The artist-led campaign 'Where is Kajol?’ has launched an online exhibition of the work of Shafiqul Islam Kajol, the renowned photojournalist currently imprisoned under Bangladesh’s notoriously draconian Digital Security Act.

After disappearing without trace or word to his family on 10 March, Kajol was discovered 53 days later, on 3 May, in a prison in Benapole, a small, rural town close to the Indian border and approximately 250km from his home. He remains in remand in the over-crowded Jashore Central jail and is at heightened risk of contracting Covid-19, his family say.

Kajol was last seen on CCTV riding his motorbike from his office in Meher Tower in Hatirpool, a busy marketplace in central Dhaka. Earlier CCTV footage obtained by Amnesty International shows a group of men tampering with Kajol’s parked bike as he worked in the office before tailing him after he left. Police registered a complaint from Kajol’s family on 11 March but flatly denied having him in custody.

While it is not yet clear how Kajol ended up in Benapole, or what has happened to him in the more than two month interim since he was last seen, Amnesty International has alleged this is a case of enforced disappearance; an act of blatant opposition-silencing that has become synonymous with Bangladesh’s ruling Awami League party since it took power in 2009 under the leadership of the now 72-year-old female prime minister Sheikh Hasina.

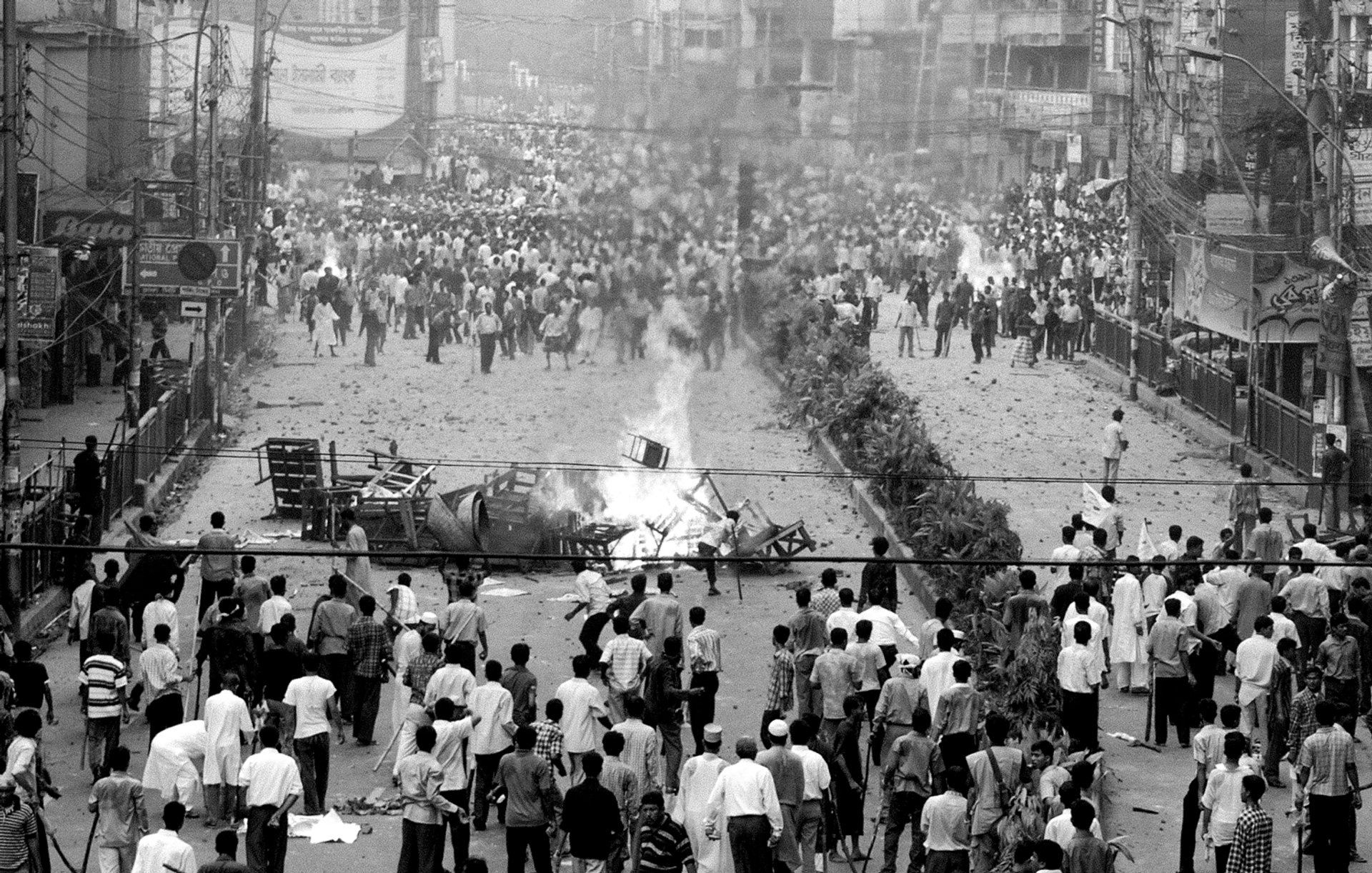

© Shafiqul Islam Kajol, courtesy Last Man Standing/Where is Kajol

Kajol is the editor of the mainstream Dhaka fortnightly newspaper Pokkhokal. On Facebook, he recently published an investigation alleging that up to 30 influential bureaucrats and politicians, including members of parliament, were involved in a prostitution racket and sex-trafficking ring in downtown Dhaka.

The day before his disappearance, an Awami League MP filed a case against Kajol and 31 other journalists under the country’s Digital Security Act, which became law in 2018. The group was charged with “spreading confusion by publishing false, fabricated and defamatory news.” Other journalists charged were using their platforms to report on alleged embezzlement of aid for coronavirus victims in rural Bangladesh.

In the early hours of 3 May, a duty officer informed Kajol's son, Monorom Polok, that Kajol had been arrested for “trespassing” along the borders of Bangladesh without a passport or visa. He was briefly granted bail for that offence before being arrested again on Digital Security Act charges. If found guilty, Kajol faces a possible seven years in prison.

© Shafiqul Islam Kajol, courtesy Last Man Standing/Where is Kajol

Bangladesh currently ranks 151 out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. According to the International Federation for Human Rights, there have been more than 1,000 cases filed under the Digital Security Act since it was introduced in 2018.

More than 550 people have disappeared in Bangladesh since 2009, when Awami League came to power, according to the human rights monitor Odhikar. The Bengali words ‘Goom’ and ‘Ophoron’ translate as ‘disappeared’ and ‘abducted’, and are commonly used in Bangladesh to refer to those who have vanished.

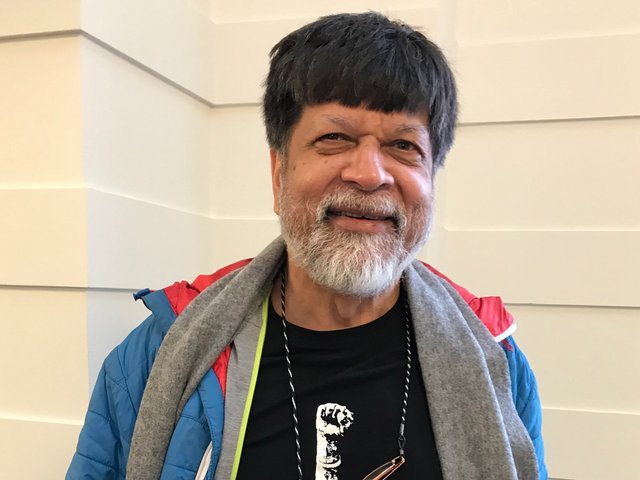

Led by Kajol’s son Monorom Polok, a 20-year-old student at Jagannath University, the campaign has gained support from multiple artists from across Bangladesh society. One of the people lending his support to Kajol's case is the Bangladeshi photographer and activist Shahidul Alam, a recent Prix Pictet nominee and himself a victim of the Digital Security Act. Artists from across Bangladeshi society and around the world have created works, hosted live discussions and shared creative forms of protest with the hashtag #WhereIsKajol, including live poetry recitations by Kajol’s 11-year-old daughter, Poushi.

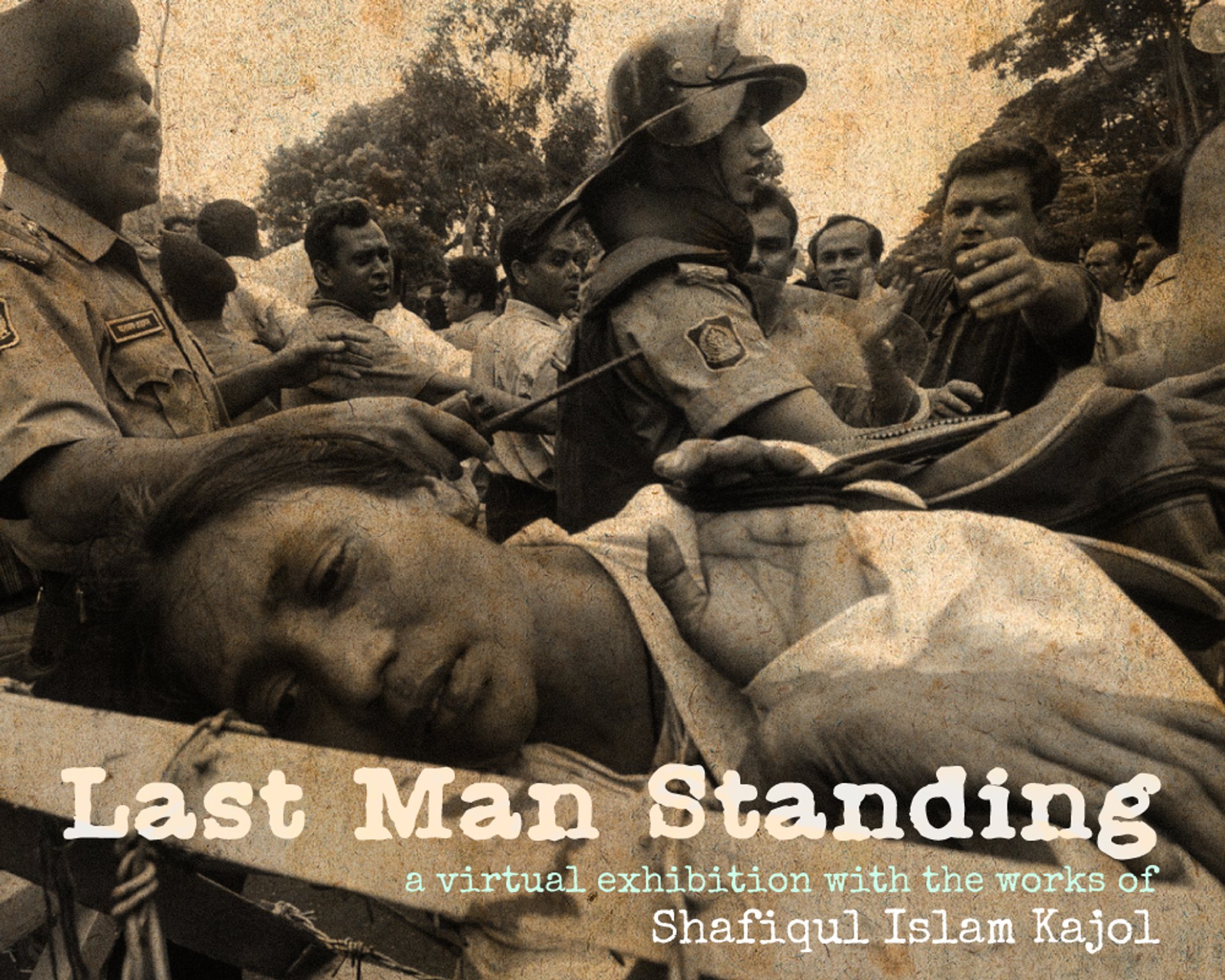

The exhibition poster for Last Man Standing © Shafiqul Islam Kajol, courtesy Last Man Standing/Where is Kajol

“The Bangladesh government has now dropped all pretence," Shahidul Alam has said on his social media channels. “Any form of dissent, protest or difference of opinion is met with disappearance or extrajudicial killings. It appears that anything short of sycophancy is a threat.”

Shahidul also called for more voices from the artistic community to add their weight to the campaign. “The fact that mainstream artists and intellectuals continue to stay silent is deeply disturbing,” he wrote. “The time will come when you will need to defend your silence to the average Bangladeshi. People will not forget your betrayal.”

The online exhibition, titled Last Man Standing, shows Kajol’s personal photography, as well as his work as a photojournalist for the Samakal, Jai Jai Din and Bonik Barta papers. It opens with a tribute to the still imprisoned photographer: “Kajol’s disappearance is perhaps the price of his uncompromising lens towards social distortion. We demand the return of the last man standing.”

For more information and to view the exhibition, visit the Where is Kajol public group on Facebook.