In spite of her legacy, Diane Arbus has received relatively little exposure in Toronto (or in Canada altogether) where exhibitions are concerned. Since her premature death in 1971, Arbus’s works have been routinely displayed in shows large and small around the globe, but she has not been the focus of a Canadian show since an exhibition at the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation in Toronto in 1991. The city’s Art Gallery of Ontario is now playing host to a major Diane Arbus retrospective. The reason? In 2016, the efforts of numerous donors allowed the museum to acquire 522 of the artist’s photographs, making its Arbus collection the largest in the world after that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“It’s something like walking into a crowded room of people you haven’t met before,’’ said curator Sophie Hackett of Arbus’s photographs at the press preview for the exhibition this week. “You’ll be attracted to some, you’ll be curious about others,” and “others … you might want to avoid.’’ Actually there are three main rooms in the show in which 150 photographs from the entirety of Arbus’s career have been arranged chronologically. With the exception of a self-portrait Arbus took of herself in 1945 while pregnant with her daughter Doon—the show’s starting point— the retrospective begins in 1956, when the artist left the fashion photography business she ran with her husband to pursue her craft in earnest, and ends in 1971, the year she committed suicide.

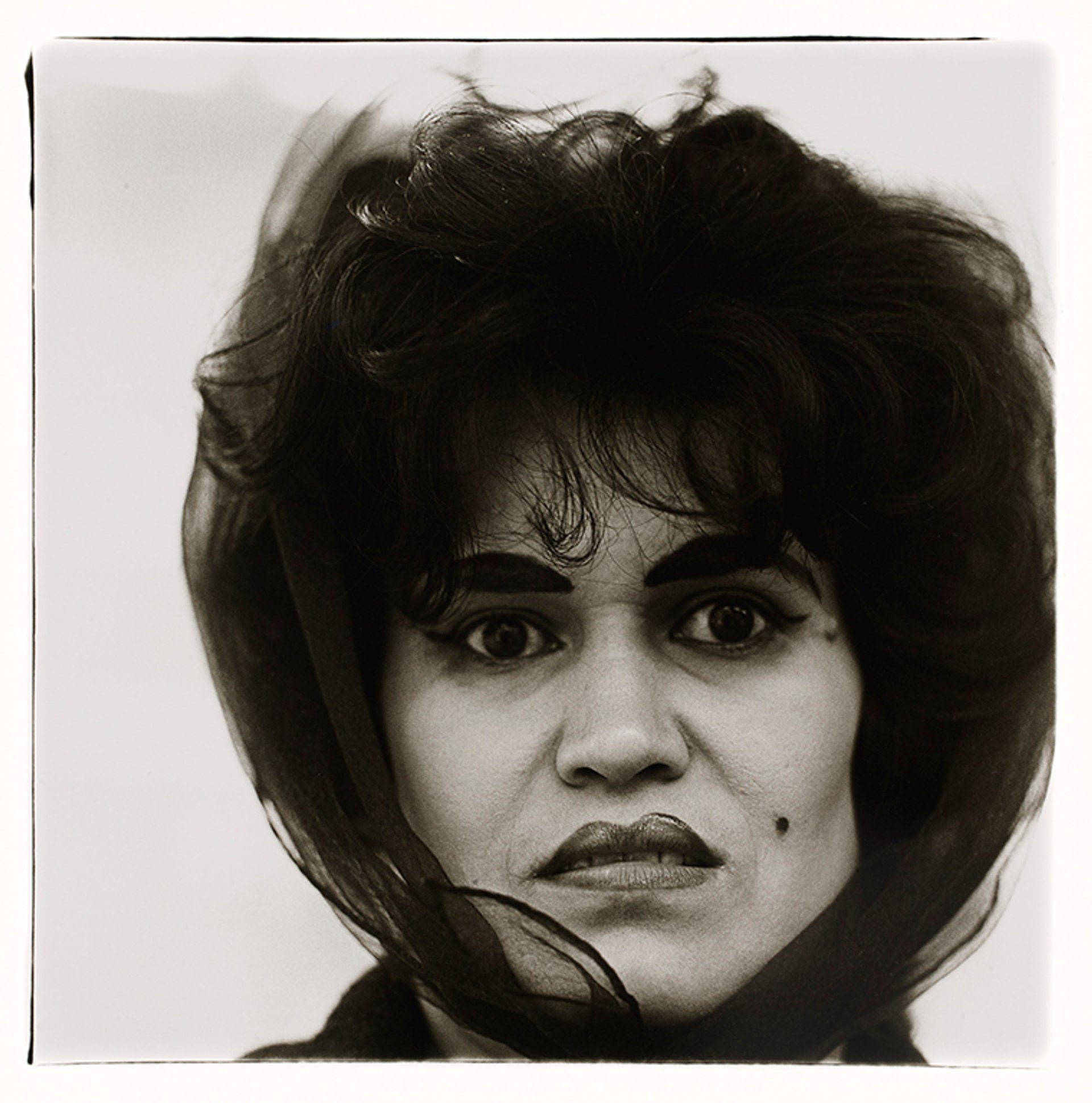

The Art Gallery of Ontario bills the show as the first to present images from the full sweep of Arbus’s career chronologically. The progression is indeed important to the experience as it allows viewers to examine how Arbus matured as an artist and how the nature of her photographs changed throughout the years, as well as when she began working with different film formats. Until 1962, Arbus captured her subjects on grainy 35mm film and that year started using a Rolleiflex camera with a medium-format square negative. In preparation for 1967’s New Documents, her first major solo exhibition, she began making larger prints. This camera’s more square format arguably lent itself well—if not better—to the more jarring and intimate photographs she took from the mid-1960s until her demise. Some of Arbus’s most iconic works, such as Identical Twins (which famously inspired the twins in Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film The Shining), Puerto Rican Woman with Beauty Mark and Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park — all of which are in the show—were shot on a Rolleiflex, and it’s hard to imagine them having even nearly the same effect in a smaller format.

Diane Arbus, Puerto Rican Woman With a Beauty Mark, NYC, 1965 Gift of Phil Lind 2016; © Estate of Diane Arbus

The aforementioned individuals comprise the “attractive’’ people in the exhibition, to return to Hackett’s observation. Aside from them and icons like Marcello Mastroianni, James Brown, and Christopher Isherwood, whom Arbus photographed for various mainstream magazines such as Esquire, one can expect, for the most part, to see dwarves, drag queens, nudists, dominatrixes, sword swallowers, bearded ladies and other such characters that evoke “all the fat-skinny people/And all the tall-short people/And all the nobody people’’ David Bowie sang about in his apocalyptic song Five Years. As the late photographer David Vestal once noted in reference to these characters in Infinity Magazine, though, Arbus “does not emphasise their ‘abnormal’ or ‘freak’ character. Instead, she concentrates on showing—with seriousness, dignity and sympathy —how much they have in common with the ‘normal’ people around them. They may just be more open and direct, more vulnerable, more visibly human than most people.”

While by and large, the so-called ‘‘freaks’’ that Arbus photographed were obscure, some are recognisable. The contortionist Joe Allen, for instance, appears in a 35mm photograph from 1961, while photographs of Hezekiah Trambles—better known by his stage name, Congo the Jungle Creep—can be seen in a pristine 1960 edition of Esquire. In addition to a poster of the “Human Corkscrew” Joe Allen, one of Arbus’s photographs of Congo adorns the cover of the Rolling Stones’ seminal Exile on Main Street album from 1972 (which, interestingly, was shot by Arbus’s friend Robert Frank a year after her death).

Accompanying the many photographs and assorted magazines on display are sundry ephemera that further help narrate Arbus’s story. In the section dedicated to the artist’s images from the mid-1950s is a blown-up photograph of one of her notebooks. Elsewhere, one can read an enlarged facsimile of an application that she successfully submitted in 1962 for a Guggenheim fellowship. Even though Arbus once complained of never having felt adversity—'‘one of the things I suffered from’’, she said—such exhibits show that finances were still a concern for her.

An untitled work by Diane Arbus from 1971 Anonymous gift, 2016; © Estate of Diane Arbus

In more ways than one, this retrospective—which will later travel to Montreal, Vancouver, and Calgary—has much to offer photography connoisseurs as well as lay audiences unfamiliar with Arbus’s oeuvre. That said, it is the latter whom—in a country like Canada, which still has a way to go before it can be spoken of as an art destination— it may benefit the most. ‘’Diane Arbus is unbelievably good, incredibly complex,’’ says the Art Gallery of Ontario’s director and chief executive, Stephan Jost, who spoke animatedly about the museum’s goal to attract and engage with younger generations during the press preview. “And I believe that it’s very, very difficult to talk about 20th-century art without talking about Diane Arbus smack in the middle of that. And I’m not [only] talking about the history of photography—I’m talking about art history.’’

Diane Arbus: Photographs, 1956 – 1971, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 22 February–18 May