Small French museums were this week given a green light from the government to reopen their doors from 11 May, two months after they closed. But if the lockdown has cut them off from the public physically, it has forced many institutions to ramp up their digital presence, with some plunging into social media for the first time.

The Centre Pompidou in Paris, like other large museums, will remain closed until at least 2 June. In the meantime, it has transformed its website into a dense content platform while a new design is under development. “Since we are not selling tickets, we were expecting the number of online visitors to plummet, but it has only increased,” says the head of the museum’s communication and digital department, Agnès Benayer.

The Pompidou podcasts in French and English have had eight times as many listens since the closure began, reaching a peak of 35,000 in one week. Traffic to the YouTube channel is up 60%, with 12,300 subscribers. And last week, the museum launched Prisme7, a free video game featuring 40 works from its modern and contemporary art collection.

The Paris Musées network of 14 municipal museums, from the Petit Palais to the former home of Honoré de Balzac, has opted for interactivity. Thanks to quizzes, photo-sharing challenges and other digital “events” on their social media channels, their followers have grown considerably, up 33% on Twitter and more than 150% on Facebook.

The Musée Marmottan-Monet, which did not have on Instagram account until last year, has nearly reached 8,000 followers, boosted by a series of video interviews with the museum’s director Marianne Mathieu.

The digital boom goes beyond Paris and its major institutions. The director of the Musée Paul Valéry in Sète created a YouTube channel four weeks ago; the first video it posted hit 1,200 views in a day.

The museums of Allier, in the Auvergne region, have doubled the frequency of their Facebook posts using the hashtag #culturecheznous (culture at home), launched by the French ministry of culture. Rather than replacing the experience of visiting a museum, the aim is “to make people want to come as soon as we reopen”, says the communications manager Delphine Desmard.

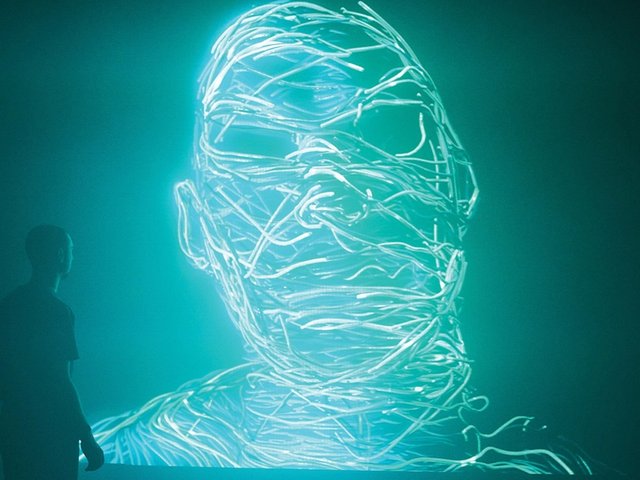

One French museum has experienced skyrocketing attendance levels during the lockdown. The Universal Museum of Art (UMA), a startup launched in 2017, is billed as the world’s first virtual museum, with free online exhibitions including Leonardo da Vinci, street art and cats in art history. With up to 20,000 unique visitors a day since mid-March, it could become one of the 20 most visited museums in France by January 2021, according to its chief executive Jean Vergès.

Unlike the Google Arts & Culture website, which hosts high-resolution images of works from partner museums and 360-degree Street View tours of their buildings, each UMA exhibition is a simulated 3D space designed with the help of architects and curators. A forthcoming show, From the Renaissance to the Early 20th Century, involves around 60 French museum partners—the highest number so far.

Although UMA exhibitions are free to access, production costs are covered by charging fees to partner institutions. Organisations interested in hosting VR experiences, such as hospitals and shopping centres, also pay to access the UMA database.

For bricks-and-mortar museums, however, there is no business model for digital expansion that would compensate for the loss of paying visitors. Charging for online content is not an option for now. “Our mission is to make art as accessible as possible, adopt and adapt to digital tools,” says Agnès Benayer at the Pompidou. “Maybe it’s time we thought of virtual and in situ together and no longer in opposition.”