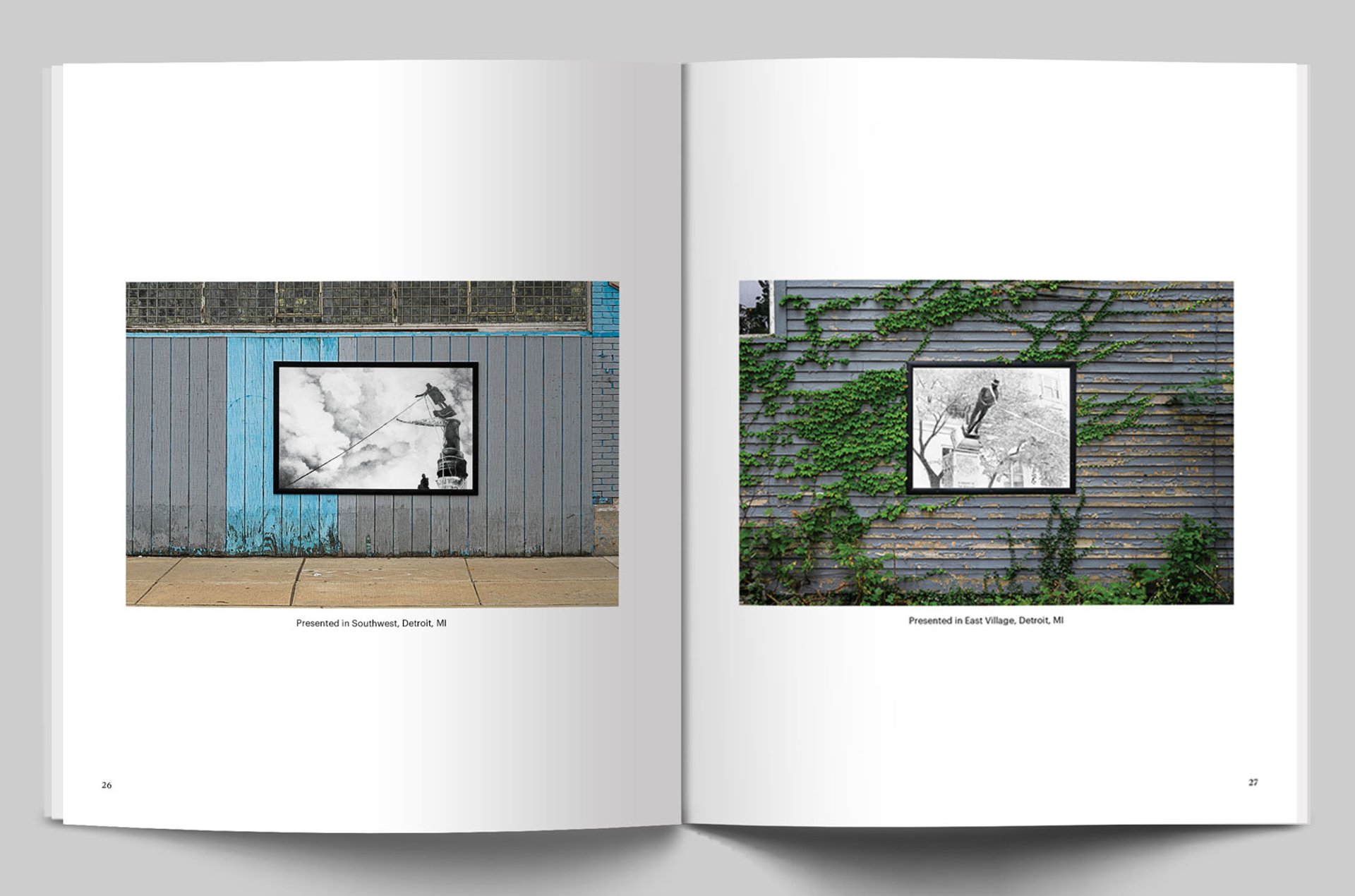

A new catalogue called Iconoclasm, featuring dramatic examples of iconoclastic annihilation across the centuries, could not be more timely in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests worldwide. The large-scale graphite drawings depicting the destruction of statues and monuments are by the Berlin-based, US artist Sam Durant. The drawings in the catalogue were shown at the Library Street Collective space in Detroit late last year and also placed in key locations throughout the city. The catalogue includes shots of the works in situ in Detroit, along with Durant’s images showing the toppling of the Vendôme Column in Paris in 1871 and the removal of colonialist statues in the Caribbean and South America, among other examples.

Sam Durant's drawing Paris 1871 (2018)

The Art Newspaper: How did people in Detroit respond to your provocative public art works?

Sam Durant: We did not know what to expect as these were original drawings mounted in public places. I imagined people would tag them or maybe deface them. The idea was to put the drawings themselves into public space and to be as vulnerable as the statues depicted in the drawings. I tried to have a mix of different types of icons: religious, political and cultural.

In the end nothing was defaced. This could be understood in different ways; either no one cared, or no one noticed, or they noticed and treated them with respect. Unfortunately, I have no way of confirming my assumptions. We did a lot of research with the neighbourhoods that we put the different images in. I hoped the gesture of putting particular drawings into a certain neighbourhood would be taken as a sign of respect.

How has the Iconoclasm project developed?

In 2008, I was invited to participate in an exhibition at the Dutch cultural centre Stroom Den Haag called When We Last Spoke About Monuments. I created a digital database of defaced sculptures and statues. That was the beginning. It was a massive research project, which involved cataloguing what I would categorise as defacement or destruction from below. It was not about the official removals of statues but spontaneous eruptions of violence against symbols by people.

That project was international in scope and is still ongoing. In terms of the Iconoclasm exhibition and book, I wanted to really look at it in a geographically dispersed global way but also as a trans-historical phenomenon, situating it across a span of history. We tend to think of whatever is happening in the moment as something unique, and of course it is, but it is also connected to a long history; when we disagree with a symbol, we want to get rid of it.

A spread from Iconoclasm

What were your reference points?

[The art historian] Dario Gamboni’s book Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution (1997) was very influential for me. Iconoclasm and destruction in art is something that I’ve been interested in for a long time, going back to my interest in Robert Smithson who often made works that were meant to decay and fall apart over time. Gamboni focused the interest more on public monuments and the politics of iconoclasm.

The publication feels more pertinent than ever in the wake of the ongoing debate about historic statues worldwide.

It is quite an extraordinary moment now in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, which is part of a long history in the US. Four years of Trump, and the coronavirus quarantine— that was the dry grass and George Floyd’s murder was the spark. Whenever you work on material like this that is dealing with really difficult moments of strife and unrest, you realise those moments are going to be relevant again and again, unfortunately. Yet I would not have imagined we’d be in this moment now when we made the exhibition last fall.

Your work Scaffold was embroiled in controversy when it was shown at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 2017. How did this effect your practice?

In Minnesota, the work was protested [by Native American groups] and we agreed to take it down. In some ways that whole situation got me thinking about this project in iconoclasm. Up to that point, I didn’t understand really how powerful symbols are and how powerfully they can affect people. That’s when I turned to David Freedberg’s book The Power of Images (1989), which is very much about this idea. A big part of how I look at iconoclasm now is structured around that experience [around Scaffold]. I experienced that iconoclastic impulse in real time.

What is in the pipeline for the Iconoclasm initiative?

I’m going to show these works at Blum & Poe gallery in Los Angeles in September, which will be an opportunity to promote the book. I’m also doing a new work, a video which will finish over the summer. It’s a two-channel video projection that takes this subject up through moving images.

It is great to now have the publication because it has a potential to reach a wider audience beyond the city of Detroit. To have the project contextualised with essay and information in one publication is a great advantage. I would love to see the book in libraries and in a range of bookstores, and obviously art bookstores. Getting it into schools is also an interesting possibility.

Iconoclasm by Sam Durant

• Iconoclasm, Sam Durant, Library Street Collective, 58pp, $35 (pb)