Monuments have taken a beating this past week—traditional monuments, that is, statues of what you might call failed white male conquerors, so prevalent in the lingering Confederate South. Shortly after the current occupant of the White House gave a speech at Mount Rushmore on 3 July, protestors in Baltimore pulled down a Christopher Columbus statue and threw it in the harbour. Meanwhile, in a counter move, a statue of Frederick Douglass was toppled in Rochester, New York, as the abolitionist’s famous “What to the Slave is the 4th of July” speech circulated widely on social media. Suddenly we find ourselves asking the big questions: What does this country stand for, whose country is it, and what is its future?

Monuments, as we tend to think of them—statues in public places, or buildings with namesakes emblasoned across their façades—are, formally speaking, a thing of the past. They hearken, of course, to olden days—the Civil War, the American Revolution, and, further back, to the prototypes of imperial Europe and ancient Rome. Monuments tend to celebrate the order that mankind has imposed on the world, and I think most of us will agree, there are achievements well worth honouring: the values of democracy, the end of slavery, universal suffrage, scientific and medical advancements, or greatness in philosophy and letters. But as we continue to question the success of these ideals, as any free society should, we find ourselves asking: what order has been achieved, and at what cost to whom? Under such conditions, the old monuments start to look not only tired but offensive. Standing there in all their bronzed confidence, they shift in meaning to memorialising not the ideals they were built to represent, but the failure of those ideals instead.

Meanwhile, a lasting monument to this time accumulates in forms we do not normally associate with monuments. The photographs circulating widely, visualising unrest in various places across the nation, and sometimes centered around existing monuments, is generating a kind of meta-monument, forwarding new ideals built upon (or formed against) the standing order. The president plays to this intentionally when he stands in front of Mount Rushmore, invoking that monument’s symbolic—albeit kitsch—power and amplifying it through a media blitz of his own image alongside it.

Kara Walker’s A Subtlety (2014)

Certain artists have developed a similar strategy, adopting the forms of the symbols they critique. Kara Walker’s A Subtlety (2014), comes to mind, with its massive, bare-breasted, sugarcoated sphinx-like “mammy” presiding over a field of “sugar babies” in the old Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, New York. Consciously mimicking traditional monuments, A Subtlety not so subtly turned the model inside out. Instead of honouring the achievement of industry, it called attention to the darker, underlying forces of American capitalism—namely, the sugar trade and its dependence on slave labour. And, of course, the entire spectacle was created not only to be visited but also photographed, spreading images and ideas systemically through social media networks in much the same way sugar was distributed during the colonial period. In terms of exposing the veins of systemic racism, few have done it better than Walker.

Clearly, there is a new spatial order in relation to monuments. In the pre-modern world, before elaborate communication systems were in place, monuments sat physically in town squares or other high-traffic areas, where they were seen by anyone passing by. Today, the internet is our town square, with its websites—Google, Yahoo, Facebook, Twitter, and various news outlets—visited by billions across the planet. And the monuments we see there are placed by a constant, recombinant algorithm—part human editor, part machine—based on what is trending: the best news photos of the day, viral videos of fit-throwing anti-maskers, and, of course, the amateur visual documentation taken by bystanders and police security cams that first initiated the waves of protest.

Joe Rosenthal’s 1945 photo of flag-raising soldiers at the Battle of Iwo Jima was translated into a bronze monument outside Arlington, Virginia

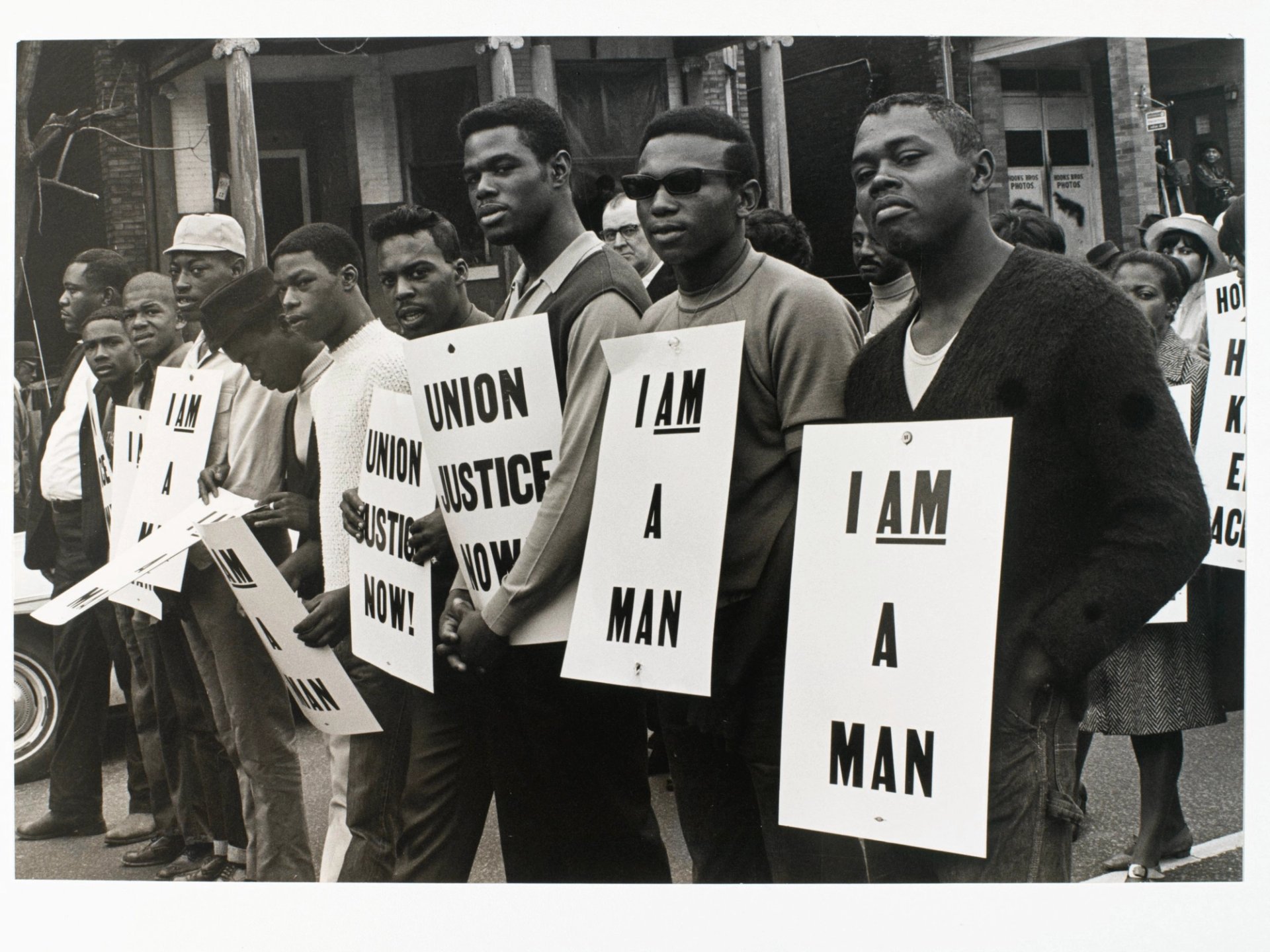

But which of these would-be internet monuments will last? Which will be more than a momentary experience of choreographed outrage or titillation? Which will ascend to a more permanent station in the cultural imagination, such as Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier, a 1936 casualty of the Spanish Civil War; or Joe Rosenthal’s 1945 flag-raising soldiers at the Battle of Iwo Jima, which was translated into an actual bronze monument outside Arlington, Virginia; or Gordon Parks’ American Gothic, of 1942, a portrait of Ella Watson, a Black cleaning woman who worked in Washington, DC; or Builder Levy’s great photographs of the “I Am a Man” march, from Memphis, 1968? The answer to that question is as much about the ideals alive today, and which of those will be valued and remembered by future generations, as what once made a good photograph. As with any bronze memorial, if the ideas do not live in some compelling form, the image dies with it.

Builder Levy, I Am a Man/Union Justice Now, Martin Luther King Memorial March for Union Justice and to End Racism, Memphis, Tennessee (1968)

Perhaps the most gratifying statement of the recent, fraught 4th of July weekend came as a simple visual history lesson by Matthew Buckingham. His 2002 photograph titled The Six Grandfathers, Paha Sapa, in the Year 502,002, is a geologists’ fantasy of how Six Grandfathers, the geologic rock formation in the Black Hills of South Dakota, so named by the Sioux before whites appropriated the land and conceived Mount Rushmore as a “shrine of democracy,” will appear in 500,000 years—the time estimated for the presidential faces to erode at the hands of nature. The story of Mount Rushmore is one of those triumphal tales even schoolchildren have learned to distrust. And the visionaries responsible for the gargantuan, carved façade come with their own political baggage: Doane Robinson, who headed the effort, was part of the 20th-century revival of the Ku Klux Klan.

Despite a 1980 Supreme Court ruling in favor of the Sioux Nation, acknowledging that the Black Hills were illegally appropriated by the US government, and granting $120 million in reparations, the significance of the site remains hotly contested. The Sioux have refused payment and still hold claim to the land. The power of Buckingham’s image, and his writing on the subject, lies partially in the audacity of the original crime—the theft of the land from Native peoples—and the ongoing battles over Mount Rushmore’s cultural ownership. But the real significance lies in the realisation that the fight itself, like most things, means nothing from the longer view of nationhood and time. Monuments, whether etched in stone or affixed as photographs, are but fragile fantasies of permanence.