Why delve into the 1960s art world again? Is there anything left to say about the post-war period in London and the main protagonists on the capital’s art scene? Our Book Club book of the month for July, London’s New Scene: Art and Culture in the 1960s, hones in on the decade when everything seemed to swing. We recently spoke to its author, Lisa Tickner, in an interview streamed live on Instagram.

She discussed how the book emerged out of other projects such as conference papers and academic articles. “I wanted to know why [the Italian film-maker] Michelango Antonioni, who was a European auteur, would come to London to make [his film Blow Up] in 1965 and 1966? I wanted to know how a commercial gallery was set up and organised, for instance,” she says.

London began to boom for several reasons in the 1960s. “Air travel was very important; there aren’t scheduled passenger jets until around 1959, and these really take off in the 1960s.” But it was an international art world only in the sense that it reflected and encompassed the countries of the western Nato alliance”, she says. Increased media presence in Western countries also changed the art landscape.

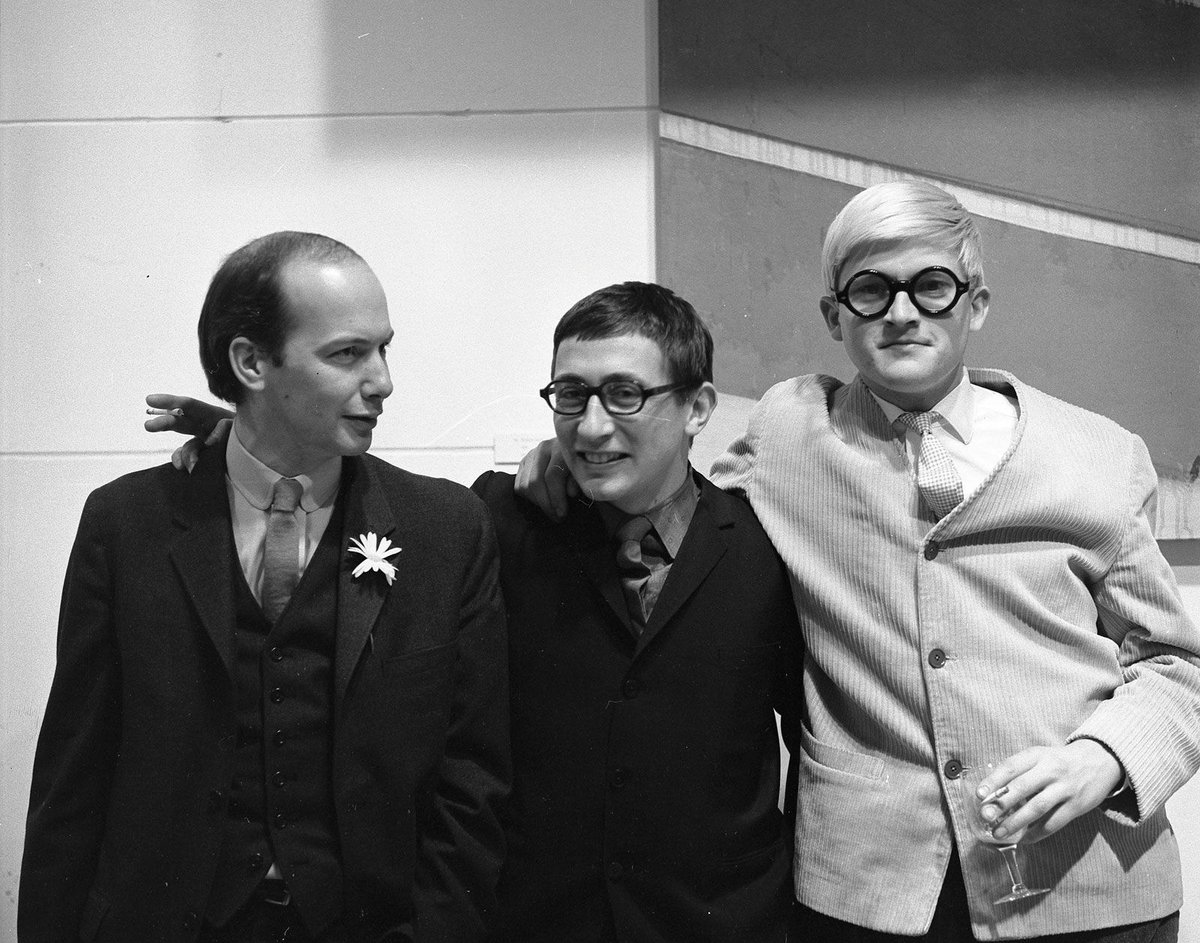

Lisa Tickner

The question of whether the art world was becoming less elitist in the post-war period is complex, Tickner says. Buying art meant purchasing one-off pieces, she says, so in that sense it was a privileged pastime. On the other hand, “galleries were free to go to. We didn’t have the landscape of public galleries that we have now… if you were interested in contemporary art, British or international, you would go to the commercial galleries like [John] Kasmin or Robert Fraser, or to the Whitechapel or the ICA, and they were free.” It was arguably less elitist than now when students have to pay tuition fees of more than £9,000 annually, she adds.

The book’s journey began around 15 years ago when Tickner started researching the Kasmin Gallery, the focus of chapter two. John Kasmin founded his space in 1963 on Bond Street, where he showed works by Larry Poons, Kenneth Noland and Anthony Caro, among others. “[Kasmin] had such unrivalled resources, he carried out an enormous number of interviews that can be listened to in the national sound archive [at the British Library],” Tickner says. Kasmin’s business papers are also stored at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.

Tickner says she focused on “networks”, looking at the “conduits through which power, money and ideas flowed, networks in that broader sense”. Crucially, the book is not strictly a survey but a sequence of seven case studies, moving from 1962 to 1968; the first part focuses on Ken Russell’s “documentary” Pop Goes the Easel—a jaunty overview of young British pop artists—while the last section looks at the Hornsey College of Art sit-in when students were in revolt.

The protest at Hornsey College mattered for several reasons. “The original Hornsey sit-in was provoked by very difficult circumstances in terms of poor resources, bad accommodation, a sense that a few starry projects were taking the attention of the senior staff. But once the sit-in started—it was intended to last just 24 hours—it actually expanded [into] six weeks of debate which stretched into questions of what art education was and for, and how the world could be improved by artists and designers,” Tickner says.

At the other end of the spectrum, Tickner explores the role of the Stuyvesant tobacco company as a sponsor of the New Generation series of shows at the Whitechapel Gallery spearheaded by Brian Robertson. Tickner also points out that the sponsorship of the pivotal conceptual art show When Attitudes Become Form at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1969 by Philip Morris, another tobacco conglomerate, has been overlooked. “[The exhibition curator] Charles Harrison was told that he could not put on the show he had planned… this show came trailing quite a bit of money in its wake.”

So did the evolving art ecosystem in the capital lay the foundations for today’s commercially-minded art scene? “There were certain developments in the 1960s which, if they didn’t lay the foundations, certainly accelerated certain components of the art world with which we’re familiar today, and one of the most obvious of those is business sponsorship,” Tickner stresses.

For more insights—including why the US pavilion trumps the British entry at the Expo’67 in Montreal and how the photography of Antony Armstrong-Jones, Princess Margaret’s husband, is imbued with a “sense of mischief”—watch the full interview @theartnewspaper.official on Instagram (tilt your head).

• London’s New Scene: Art and Culture of the 1960s, Lisa Tickner, Yale University Press, 416pp, £35 (hb)

• For a review of London's New Scene, see Sex, Soho, cocksure snappers and cigarette money: the making of London’s 1960s art world

• Sign up to The Art Newspaper's Book Club newsletter here