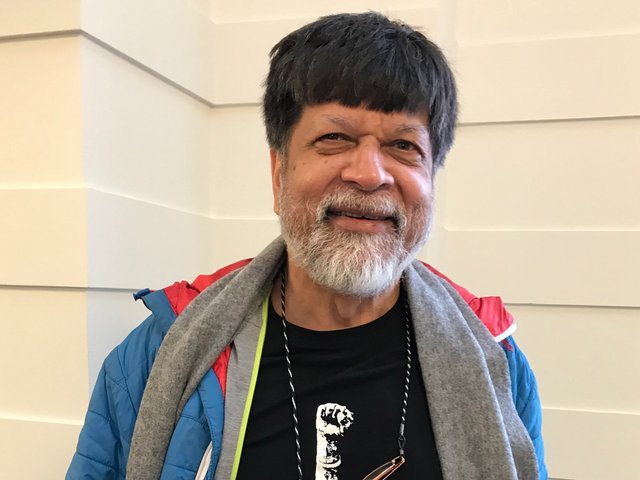

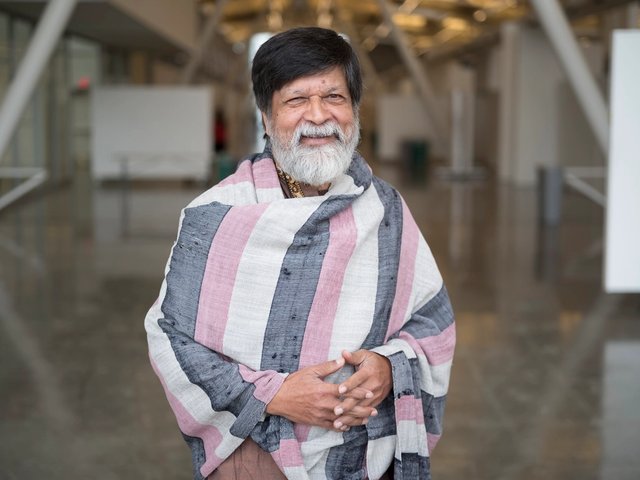

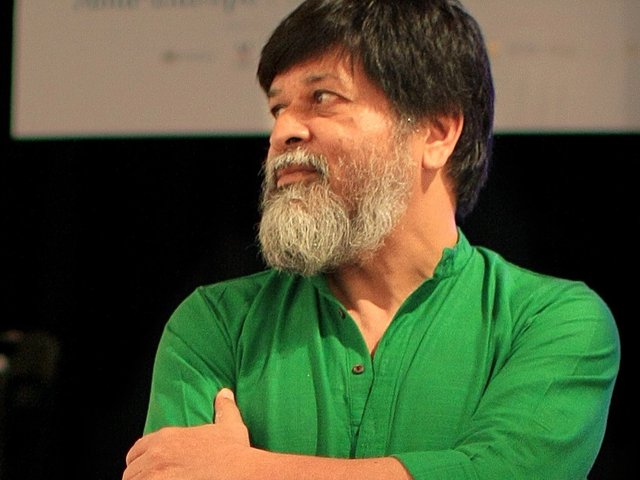

At 10:15pm, on 5 August 2018, Shahidul Alam’s neighbours heard him scream. Yet the plain-clothes policemen who lined the four flights of stairs to Alam’s flat in Dhaka, Bangladesh, remained completely silent. Waiting until Alam—a photojournalist, activist and educator—was alone, they disabled the CCTV in the building and cut the lights. Then they blindfolded, handcuffed and dragged Alam away to an unknown place, where he says they allegedly tortured him.

Alam remained in Dhaka’s Keraniganj prison until 20 November 2018, when the Bangladeshi high court finally granted him bail in the face of overwhelming international support for his safe release. The government has yet to drop the charges against him, which amount to propaganda against the state, on the basis of a televised Al Jazeera interview Alam gave the night before his arrest in support of student protests in Dhaka. Less than a year later, Alam’s four-decade-long photographic career—and his experiences of life in prison—are the focus of a major retrospective at New York’s Rubin Museum.

“What does a photographer do when his camera has been taken away?” Alam asks in the weeks leading up to the exhibition during a phone call from the UK, where he has been recovering with family. Unable to use the medium that has defined his career to reflect his experience of incarceration, he instead relied on his memory and the skills of his niece, Sofia Karim, a London-based architect turned artist, who co-ordinated the campaign to secure his release.

As the world turns

In addition to Alam’s images of the developing world, or the “majority world” as he prefers to describe how most of humanity lives, the Rubin exhibition features architectural and sculptural models, designed by Karim and based on Alam’s testimony, of the year he spent moving among the inmates of Dhaka. It includes tiny renderings of the sparrows Alam would feed his breakfast to each morning through the bars of his cell: “When you’re denied freedom, watching the birds fly through the bars of the cell and then out into the world became a powerful metaphor for me,” he says. Karim has captured the tessellated patterns the prisoners formed as they slept on the floor, squashed up against each other. She has constructed the elderly man serving a life-sentence, who was followed through the prison by a parade of feral cats.

“During my uncle’s incarceration, I constructed in my mind the spaces I imagined he occupied,” Karim says. “After his release, I built the models using his memories and my imagination. They show the hidden world of Keraniganj jail, a surreal netherworld of stories untold.”

The experience of prison took its toll on the 63-year-old Alam. He has needed medical treatment for an injury to his jaw sustained during his arrest, which stopped him from eating solid food for three months, and panic attacks have become part of his daily existence. Yet “there is sunshine in this dark story,” Alam says. He tutored inmates in how to paint and draw during impromptu workshops, which culminated in a large collaborative wall mural of one of Alam’s most iconic photographs, of fishermen heading out at dawn on the Brahmaputra river. The mural, he says, helped sustain him while he was imprisoned. With Karim’s help, he is now in the process of founding a prison library via book donations from supporters.

“My life has forever been altered,” Alam says of his time in prison. “Not being able to cycle, or go anywhere on my own, only travelling by car, not being able to stop and chat to strangers and having to constantly report to home base that I am safe makes my life so very different to the life I have so far led. The adjustment has been far from easy. There is now a new normal, which I have to accept.”

Rubin’s retrospective, defiantly titled Shahidul Alam: Truth to Power (8 November-4 May), shows that the campaigning artist has only become further committed to speaking out against injustice.