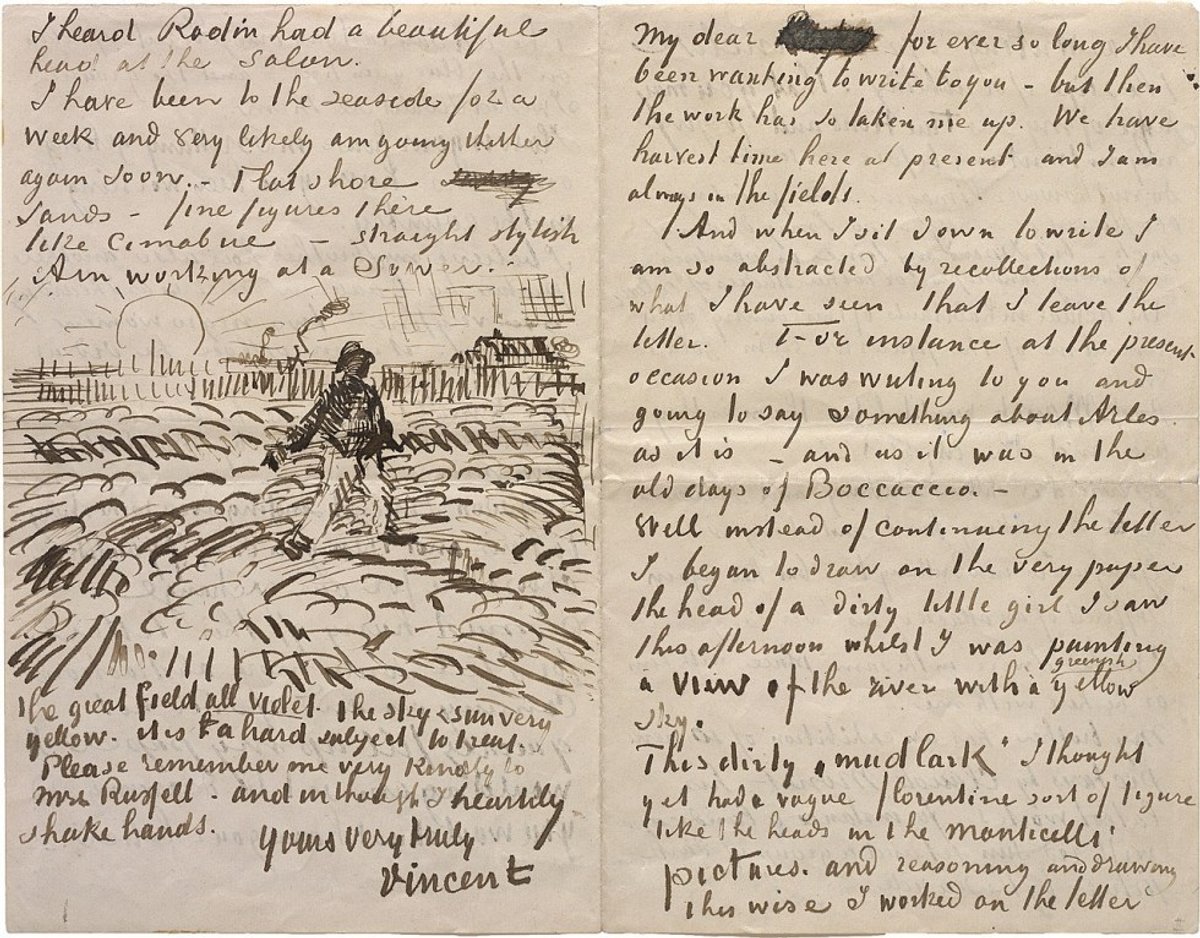

It is a decade, this month, since the publication of the annotated edition of Van Gogh’s 902 letters. In a 15-year project, the letters were painstakingly transcribed, translated into English and fully annotated. The result, published in October 2009, is a 6-volume, 2,164-page-edition and a searchable web version.

The statistics demonstrate the ambition of the Van Gogh letters project. Of the letters, 820 are from Vincent, with 658 to his brother Theo, and 83 to the artist (the vast majority are in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum). Altogether the text of the correspondence is 986,000 words. The letters are meticulously annotated, with another 160,000 words of notes in the printed edition (and 700,000 words in the longer web annotations). There are 4,300 illustrations.

The full edition has been published in four languages: English, French, Dutch and Chinese (with Korean now likely). Worldwide sales have now exceeded 15,000 copies, not bad for a publication which had a cover price of €395 (the English edition is currently out of print). A 780-page abridged version is available in eight languages. The freely available website has already had over 2.1m visitors.

Although there have been a series of earlier published editions of Van Gogh’s letters, the last major one was in the 1950s. The two original editors, Leo Jansen and Hans Luijten, began work on the letters project in 1994, and in 2002 they were joined by Nienke Bakker. We owe them an immense debt of gratitude. In the final year of production, a team of 20 worked on the project.

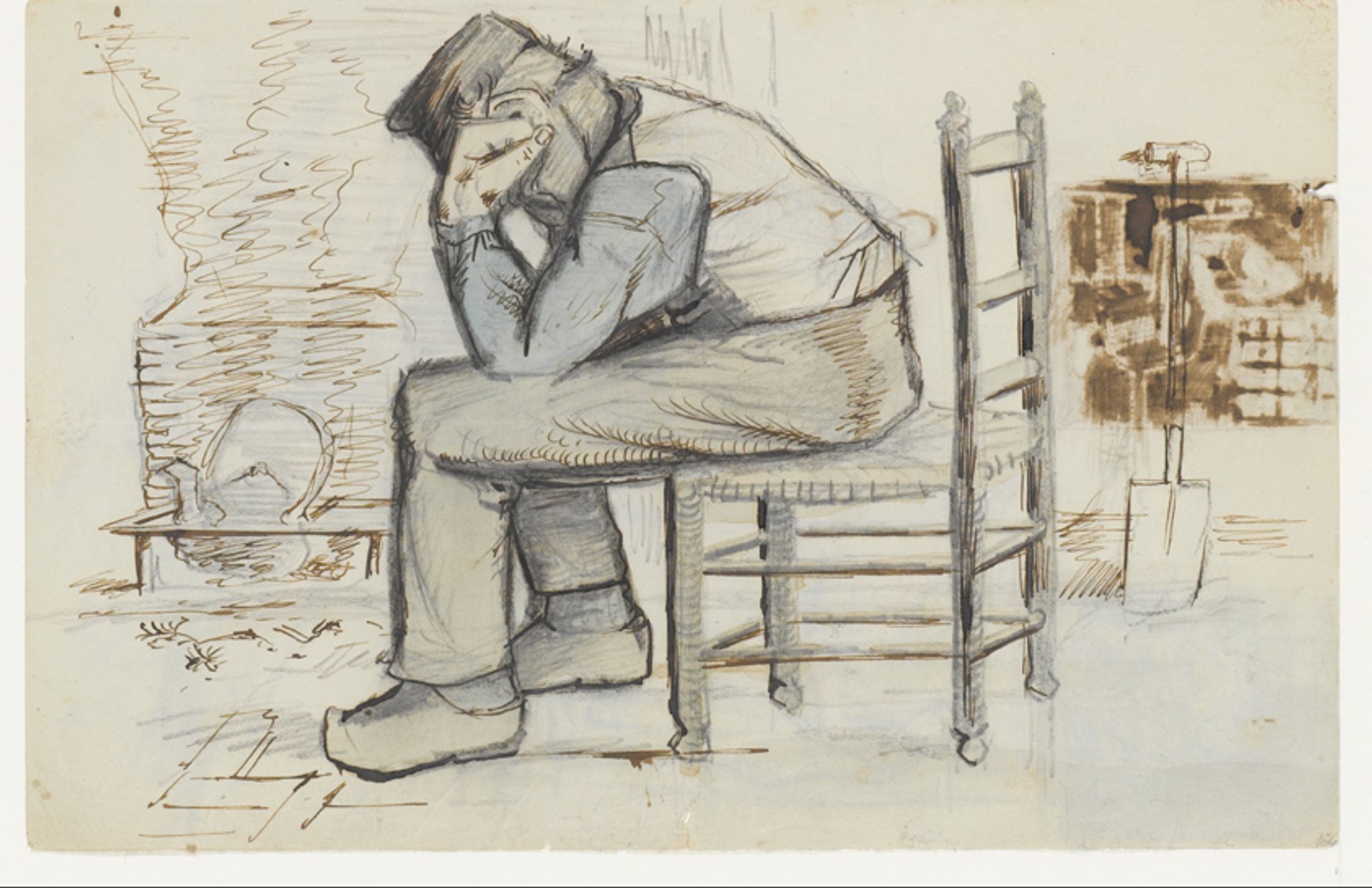

Sketch of the painting “Worn Out” in a letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo, mid September 1881, Etten (letter 172) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

If one wants to really read the letters, then the beautifully produced printed edition is ideal. For reference purposes the searchable web version is far better.

So what do we learn from the letters? The myth, perpetuated in the 1934 novel and subsequent 1956 film Lust for Life, is that Van Gogh was a highly-strung personality, slapping his paint onto canvas. But the letters tell a different story.

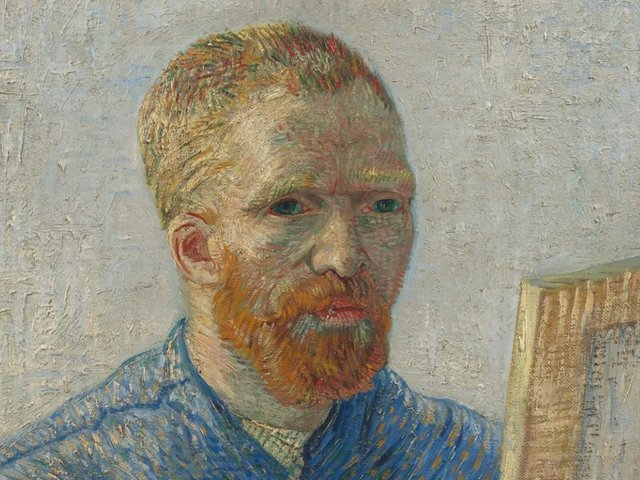

Bakker points out that the correspondence shows that Van Gogh was “not the isolated genius who created his works spontaneously and intuitively, but a well-connected, very methodical artist who set out on a path for himself, but also learned from others”.

The letters also emphasise that Van Gogh was well read. Some 800 literary sources, by 150 authors, have been identified in the annotations (the artist refers to Dickens in no fewer than 54 letters). He was talented at languages, writing fluently in French and reasonably in English, and he also read German.

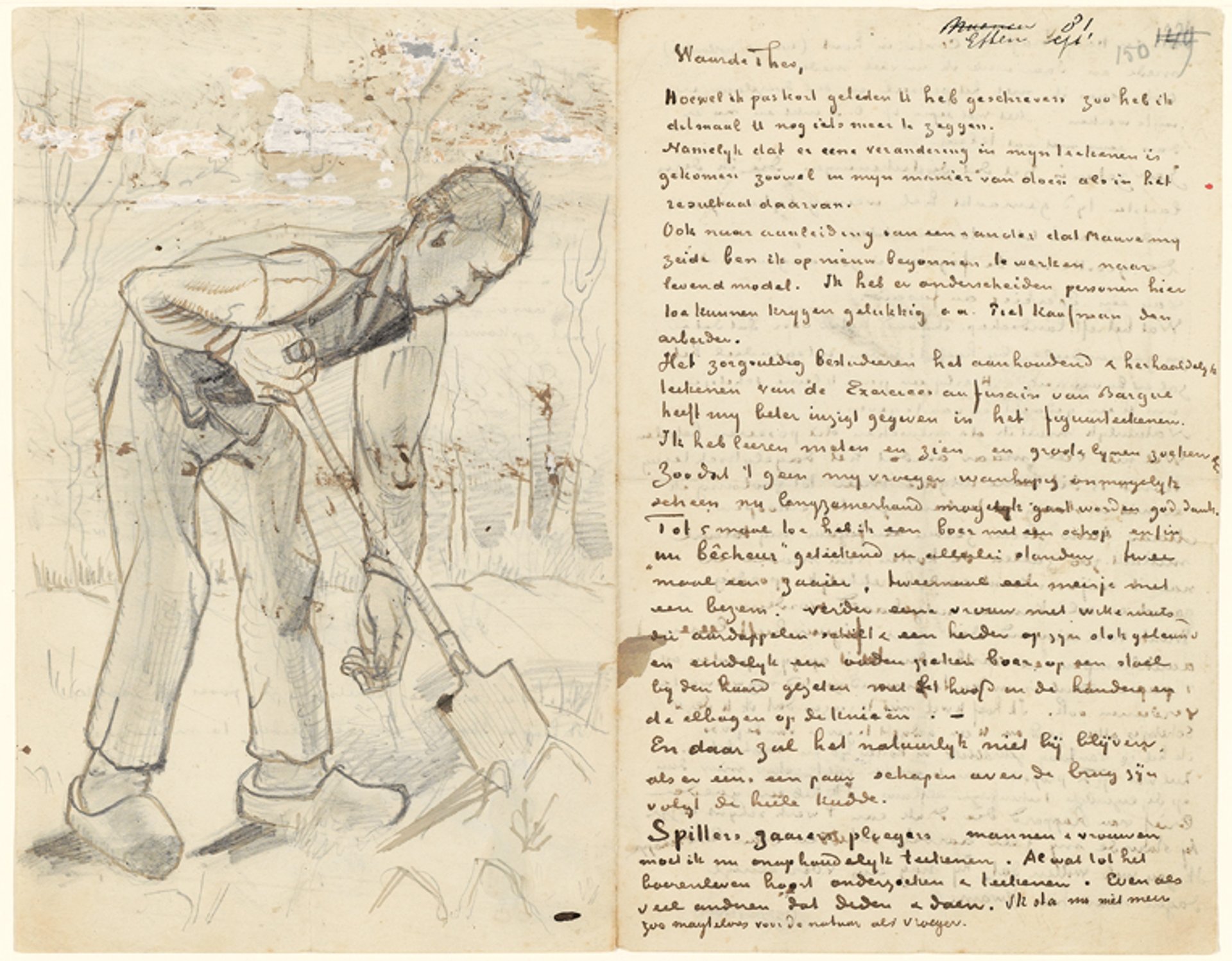

Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo, mid September 1881, with sketch of a Digger (letter 172) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation

Bakker, now the museum’s curator of Van Gogh paintings, says that having spent so many years analysing the correspondence, “you get to know the artist’s personality so well, his reasoning and his way of dealing with life—it’s all very human rather than the saint or genius that people like to see in him”.

Luijten’s work on the letters eventually led him to write a biography of Vincent’s sister-in-law, Jo Bonger, who did so much to preserve the artist’s legacy. His book, Everything for Vincent: the Life of Jo van Gogh-Bonger, was published in Dutch last month and will hopefully be translated into English next year.

Jansen now looks back and says that, for him, Van Gogh “became less of a madman and more of a human being”. After serving as a curator at the museum, he is now working on a similarly ambitious venture to publish the correspondence and writings of Piet Mondrian (under the auspices of the Netherlands Institute for Art History and the Huygens Institute for Dutch History).

Bakker concludes that Van Gogh was “not only a great artist, but also a talented writer who could put his thoughts on paper in a way that we can still relate to today”.

• An exhibition on Van Gogh’s Greatest Letters will be held at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 19 June-23 August 2020

• Earlier this week it was announced that Emilie Gordenker, currently director of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, will take over as general director of the Van Gogh Museum in February