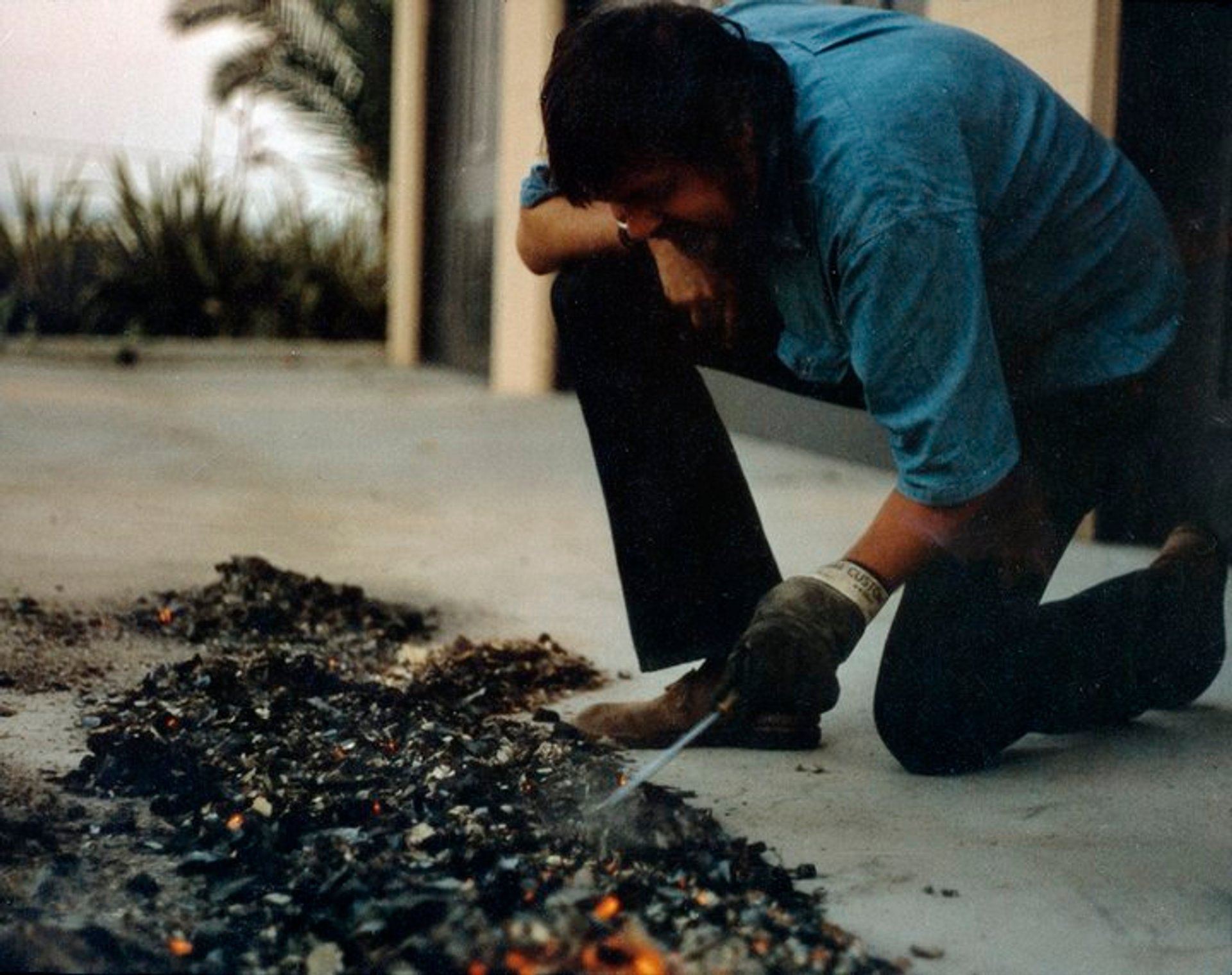

In our examination of lost art, we tend to assume that art that is destroyed is, by definition, tragic, upsetting to art lovers, collectors and the artists themselves. But there is a vein of art that was made only to be destroyed. Art “born” with its death warrant signed. In such cases, art lovers might sigh for not having been able to see the work prior to its obliteration or bemoan the fact that the work was deemed disposable by the artist. We praise Max Brod, Franz Kafka’s friend, whom Kafka charged with burning all his manuscripts after Kafka’s death. Brod decided that it was for the collective good to go against his friend’s wishes, and instead Kafka’s texts were published—and are considered among the greatest works of literature ever written. And in 1970, when the late contemporary artist John Baldessari turned to conceptual art, he famously burned all of his earlier figurative and abstract work in a symbolic “death” of his artistic body. The resulting installation created from the ashes and called Cremation Project, remains in the artist’s estate.

John Baldessari, The Cremation Project (1970) © John Baldessari

The practice of artists destroying their own work is almost exclusively a phenomenon of the modern era, however. Prior to the 18th-century rise of galleries and the art market, and especially before the industrialisation of paint production, when pigments could finally be purchased for reasonable sums of money in tubes or canisters, raw materials for paintings and sculptures were so expensive that it would have been foolish to destroy them. Works were also almost exclusively made on commission; they did not sit in an artist’s studio until a buyer or exhibitor could be found. So aside from irregular incidents, such as Botticelli offering his own paintings to Savonarola’s Bonfire of the Vanities in a fever of piety, artists before the modern period could not afford to ruin what they had made.

Artists in fact very often preserved materials by reusing them. During the Renaissance, vellum and paper for drawing were not inexpensive; they were not nearly as costly as painstakingly planed and joined wooden panels, but they were nevertheless a commodity not to be disposed of profligately. As a result, artists frequently filled paper and vellum with sketches, front and back, on any blank space. Canvases might also be reused, and modern technology permits us to look beneath the top layers of paint, to view what lies beneath.

Studying paintings with x-rays, ultra-violet and infrared lights can reveal pictures, buried but still lively, beneath the surface layers of paint. If light causes these upper layers to fade, the underlying pictures can ghost to the surface, gradually appearing as hazy outlines called pentimenti, as can be seen in the painting of a child suckling at the breast of his naked mother, beside an ox and lamb (perhaps a sort of Nativity scene), found beneath Pablo Picasso’s famous Blue Period Old Guitarist (1903-04). In such cases, technology is the key to summoning up these revenants.

While most cases of artist-destroyed art can be attributed to a certain level of vanity or perfectionism, there were other motivations. When Ingres (1780–1867) remarried, his new spouse did not take kindly to a spectacular nude of his deceased first wife, which remained in his studio. The painting disappeared, perhaps disposed of, perhaps passed on to another by the artist, in the interest of marital concord. An 1852 daguerreotype photograph of the painting in his studio is all that remains of a masterpiece.

Heather Benning, The Dollhouse (June 2007)

Then there are artists who create a work, then determine to destroy it in the name of creating a new work. In 2007, the Canadian artist Heather Benning (b.1980) built a life-sized dollhouse from an abandoned farmhouse. Over the course of 18 months, she renovated the house, creating an idyllic structure with picture-book rooms and one entire side of the building missing and replaced by glass, so the rooms could be easily seen. The Dollhouse was a beautiful object, surreal in its magnification of a child’s toy, an interesting take on our curiosity about other people’s lives, at a time when reality TV was popular. But the foundations of the house, which dated to around 1968, were unstable by 2013. Recognising the inevitability of an eventual collapse, Benning decided to turn this potential disaster into a new work of art. While beautiful photographs of the house remain, the building itself does not. She set fire to it that year, in a new work entitled Death of the Dollhouse.

The colossal Trump-like wooden sculpture by Tomaž Schlegl installed in the Alpine village of Sela in Slovenia (about an hour away from where First Lady Melania was born) made international headlines when it was first unveiled, on 29 August 2019. But some of the more conservative locals were unimpressed—they were concerned that it would bring ridicule, not recognition, to their idyllic village. It was offered domicile, as Slovenian newspapers joked, by the nearby town of Moravče. It arrived there in early January 2020. A few days later, the statue made international headlines again, when arsonists burned it to the ground in an act of vandalism.

The funny thing is that the artist who designed the statue was completely delighted by its destruction. The artist is a friend who lives just a few miles away from me in the Slovenian Alps. When he first conceived of the statue, he told me and my wife about it while sitting on our porch, eating peanuts and chain-smoking. Schlegl always planned it to be a temporary work. The idea was to burn it, ritually, in a bonfire on Halloween 2019—a sort of Burning Man festival meets the Salem witch trials. But the locals got nervous about burning Trump in effigy (they were already nervous about having a statue that seemed to mock the short tempered US President at all). Schlegl felt that the conceptual work was not complete without its flaming end.

A wooden sculpture resembling US president Donald Trump was lit on fire, in Moravce, Slovenia, on 9 Janurary 2020 Municipality of Moravce

And so, reluctantly for the artist, a new plan was hatched, to move the statue elsewhere and let it remain “alive”. The mayor of Moravče saw this as an opportunity to raise the visibility of his town and draw some tourists. So, the statue was brought from Sela to Moravče, about 13 kilometers away. There was a grand ceremony to install it. Within days, it was ashes.

Schlegl wanted the statue to be burned to symbolise the destruction of populist, neo-fascist-type leaders in general. The actual rationale for the act appears to be far more prosaic. At the unveiling ceremony, several people overheard some local teenagers talking about getting gasoline in order to burn the statue. It was likely an idiotic prank undertaken by bored teens to get some attention. But they inadvertently managed to spark a debate and world headlines. And whatever the impetus of the arsonists, the artist is delighted that his conceptual work is finally done.