If I had a pound—or for that matter a dollar or a euro—for every time I read or hear someone say that we must turn this corona-virus crisis into an opportunity, then I probably wouldn’t need to try to restart my career as a freelance writer—“when this is all over”. But we must use this enforced pause to do some thinking. The damage that is being done to artists, and to the businesses and institutions they gain their living from, is devastating. In the UK the four arts councils have come up admirably quickly with emergency funding measures that are intended to help sustain both individual creative practitioners, and museums, galleries, libraries and performing arts organisations, all of whom have seen their incomes disappear. They have no idea when, or if, they might return.

This emergency package goes alongside the other economic measures the British government is taking and it is very welcome. But we don’t just need a rescue.

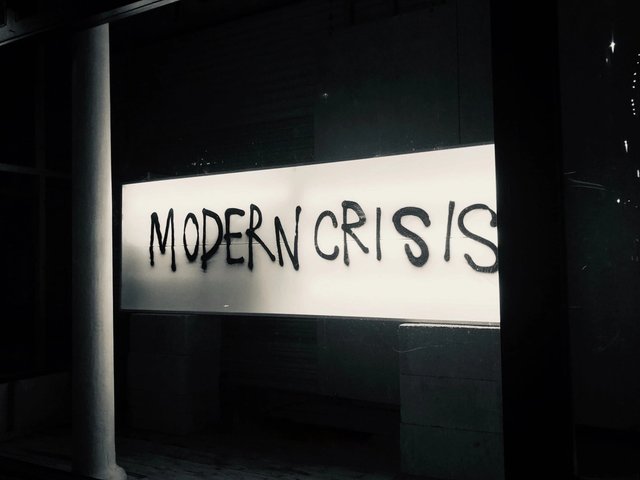

We need a rethink.

We have learned to think of the arts as part of “the creative economy”. But what does this really mean? The Creative Industries Federation will tell you that it is something worth £100bn to the UK’s economy, that it exports £46bn in goods and services, that it is growing at twice the rate of the rest of the economy, and employs more than two million people. Or at least it did. Such is the structure of this economy, consisting mainly of small, under-capitalised businesses and uncertainly-employed self-employed, its firms are going bust and its workforce is out of work. Even before this crisis, there was another word for this workforce: the “precariat”.

The arts are only part of the creative economy, but are vital to it. When even the National Theatre has to appeal for donations, you know that the arts are much more exposed than some of the so-called industries that attach the word creative to their name. We don’t expect the National Theatre, Tate, the South Bank Centre or the British Museum, with their London buildings and metropolitan power, to fold, but everywhere theatre companies, galleries, orchestras and museums are in danger of closing—or already have. The precariat is having to sign on the dole.

The creative economy was an invention of the 1980s. It began as an argument for the economic importance of the arts at a time when even modest public funding was under threat from Mrs Thatcher’s government, but the argument modulated into one about the importance of cultural production and consumption in a post-industrial economy—that post-industrial economy being another result of Thatcher’s neo-liberal policies. It was understood that artists, writers, composers, directors and performers employed in the significantly titled “not-for-profit” sector were in fact creating profits, directly through copyrightable ideas and images which can then be commercially exploited, and indirectly in terms of the cultural consumption they generate in the form of local and international tourism. The argument was enthusiastically taken up by declining cities like Glasgow, which badly needed an image makeover. Liverpool has similarly benefited from the “City of Culture” process.

There are a number of problems with this: it is doubtful that Glasgow’s “Merchant City” has done much for Easterhouse, or that the virtual privatisation of Liverpool city centre has benefitted Knowsley. Arguably, the money could have been better spent on renewing the social infrastructure rather than creating a fashionable façade. But the consequence of arguing for the economic importance of the arts—even when it is in one’s own interest—is that the arts become more and more a commodity like any other. Driven by the neo-liberal principles that for the past 40 years have framed thinking about the economy as a whole, cultural institutions that were consciously set up without profit in mind have been made to seek ever greater profits. Because their public support has indeed been progressively driven down as a proportion of their turnover, arts organisations have had to do deals with ethically and environmentally dubious commercial sponsors. For the same reason, museums have become shopping malls, theatres and concert halls have put ticket prices out of the reach of many of the people that public funding was intended to encourage to participate.

Notwithstanding the fact that they exist within a market economy, the arts are not, ultimately, a commodity. They are an offering. They offer meanings that exist outside the cash nexus. They offer delight, they offer hope, they offer consolation. As I have long argued, there is a difference between value in exchange and value in use, between cash value and cultural value. We have to think of the arts as part of the public realm, that space where private and public interests meet and where their conflicts can be resolved, where the local can find accommodation with the national, and where there are institutions that are not driven solely by the profit motive, but by the idea of a greater public good. When we attend a performance or visit a gallery, we become more than individuals, we become the collective sharers of a common imaginative space.

Nonetheless the creative industries, which are more to do with consumption than creativity, do exist, and have to be taken seriously. For one thing, like other industries before them, they have created their own proletariat. If we accept that the arts do make an economic contribution, then we need to better understand the gearing between an individual act of creation and the industrial mechanisms devised to exploit it. Precisely how do insecure, underpaid, marginal people—artists—make such a contribution to this £100bn economy, and how can they be better rewarded?

Rethinking the relationship between our publicly-funded institutions and the private sector will not harm the creative economy, in fact it will stimulate it, not by commanding creativity, but creating the conditions in which it will flourish. That means supporting the not-for-profit sector for its own sake, because it has a social role that is far more important than its economic one. The government clearly values the creative economy, but is blindly restricting its growth at the roots, in public education, where creative thinking and expressive practice is being squeezed out of the system. The language of the creative economy drives us to use the discourse of “investment”, but education is about the liberation of the mind.

In the light of the decisions taken since this crisis hit, the British government appears to have experienced a Keynesian conversion, subsidising everything in sight. It is ironic to recall that the prophet of state economic intervention, John Maynard Keynes, was also the first chairman of the Arts Council of Great Britain. But I fear that our rulers will revert to their neo-liberal principles, and that having weakened the whole of the public sector with ten years of austerity, it will claw back its largesse by imposing more. And this time, no one, not even the Arts Council, will have any reserves.

We may be facing the equivalent of a forest fire, but, thinking positively, that clears the undergrowth, and lets the light in. This is an opportunity to reimagine the infrastructure of the arts, especially at the local level, away from London and Whitehall. We need to think about the 80% or more of the population who are not regular enjoyers of what the publicly funded arts have to offer. We must create the circumstances where arts organisations can grow until they can stand on their own two feet, and then not be burdened with the expectation of extraneous outcomes and spurious metrics. We should worry less about the creative economy, and rebuild the public realm. From the ground up.

• Robert Hewison is a British cultural historian