Sotheby’s fielded a well-paced contemporary evening sale last night, much on a par with last year’s result despite having 20 fewer lots, suggesting the British contemporary art market has, for now, stabilised.

“Against the headwinds of Brexit, the election and Sotheby’s changing hands, the new Sotheby’s is very much up and running,” Olly Barker, the firm’s European chairman, said after the sale, which totalled £79.2m (£92.5m with fees), just north of its low estimate, compared with £77.9m (£93.3m with fees) last year.

As Sotheby’s steadies itself under the new guard, there can be no doubt that the art market pecking order is also undergoing some revision.

Outliers including Banksy and Maurizio Cattelan made more of a splash than David Hockney’s star lot, chiefly due to bidding from US and Asian clients. Banksy’s Vote to Love (2018), an altered Vote to Leave placard in which the “o” of love has been replaced by a heart-shaped balloon, was caught in a three-way phone tussle before selling in the room to Bartow Morgan, the chief executive of the US BrandBank, for £950,000 (£1.2m with fees), more than double its low estimate.

So why would a Georgian born and bred banker buy a cardboard placard about Brexit? While the UK has Brexit, Morgan, who has donated to the Republican Party in the past, simply says, “We’ve got Trump.” Ultimately, it seems, his motivations were much closer to home: “What can I say, my kids love it.”

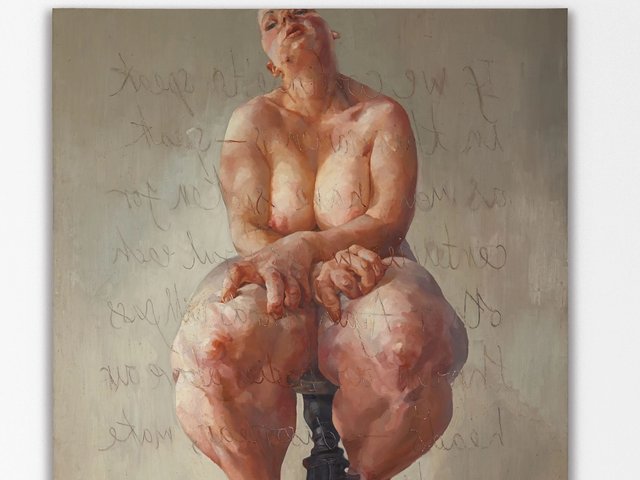

David Hockney's The Splash (1966) sold to its guarantor for £21m Courtesy of Sotheby's

An expensive piece of history many in the UK would rather not be reminded of, the Banksy was first shown at London’s Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 2018, where it was “sardonically priced”, according to Sotheby’s, at £350m, a reference to the “much-lampooned” Vote Leave bus which claimed Brexit would save the NHS £350m a week.

From much-lampooned to much-talked about, the ripple effects of Cattelan duct-taping a banana to a wall at an art fair and giving it a $120,000 price tag are still being felt. According to Barker, the Italian artist has been going through “a market low”, but is now “bouncing back”.

After an extended ping pong match between Yuki Terase and Patti Wong, Cattelan’s disturbing 2007 installation of a life-sized girl dressed in a white nightgown with hands nailed to wooden boards above her head went to Terase for £1.25m (£1.5m with fees)—double its low estimate. Asian buyers accounted for eight of the 46 lots, Sotheby’s said.

Despite the excitement, however, the returns on the Cattelan are not huge. The consignor bought it in 2017 at Christie’s in New York for $1.5m.

Fresh faces were also in demand, even if their works were not so fresh to market—usually a crucial factor for these London sales. Most notable among them was Julie Curtiss whose Witch (2017) sold for £130,00 (est £50,000-£70,000) having been acquired by the consignor at New York’s Spring/Break Art Show in 2017 for a comparably low $1,400. Curtiss has just been taken on by White Cube.

By contrast, big-ticket items failed to elicit a great deal of interest. Hockney’s quintessentially Californian pool painting, The Splash (1966), sold on what appeared to be a single phone bid, possibly to its guarantor, for £21m (£23.2m with fees), just tipping the £20m low estimate. According to Bloomberg, the canvas was consigned by the Hong Kong billionaire Joseph Lau who bought it at Sotheby’s in 2006 for £2.9m.

The Splash was one of 11 lots to be guaranteed by a third party, including two that Sotheby’s managed to convert at the last minute from in-house to third party: an Yves Klein body painting (est £6m-£8m) and a lemon curd-hued Cecily Brown canvas (£900,000-£1.2m).

According to the London dealer and Hockney specialist Ivor Braka, it was the guarantee that chiefly prevented the Yorkshire artist’s painting from reaching its potential. “If you push for a very high guarantee, as in this case, you kill off a lot of the interest before the event and the picture tends to sell for the guarantee price,” he says. If the work had been estimated around the £12m to £15m mark, “it could have easily, with competitive bidding, reached £30m”.

Other factors going against the painting included its relatively small size, around 36 inches square once stripped of Hockney’s framing devices. As Braka says: “People who wanted a very dramatic and commanding image with a lot of wall power, to use a horrible phrase, this wasn’t it.”

Another Modern British master, Francis Bacon, also failed to ignite the room. His Turning Figure (1963) did not carry a guarantee and sold on its low estimate for £6m. Braka describes it as a “first-class picture” but was put off from bidding by the fact that it is “essentially a collage”; Bacon razored the figure from another painting and stuck it on this canvas. “People are very wary of anything that deviates from the norm, which is why the price was not perhaps where you thought it should be,” Braka says.

Perhaps prudently, pre-sale jitters got the better of the consignor of another high value lot without a guarantee—a vivid abstract work by Gerhard Richter estimated at £6m to £8m, which was withdrawn immediately before the sale. A further three lots were unsold.

Overall, only five lots tipped the £5m mark and only one, the Hockney, went above £10m. London has long played second stringer to New York in terms of big-ticket items, but last night that rang truer than ever.