"The soil of the Cultural Revolution still exists in China,” the Chinese photojournalist Li Zhensheng said in one of the last interviews he gave before his death, in New York at age 79, of a brain haemorrhage.

Li, whose death was announced on 22 June, is recognised as the most dedicated, comprehensive and truthful chronicler of his country’s little-studied and deeply misunderstood Cultural Revolution.

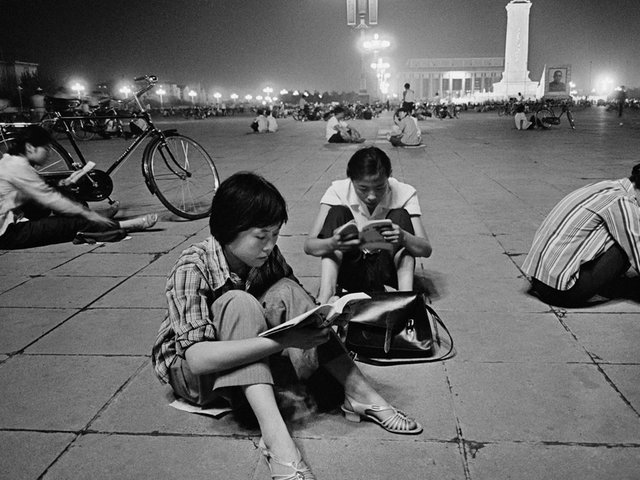

In words given via a family statement after his death, Li said he spent his life “striving to bear witness and document history”. His subject, unflinchingly, was the social and political turbulence of the Mao Zedong era, which saw tens of millions of Chinese citizens persecuted for “revisionism” - alleged alliances with China’s corrupt and defeated bourgeois.

Li is barely known in his native country. Yet the fact he was able to operate for so long pays testimony to his careful dissidence. Between 1966 and 1968, Li documented China’s mass upheaval as an official photojournalist for the state-endorsed Heilongjiang Daily, which allowed him unfettered observance of the seismic changes of a little-known province of north-eastern China.

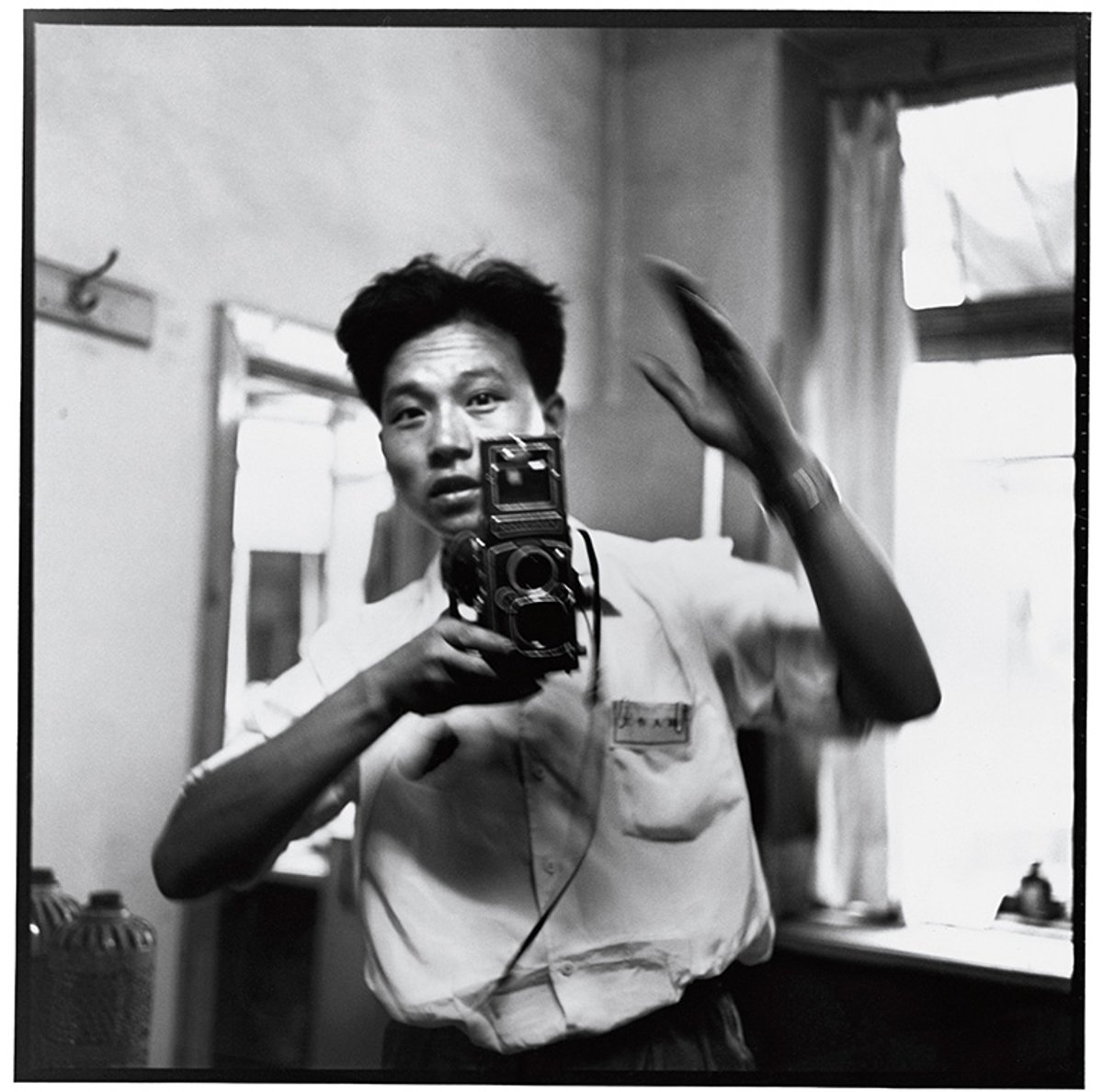

Li will be remembered in death for his double life—for the parallel photographs he began taking illicitly, fearfully, and entirely in secret at the age of just 25. In addition to the authority-sponsored propaganda, Li took around 20,0000 images without permission. He would stick around in the newspaper’s Harbin office until he was alone before, in the dead of night, hiding his negatives in secret compartments he had managed to fashion in his desk. He would then wait for the right moment to courier them home, where they lay concealed under the wooden floorboards of his bedroom.

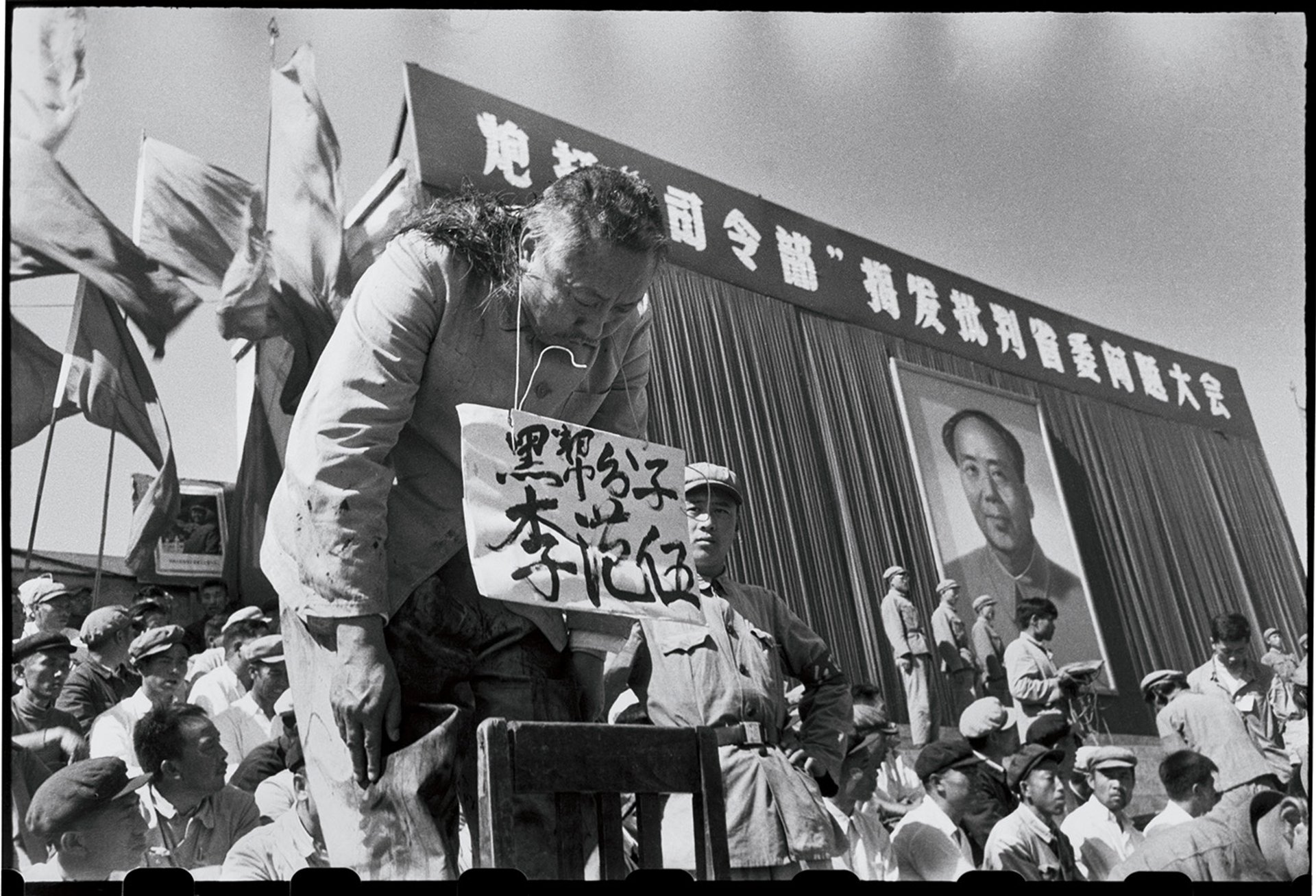

Black Gang Elements, Harbin, 1966 Credit: Li Zhensheng/Contact Press Images

The photographs aspired to show the complex, often dark and violent truths of the Cultural Revolution: the public humiliations, the arbitrary attacks, ruthless denunciations and all-too frequent executions.

His work includes the now-iconic image, taken in Harbin on 12 September 1966, of the Heilongjiang province Governor Li Fanwu in the midst of being made to bow for hours in public shame as his hair was violently pulled from his head. His crime: bearing too much of a resemblance to Chairman Mao.

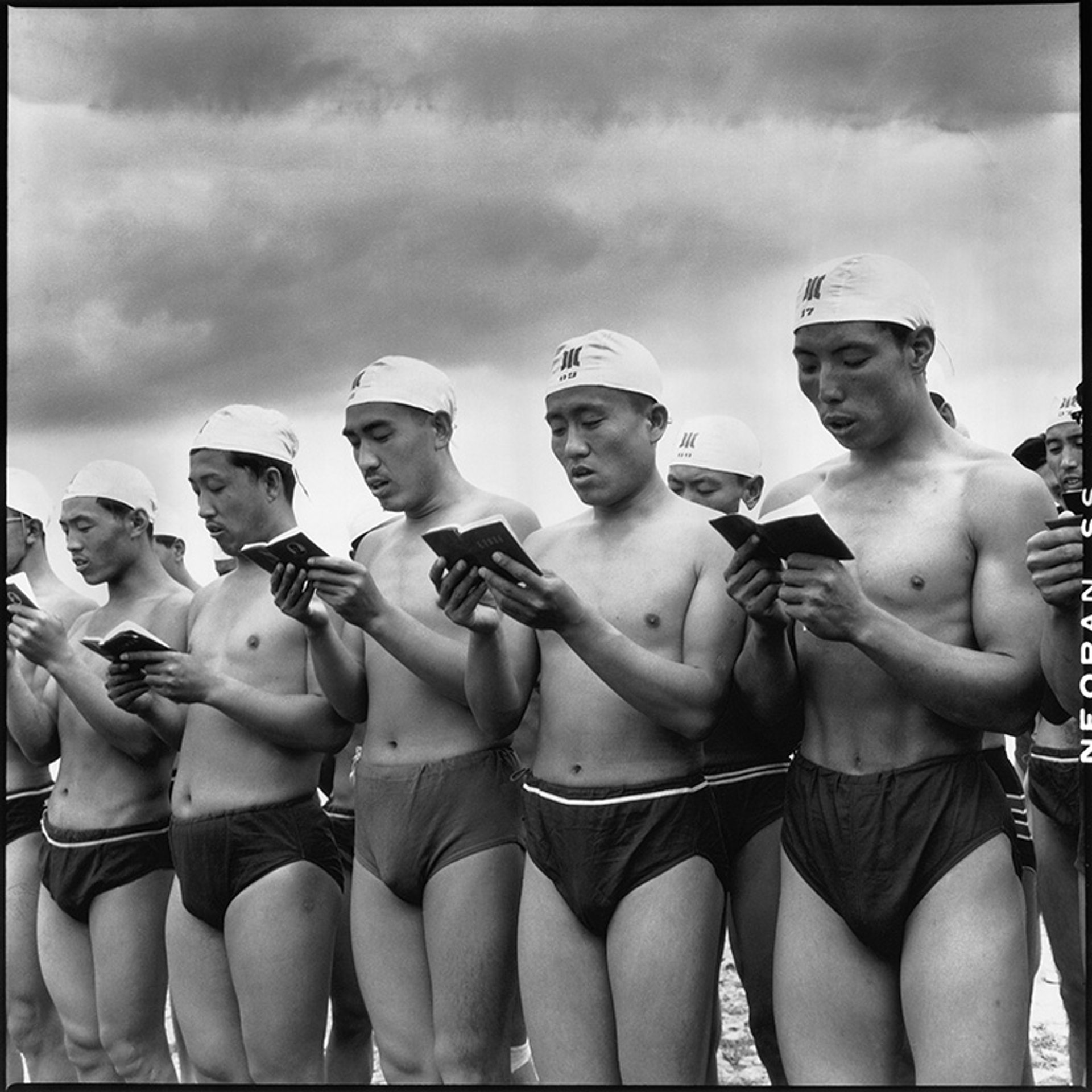

In July 1968, Li then photographed the countless men, naked but for uniform swimming trunks, studiously reading the pamphlet Mao Zedong’s Thoughts before their plunge into the Songhua River—an official commemoration of the time Mao Zedong swam in the Yangtze.

Swimmers read quotations from Chairman Mao for spiritual guidance as they prepare to swim the Songhua River, 1968 Credit: Li Zhensheng/Contact Press Images

As an official photojournalist, Li was required to wear an armband inscribed with the words "Red-Colour News Soldier". He appropriated the title when he was finally able to publish an edit of his clandestine archive in 2003. The resulting photo-book was printed in six languages, including in English by Contact Press Images, and would be exhibited in more than 60 countries. In July 2018, the first Chinese-language edition of the collection was published in Hong Kong, but Li Zhensheng died without ever seeing the book on sale in his homeland.

His secretive work may not have seen the light in his lifetime, but the Chinese state will struggle to keep Li’s documentation of the Cultural Revolution hidden forever.