It is easy to think that a multi-million-dollar museum expansion is a once-in-a-lifetime thing. But just as the Museum of Modern Art was working towards its recent $450m grand reopening, high-net donors were being invited to fundraising dinners at five other major institutions in New York alone—the New Museum, the Whitney, the Frick, the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Metropolitan. Step outside of the city, at any given time, and the collective institutional fundraising effort becomes a dizzying national spectacle, with no rest in sight. A new initiative called the Arts Funders Forum, supported by the Knight Foundation and run by the strategic advisory firm M+D, launched in Miami Beach this week with the aim of identifying the current state of cultural philanthropy.

The forum was started in 2016, when then candidate Donald Trump promised to gut the National Endowment for the Arts. The NEA survived that particular campaign—and the US president’s continued calls for its defunding since taking office—but what would happen if next time it did not, the forum’s founders wondered? Would the private sector be able to fill the gap? Moreover, how can cultural institutions benefit from what is being billed as the largest ever transfer of wealth underway from the Baby Boomers to younger generations—estimated at anywhere between $30 trillion to $60 trillion according to analysts?

The first the organisers did was draw up a database of donors, directors, and other artworld insiders to get, as the forum’s director Melissa Cowley Wolf describes it, a 360-degree view of the sector. Of the more than 500 cultural professionals they surveyed, 78% said they were either “somewhat concerned” or “very concerned” about about philanthropic trends. A similar percentage said that the giving strategies for the next generation differed substantially from those of their predecessors. “Cultural institutions are struggling with an existential crisis to stay relevant,” the forum organisers say.

Charles Venable, the director of Newfields in Indiana (which encompasses the former Indianapolis Museum of Art, an art and nature park, and a botanical gardens), says that if museums live in a world of scarcity, it is, at least in part, their own doing. “We’ve been expanding at an enormous rate, certainly since the 1980s, adding square footage, and staff, and costs, and programming, at an increasingly fast pace, which largely contributes to this sense that we never have enough money.”

Beyond that, there is the cost of the art itself. A museum might have a decent operating endowment, but when it comes to acquisitions they are no match for private collectors. This in turn means that creating exhibitions has never been more expensive. As Dennis Scholl, the collector and president of Oolite Arts in Florida points out, the more valuable the art, the higher the costs associated with its care: “Shipping is insane, insurance is insane…” he says.

And then there is the shift in the nature of philanthropy. For the generations that lived through the Second World War and were born immediately after, the value of the art museum to the wider community was a given, and they donated funds, oftentimes unrestricted, accordingly. Now people take a more granular, strategic approach: they want to know exactly how their money will be used, and what impact it will have – with the data to prove it. Scholl calls them social venture capitalists.

Fred Bidwell, who is a trustee at the Cleveland Museum of Art, says donors are becoming more selective—and big museums will need to work harder to justify their costs. The new philanthropists want to collaborate with institutions, not just write cheques. And they prize innovation. He thinks institutions, in turn, need to lean into that entrepreneurial spirit. At the Indianapolis Museum of Art, it is precisely this approach that has seen Venable develop new donors, increase earned revenue (an income stream people don’t like to talk about) and pay off $42m of the museum’s debt (a common predicament people talk about even less). He has recently created a culinary arts department, and a pre-school, on the museum campus: extensive market research had shown him that his audience wants a social experience rather than an art historical education, and the more child-friendly and nature-conscious it is, the better.

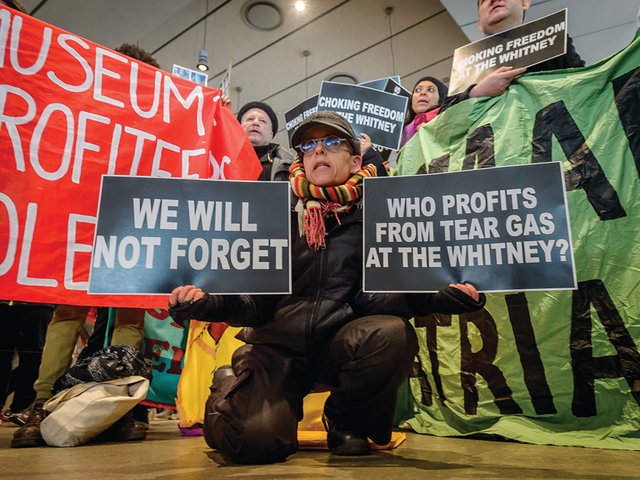

Ultimately, playing even a small role in helping an institution that serves the public to thrive is the bigger thrill for trustees like Dan Sallick, who serves on the board of Washington, DC’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. “We literally open the door of art to people from all over the world,” he says. And therein lies perhaps the greatest challenge for museums. At a time of heightened public scrutiny and increasing social justice concerns, people with money to give also come with their own missions. Convincing them and society at large that you do indeed serve the public, is paramount.