What can self-isolating art historians do in a pandemic? Even the most ardent student of art might struggle to define themselves as an essential worker right now. Nor can we do much other than admire those tackling the virus on the frontline, be it in hospitals or supermarkets, and be immensely grateful to them. I do believe, however, that from an art historical point of view, there is still some good to come of all this.

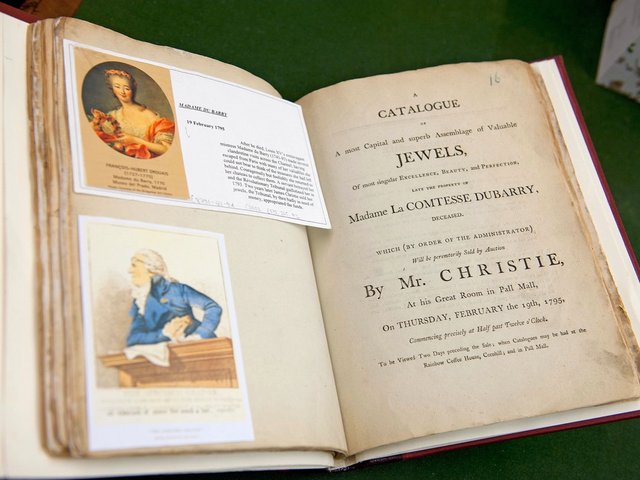

For the next few months, art historians the world over will be putting their enforced period of seclusion and study to good use. I am already looking forward to all the new research, articles and books that will emerge by the end of the year. The good news is that many of the tools of our trade remain unaffected by the pandemic. To pick just three long-established websites: the Internet Archive allows you to search even the most obscure publication for that tiny nugget of crucial information; the Getty Provenance Index allows you to search almost two million sales records in seconds; and image libraries such as the RKD’s invaluable collection of historic photos of Dutch art are available digitally too.

Indeed, the art historian’s need to work remotely has prompted many publishers and libraries to extend online access. The latest issue of the Burlington Magazine is now free for everyone to read. The digital library JSTOR has increased its free access from six articles a month to one hundred. In some ways, being an art historian now is easier and more productive than it’s ever been. What would have taken previous generations of art historians weeks to discover in multiple libraries and archives, I can find from my desk in rural Scotland in just minutes.

Of course, before I get too carried away, there remains the minor issue of not actually being able to see any art, at least in person. But here the modern art historian can call on another gift not available to their predecessors: the online collection. Many museums have spent the best part of two decades building highly complex databases with not only images but detailed catalogue entries. Some are truly the Rolls-Royces of their kind. In my view, the Royal Collection’s is excellent. Another is the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which not only has a detailed online database but also scholarly exhibition catalogues going back to the 1870s.

My favourite online collections are those that have been lovingly compiled by the same individual curators since their creation. Hugo Chapman, the keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum (BM), has been adding information to the BM’s catalogues since 1995. I seem to find myself indebted to him at least once a week as I scour the BM’s excellent database. That said, some museums seem to have missed the invention of the internet altogether; the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp still has no online collection site, even though the museum itself has been shut for renovation since 2011.

Of course, art historians don’t normally have to juggle their work with home schooling, or an even greater degree of financial precarity than they normally face, to say nothing of dodging potentially lethal viruses. But it may be some solace that amid all the anxiety we are able to work in a field filled with beauty and wonder, even if it is only accessible—for now—through a screen.

- Bendor Grosvenor is an art historian and broadcaster