The UK began 2020 with a dispiriting hullaballoo about how the country should mark its departure from the European Union at 11pm on 31 January. Tabloids and politicians demanded that Big Ben should be rung, even though the bell and its tower are being restored and it would cost £500,000 to achieve. On BBC Newsnight, Jude Kelly, formerly the Southbank Centre’s artistic director, was a rare voice of reason, suggesting “respectful but muted” observance, given how much Brexit continues to divide the country.

The arts, however, are not divided: in a 2016 poll, 96% of members of the Creative Industries Federation said they wanted to remain in the EU; artists, museum directors and curators are widely, implacably opposed to Brexit, aware of the profound loss to our culture. So what would an artistic commemoration of this historic Brexit moment look like?

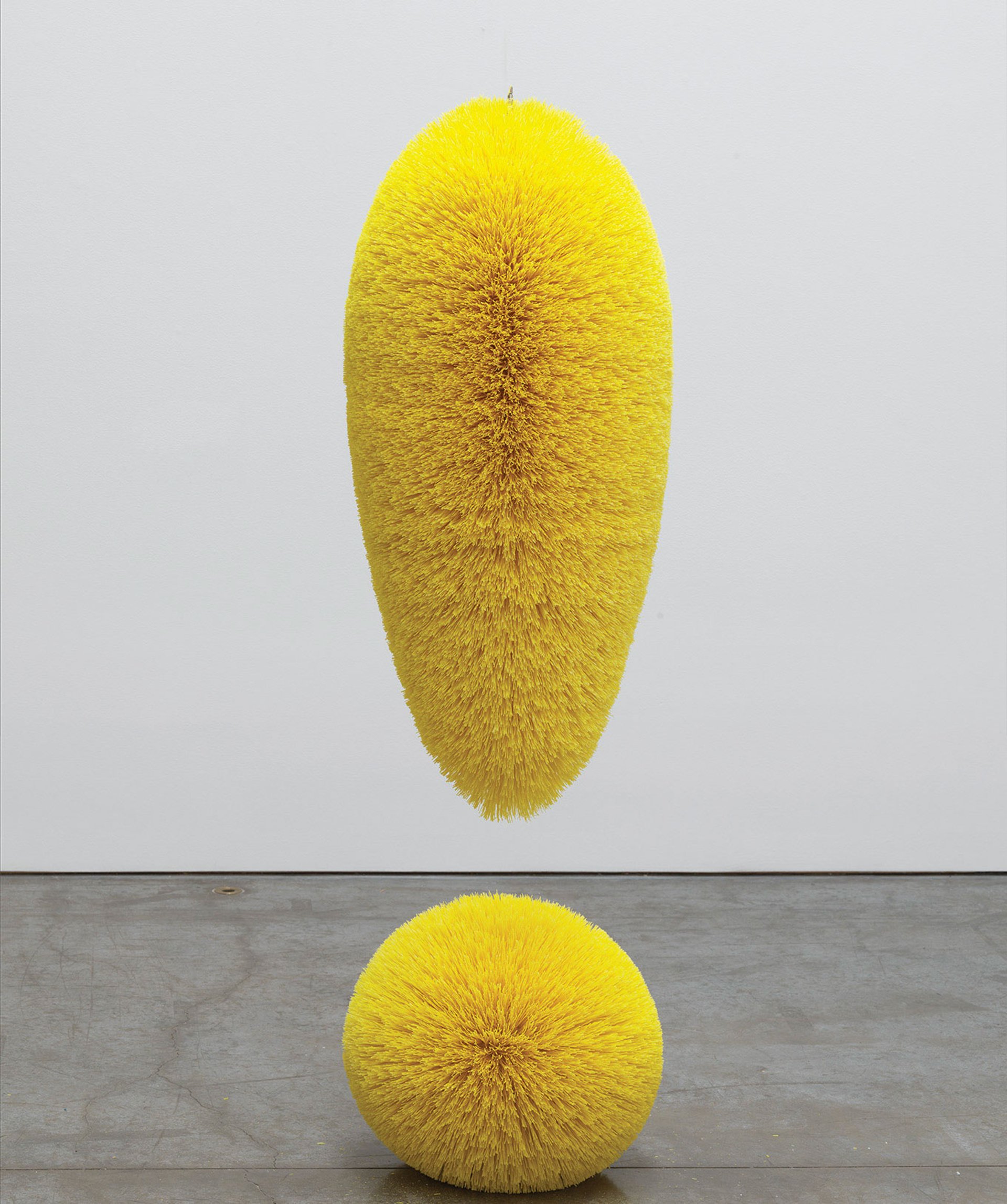

Richard Artschwager’s Exclamation Point (Yellow, 2001) is now on show at Gagosian in London © 2019 Richard Artschwager/Artists Rights Society (ARS); New York Photo: Rob McKeever; Courtesy Gagosian

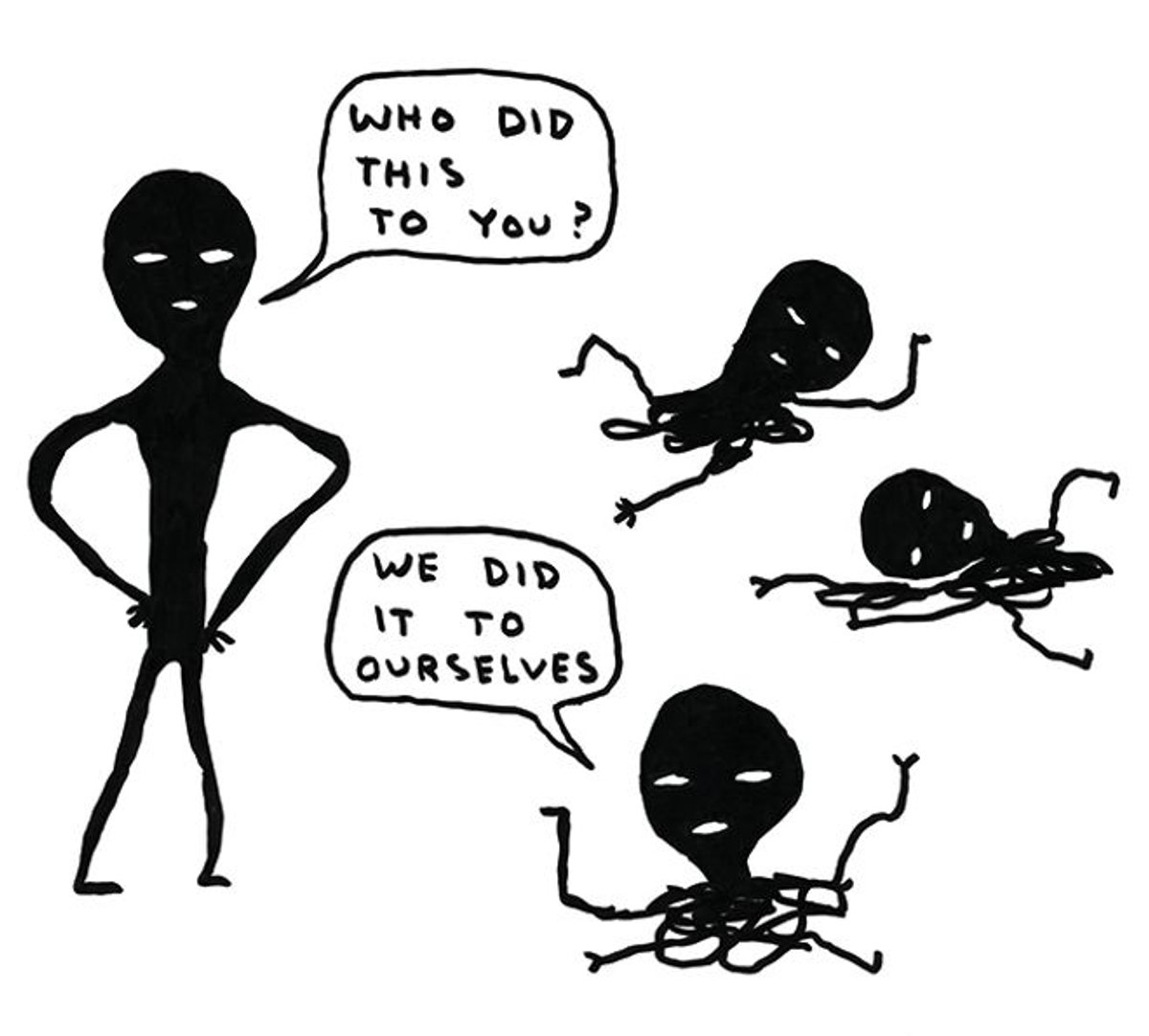

Humour seems an appropriate response. Last month, the curator Bob Monk suggested that Richard Artschwager’s giant exclamation mark in yellow plastic bristles, now at Gagosian in London, fits the bill. Arguably, London has already had a prominent sculpture that expressed the hysteria guiding Brexit and the Big Ben rumpus. David Shrigley’s elongated cartoonish thumbs-up in bronze, Really Good, commissioned in 2013, coincidentally appeared on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square only a few months after the referendum. In his statement, he wrote sardonically of his hope that the sculpture “would become a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy: if things are identified as being good, then therefore they become good and everything will get better.” It was written in the guise of “some hysterical political artist apparatchik”, yet could have been uttered by Boris Johnson and his fellow Brexiteers.

David Shrigley’s Really Good appeared on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square only a few months after the EU referendum

But while satire is tempting, melancholy and resignation have gripped many of us as Brexit looms. Those moods dominated a great recent example of public art: Susan Phillipsz’s Surround Me, in which the Scottish sound artist’s a cappella versions of Elizabethan and Jacobean madrigals and rounds echoed through London’s streets. Under London Bridge, the strains of Phillipsz singing John Dowland’s Flow, My Tears drifted with the lapping waves of the Thames.

So I think an apt response would be to meet sound with sound in Parliament Square: for them, the bell tolls; for me, that Elizabethan lament: “Flow, my tears, fall from your springs!/Exiled for ever, let me mourn.”