The celebrations of artists of the past have rarely acquired a political dimension, as has been the case with Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). One may recall that the legacy of this universal genius of the Renaissance was co-opted for a ruinous nationalistic agenda in the last century. From 9 May to 20 October 1939, a gargantuan exhibition on Leonardo in the Palazzo dell’Arte in Milan, commemorated the 17th anniversary of the fascist regime in Italy, organised on the orders of Benito Mussolini. Fortunately, we are in a different political moment in our understanding of Leonardo. On 2 May 2019, marking the 500th anniversary to the day of his death in Amboise, the presidents of Italy and France, Sergio Mattarella and Emmanuel Macron, appeared jointly to lay flowers at Leonardo’s “modern tomb” in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert within the precinct of the royal castle in Amboise. The geopolitical loan negotiations of paintings and drawings for the Musée du Louvre’s ambitious exhibition -- the culminating event of the Leonardo year of 2019 – have at times had their share of nationalistic drama.

Any serious international-loan exhibition on Leonardo is bound to present Herculean challenges, at the very least because of the variety and complexity of the master’s oeuvre, the mountains of literature on him to be digested, and the practical problems of securing what are enormously rare loans if the wish is to represent his most significant work. In bringing together 163 works (drawings, paintings, sculptures, and medals), the Louvre’s retrospective on Leonardo’s career is a once in a lifetime event. This is a beautiful, finely researched, and thoughtfully selected exhibition. It succeeds in telling the story of Leonardo’s artistic vision -- primarily as a painter -- with a freshness of insight and intellectual coherence that should please both the greater public and the scholar alike. The emphasis is on Leonardo’s “science de la peinture,” to quote the words of the curators Vincent Delieuvin and Louis Frank.

As one knows too well, Leonardo mostly defies categorisation

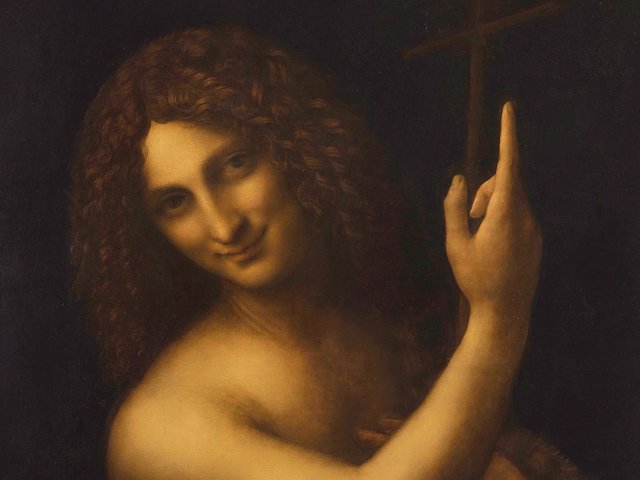

The loans anchor the four paintings by Leonardo from the Louvre’s permanent collection that are included in the exhibition: the Virgin of the Rocks of 1483-88; the portrait nicknamed La Belle Ferronnière of around 1495; the Saint John the Baptist begun around 1504-06; and the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne begun around 1507-08. The last is splendidly displayed with the cartoon of the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne from the National Gallery (London). The loans of securely autograph paintings by Leonardo include the Madonna Benois from the State Hermitage Museum (St Petersburg), the unfinished Saint Jerome (around 1480) from the Vatican Museums, The Musician from the Biblioteca Pinacoteca Ambrosiana (Milan), and the Scapigliata from the Galleria Nazionale (Parma). The ratio of the artist’s extant, securely autograph paintings to sheets with drawings and manuscripts is roughly 15 to 4,100. The great majority of Leonardo’s works in the Louvre exhibition, therefore, are drawings and manuscripts, with a particularly generous number of loans from the Royal Collection at Windsor. The Louvre itself owns around 30 drawings by Leonardo.

The arrangement of the works in the exhibition communicates a sense of Leonardo’s powerful artistic personality from beginning to end, and with arresting immediacy. The works are well paced within 13 rooms or compartments in the exhibition galleries, and the curators and the architect of the display have enhanced the aesthetic experience by creating vistas that unify sections from room to room. The paintings and drawings stand out with dramatic elegance on the walls painted in dark gray and lighter gray hues.

Léonard de Vinci, A study of a woman's hands (c.1490) Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Four large themes

The works in the show are grouped around four large, somewhat elastic themes: a mixture of the conceptual and the biographical on the artist, but which do not easily provide an umbrella for the actual works in each display. As one knows too well, Leonardo mostly defies categorisation. The first theme, “Shadow, Light, Relief”, is intended to describe the three major stylistic qualities of late 15th-century Florentine art, which especially characterised the training of Leonardo and other artists in their teacher Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop. The exhibition begins majestically with Verrocchio’s monumental bronze of The Doubting of Thomas, an exceptional loan from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello (Florence), sited at the centre of a semi-circular aedicula on whose walls hang the beautiful series of drapery studies on linen; they are mostly by Leonardo, but these attributions have led to much spilled ink in the literature. The curators then elaborate compellingly on the impact of 15th-century painting and sculpture on the young Leonardo, beyond his training and collaborations with Verrocchio, and to this effect they have enriched the displays with works from the Louvre’s own incomparable holdings of drawings, paintings, and sculptures.

The second theme, “Liberté” (a genial French take on the subject), is meant in a literal and conceptual sense. It covers the projects done by Leonardo at his moment of independence from Verrocchio, and also represents more abstractly the staggering creative freedom evident in Leonardo’s sketches on paper for early compositions, such as those for the Madonna of the Cat and the Uffizi Adoration of the Magi, as well as in his unfinished Vatican painting of Saint Jerome. For the first time in recent memory, Leonardo’s early Florentine-period drawings from the Musée Bonnat-Helleu (Bayonne) are seen in an international-loan exhibition outside their home institution, which is undergoing a renovation, and which are normally restricted by the “do not lend” policy imposed by Léon Bonnat’s bequest. The most famous Bayonne drawing depicts sketches of the hanging of Bernardo Baroncelli (following the Pazzi conspiracy), with notes about his costume.

A superb moment in the exhibition is the long room in which the Louvre’s Virgin of the Rocks and the Vatican Saint Jerome hang on the end walls, underscoring the short period of time intervening in their conception, and this is supported by the drawings on one of the long walls. On the opposite long wall, the fascinating juxtaposition of Antonello da Messina’s Portrait of a Man of around 1475 from the Louvre with Leonardo’s so-called Belle Ferronnière of around 1495 and the Ambrosiana Musician of around 1486-88, suggests the possibility of Antonello’s influence on Leonardo’s portraiture.

A large room is dedicated to “Science”, the third theme of the exhibition, and brings together Leonardo’s drawings and manuscripts relating to scientific subjects, including anatomy, geometry, architecture, mechanics and the flying machines, as well as the theory of painting. All of the master’s 14 manuscripts from the Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France (Paris) are displayed for the first time since 2003. The room also includes the Codex on the Flight of Birds from the Biblioteca Reale (Turin), two sheets of the Codex Leicester from the Collection of Bill and Melinda Gates, and the famous Vitruvian Man from the Gallerie dell’Accademia (Venice).

Léonard de Vinci, Étoile de Bethléem, Anémone des bois, Euphorbe Petite Éclaire Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The fourth theme of the exhibition, “Life” (Vie), again understood abstractly alludes to what elevated Leonardo’s approach to painting as a “divine science” in his maturity, based on his study of nature and science. It encompasses the works produced during the period of the master’s return to Florence around 1500, his three years in Rome, and final years in France. While the heavily conceptual quality of the four themes shaping the exhibition is probably confusing for the visitor who is actually walking through the exhibition (as there is not enough description on the text panels), the narrative threads of these themes, and related sub-themes, are more elegantly unified in the accompanying catalogue (albeit only in French).

Infrared images give a vivid sense of creative work in progress

An energetic campaign of scientific investigation of Leonardo’s paintings accompanied the planning of the Louvre exhibition, and an innovative and informative aspect of the show is the curators’ courageous decision to integrate the scientific imaging in infrared reflectography (IRR) of Leonardo’s paintings, which reveal the underdrawings and other early layers of design below the paint surface. The IRR images are presented backlit on glass screens on the walls, and are interspersed unobtrusively throughout the exhibition. These scientific images serve to remind the viewer of Leonardo’s paintings not present in the show, while at the same time communicating a vivid sense of Leonardo’s creative work in progress and his evolving thought over the long periods of time that he spent on his paintings. The image in IRR of the Mona Lisa (not in the show), a painting begun around 1503, can be compared to Leonardo’s damaged Portrait of Isabella d’Este cartoon, of two or so years earlier, which is an experimental drawing. The body scales of the female sitters are not only similar, but also the problems evident in Isabella’s pose, especially with her crudely foreshortened right arm and hand, appear gracefully resolved in the Mona Lisa’s pose. The IRR of the Mona Lisa also reveals a transformation of her slender body proportions (closer to a 15th-century ideal) into a monumental form as the master enlarged her mantle.

Installation view of Leonardo at the Louvre © Musée du Louvre/Antoine Mongodin

The inclusion of works by artists around Leonardo brings continuities of practices to the foreground. For instance, collaborative work was as true at the beginning of Leonardo’s career as it was in his maturity, and this, we may say, was partly the legacy of his training in Verrocchio’s bottega. The recent exhibitions on Verrocchio in the Palazzo Strozzi and Bargello in Florence, and in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, have helped underscore for us the climate of communal work that existed in Verrocchio’s extremely dynamic workshop. In Milan in the 1490s especially, Leonardo trained artists to emulate his style (hence, their nickname Leonardeschi), and some of these achieved a high degree of technical proficiency though woefully deprived of the master’s imagination and inventive powers. They replicated Leonardo’s figural tricks and the devices of chiaroscuro and sfumato, also collaborating with him in less important pictures: this is probably among the more difficult realities of Leonardo’s practices for us to absorb. In the exhibition, a wall with seven paintings of portraits and figures in bust-length allows the specialist viewer to recognise quite clearly -- probably for the first time, and beyond what the catalogue discusses -- the basic differences of style and technique of the two most important painters trained by Leonardo: Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono. The sensuously built-up, pictorially rich palette of Boltraffio contrasts to Marco’s very thin, enamel-like application of pigments, meticulously drawn forms, and nearly grayish green tonality of flesh areas. Somewhat aggressively looming over the displays in the large room of “Science” and the manuscripts is the enormous copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper painted by Marco d’Oggiono, from Ecouen, but softening the visual effect on a nearby wall are Boltraffio’s Strasbourg series of copies in pastel after the heads of the apostles and Christ from Leonardo’s Last Supper.

Any exhibition on Leonardo is probably bound to raise questions of attribution, particularly regarding paintings of modest scale from after 1500. As we know, Fra Pietro da Novellara wrote on 3 April 1501 to Isabella d’Este, lamenting that Leonardo “has done nothing else save for the fact that two apprentices are making copies, and from time to time, he lays his hand on them”. Hanging side by side in the exhibition, and not seen together since 1992, are the two best versions of the same composition of the Madonna of the Yarnwinder, respectively from an undisclosed European private collection and from the Collection of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry (Drumlanrig Castle). They clearly emanate from Leonardo’s workshop but are painted by two different artists: these two pictures may or may not have been retouched by the great master.

In contrast, the new imaging in IRR of the Scapigliata (Parma), performed by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure e Laboratori di Restauro of Firenze, has revealed an exquisite underdrawing, which proves definitively that this small painting on poplar wood (executed to look intentionally unfinished) is an autograph painting by Leonardo. It has all the hallmarks of his drawing style on paper -- superbly subtle modelling and contours that breathe with lively tonal inflections.

• Curators: Vincent Delieuvin and Louis Frank

• Leonardo da Vinci, Musée du Louvre, Paris 24 October 2019 – 24 February 2020