointed”. He adds: “Steve had waited a long time for this show; this was his homecoming, in a sense.” Achim Borchardt-Hume, Tate Modern’s director of exhibitions and programmes, says that the gallery was “very hopeful that we could reopen the exhibition” as the lockdown began. But “it was only as the social distancing guidelines became more and more detailed” that doubts began. “As we were working through every detail, it was becoming impossible to conform to the social-distancing guidelines within spaces with limited visibility.”

When it opened in March, McQueen’s show was lauded for its elegant, spacious layout. “The strength of the exhibition was that it was such a beautifully designed environment,” Borchardt-Hume says. “It was so much Steve's brainchild, the layout and the way that the visit was choreographed.” But several spaces were problematic: five rooms with single films or photo and sound works had only one exit and the film Western Deep also had a cinema-style seating structure. “If it’s possible to use two separate doorways and if there's enough breathing space, given that the number of visitors anyhow will have to be restricted, then that is not so difficult to accommodate,” Borchardt-Hume explains. “It is more difficult to accommodate when it is a formal cinema situation. Because then you have the challenges of being in steady position over a prolonged period of time.” Ultimately, he says, “you have to make the safety of visitors and of our own staff the priority”.

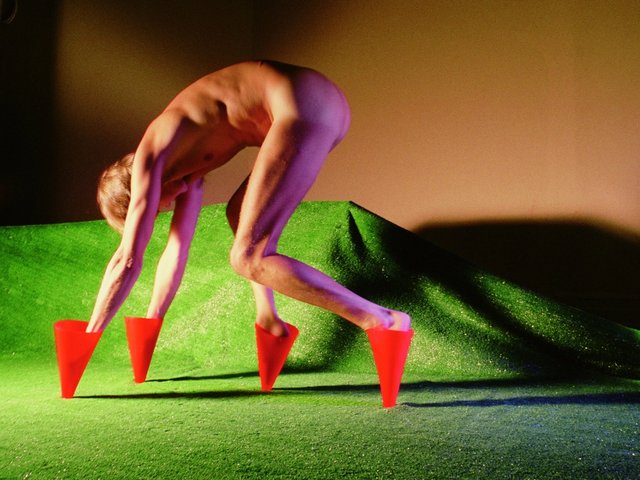

Steve McQueen, Static (2009, video still) © Steve McQueen. Courtesy of the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery

There are implications for the display of any video art—whose acquisition has greatly increased in museums like the Tate in recent years—during the pandemic. Several video works in Tate Modern’s collection hang will remain inaccessible. “The entire walk through the collection will have to be a one-way street, just as in shops, just as anywhere else,” Borchardt-Hume says, “so as long as you can enter and exit the room via separate doorways, that makes it a lot easier”. Igor Grubic’s East Side Story (2006–08), with a separate entrance and exit, will be on view, “but some of the ones that are in the more enclosed rooms, at the moment, they have to be off limits”, he admits.

If, as many scientists predict, the coronavirus continues well into next year, and perhaps beyond, it seems likely that the display of video in the orthodox, enclosed “black box” space may be impossible for some time. Cass Fino-Radin, the founder of Small Data Industries, which conserves media and digital art and advises on its display and storage, and a former conservator of time-based media at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, says: “Now is obviously an opportunity for artists, collectors, institutions to be experimenting with new ways of showing work. And I'm seeing a fair amount of that happening.” But, they say, “in cultural heritage, broadly speaking, there's always a bit of being behind the curve, not so much in terms of the technologies, but the fluency with the technologies and knowing what is even possible in the first place.”

Fino-Radin suggests there are models for the socially distanced presentation of video, like 2012’s MoMA Media Lounge, which offered booths that individuals or small groups of visitors could enter and explore the museum’s collection, on what it described as “historically accurate display technology”. Fino-Radin says: “For video-art nerds, it was like a dream.” But it was “kind of off the beaten path, it didn't really have the kind of institutional support it deserved”, they say. They also cite the innovative displays involving sound-proofed clear screens devised by the multimedia artist Ed Atkins at the video art collector Julia Stoschek’s gallery in Düsseldorf in 2017 as another example.

Steve McQueen's survey will be adapted for the vast industrial spaces of the Hangar Bicocca in Milan, which hosted Anselm's Kiefer's Seven Heavenly Palaces in 2018

As Thomas Dane says, McQueen is “so particular about the way his work is shown and isolated, etc—he does have very high installation requirements”, and Fino-Radin suggests that artists used to “designing these really prescriptive installations” may need to become more flexible in the post-pandemic era. “It'll probably take a few years for us to see that, but I think it's inevitable,” they say. “I mean, I think this is changing everything.” In any case, they say, artists “who have a fair amount of market experience”, and sell works to private collectors, do not necessarily expect the same perfectly controlled conditions for their work outside the museum and so “are used to making those kind of like trade-offs or compromises, or just having that flexibility”.

And flexibility is the order of the day for the McQueen exhibition’s next venue, Hangar Bicocca in Milan, which will now open in April 2021. In a statement, the venue’s artistic director, former Tate Modern director Vicente Todolí, says that the exhibition in Milan “will be completely readapted to the vast ex-industrial spaces” and will feature a new work, given its premiere in Milan. And while it was too late for McQueen’s exhibition at the Tate, another giant of video will have a massive Tate Modern retrospective later this year. “In October we will open Bruce Nauman,” Borchardt-Hume says, “and that will be an exhibition that is very heavy on moving-image installations. But because we are planning it now, we can plan it so that you can negotiate those rooms clearly and safely.”

Curators are determined that film and video remain vital media in museums, even if the enclosed “black box” may, at least for now, have had its day.