Christie’s proclaimed its sale of the Jeremy Lancaster collection last night was “electric”.

It was not.

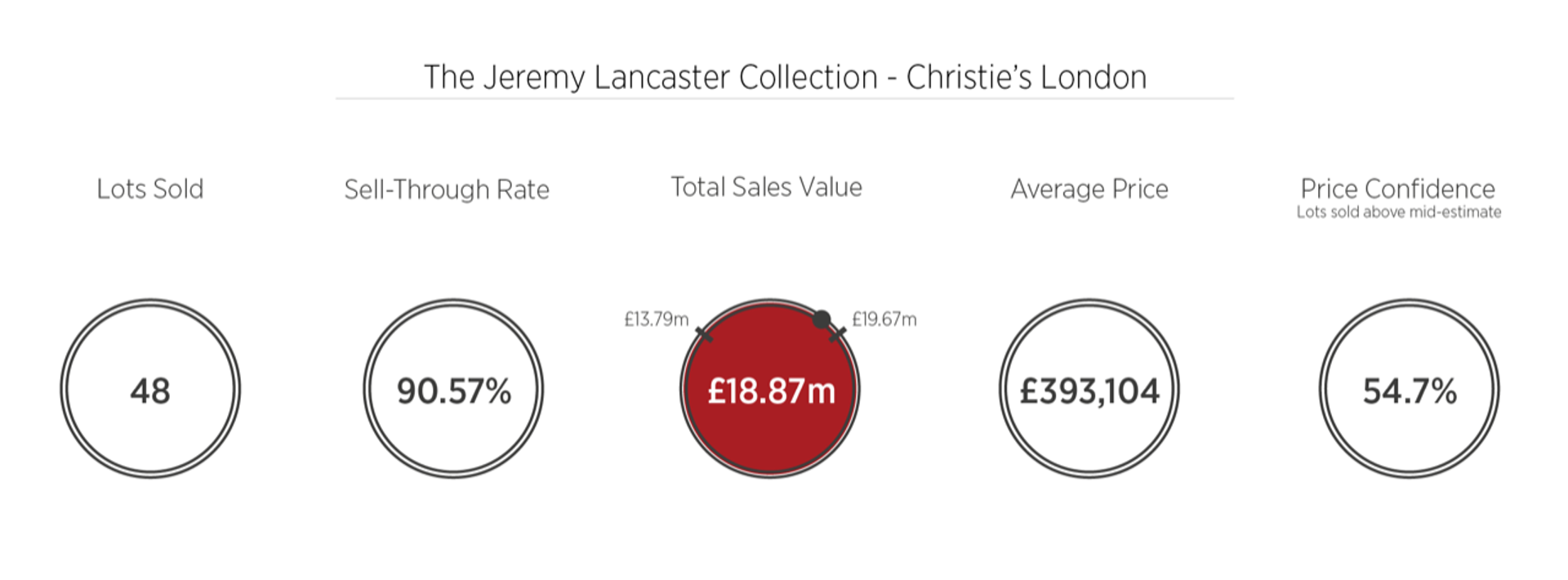

But it was healthy, buoyant, and, as the London-based dealer Pilar Ordovas says, it is probably "the most exciting sale of the week", achieving "strong results in what is otherwise, auction wise, a not so exciting week." It totalled £18.8m (£23m with fees), against a pre-sale estimate of £13.6m-£19.5m, with 91% of the 53 lots sold (one was withdrawn before the sale). Not bad for what Andre Zlattinger, Christie’s deputy chairman of post-war and contemporary art, describes as “a good old-fashioned collection of paintings for the home, to be lived with.”

With a taste for form and, above all, colour, the collection had been built by Lancaster, the British businessman who presided over the plumbing and heating company Wolseley, over 40 years. Lancaster was a thoughtful, modest collector, shunning the glitzy dinners and parties that characterise Frieze Week in London. He predominantly bought post-war British works with smatterings of American and European avant garde pieces, many bought through Leslie Waddington’s London gallery, occasionally at the expense of a family holiday and often taken home on the train from Paddington to Gloucestershire.

In 2016, the sale of Waddington’s own private collection also kicked off the Frieze Week auctions in the same sale-room. That actually was electric, but then the market was more buoyant and Waddington was lauded as a tastemaker—one who helped shape Lancaster’s tastes among others. Matthew Travers of the London gallery Piano Nobile says it was a "wonderful example of a collector having passion, excellent advice from dealers such as Leslie Waddington and a naturally good eye to put a collection together with such foresight" buying "works with impeccable, if not important provenance".

Data from the analysts ArtTactic shows that the average price in the Jeremy Lancaster collection was £393,104 Courtesy of ArtTactic

Unusually, no works were guaranteed, as Zlattinger says: “The family were not interested in guarantees, they just wanted to have an old-style auction. We had lots of approaches [from prospective third-party guarantors] as you can imagine.” Bidders from 26 countries registered and—allaying fears collectors from the region may be dropping away—30% of those bidders were from Asia. The final painting Lancaster bought, Andy Warhol’s silkscreen Clockwork Panda Drummer (1983), sold for £180,000 (£225,000 with fees) to an Asian buyer on the phone. Lancaster had purchased it at Sotheby’s in 2007 for £144,000 with fees, so not a huge mark up.

With consignments particularly thin for this week’s sales at all the auction houses—Brexit casting its long shadow once again—the Lancaster collection must be a blessed relief for the Christie’s team. The mix of post-war US names such as Philip Guston alongside Modern British artists like Howard Hodgkin and RB Kitaj, combined with the international crowd in town for Frieze, resulted in the unusual sight of David Zwirner bidding in the same sale as UK Modern British dealers such as Piano Nobile. While the former underbid on a Josef Albers’s Study for Homage to the Square: Red Tetrachord (1962), which sold on the phone for £1.3m (£1.6m with fees, estimate £600,000-£800,000) the latter underbid a Kenneth Martin abstract, which sold for £40,000 (£50,000 with fees).

"As a dealer specialising in the British field it is gratifying to see so many British artists competing in value with major international names," says Matthew Travers of Piano Nobile. The reason for the unsold lots, he thinks, "was less do do with their quality, than Christie's rather ambitious estimates which stalled the bidding. The works that looked like they could be a good buy often then went on to do better."

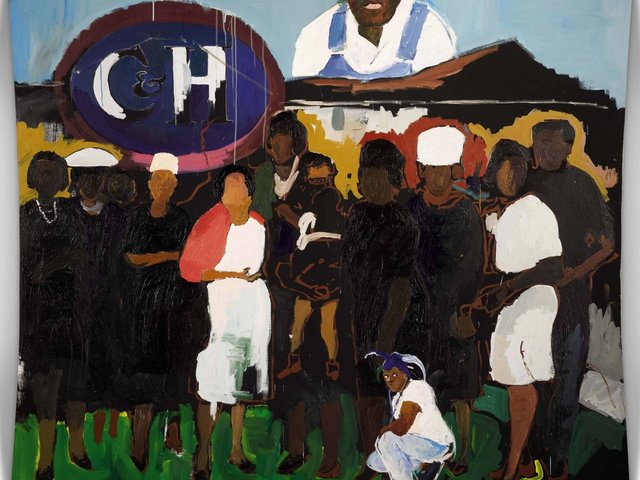

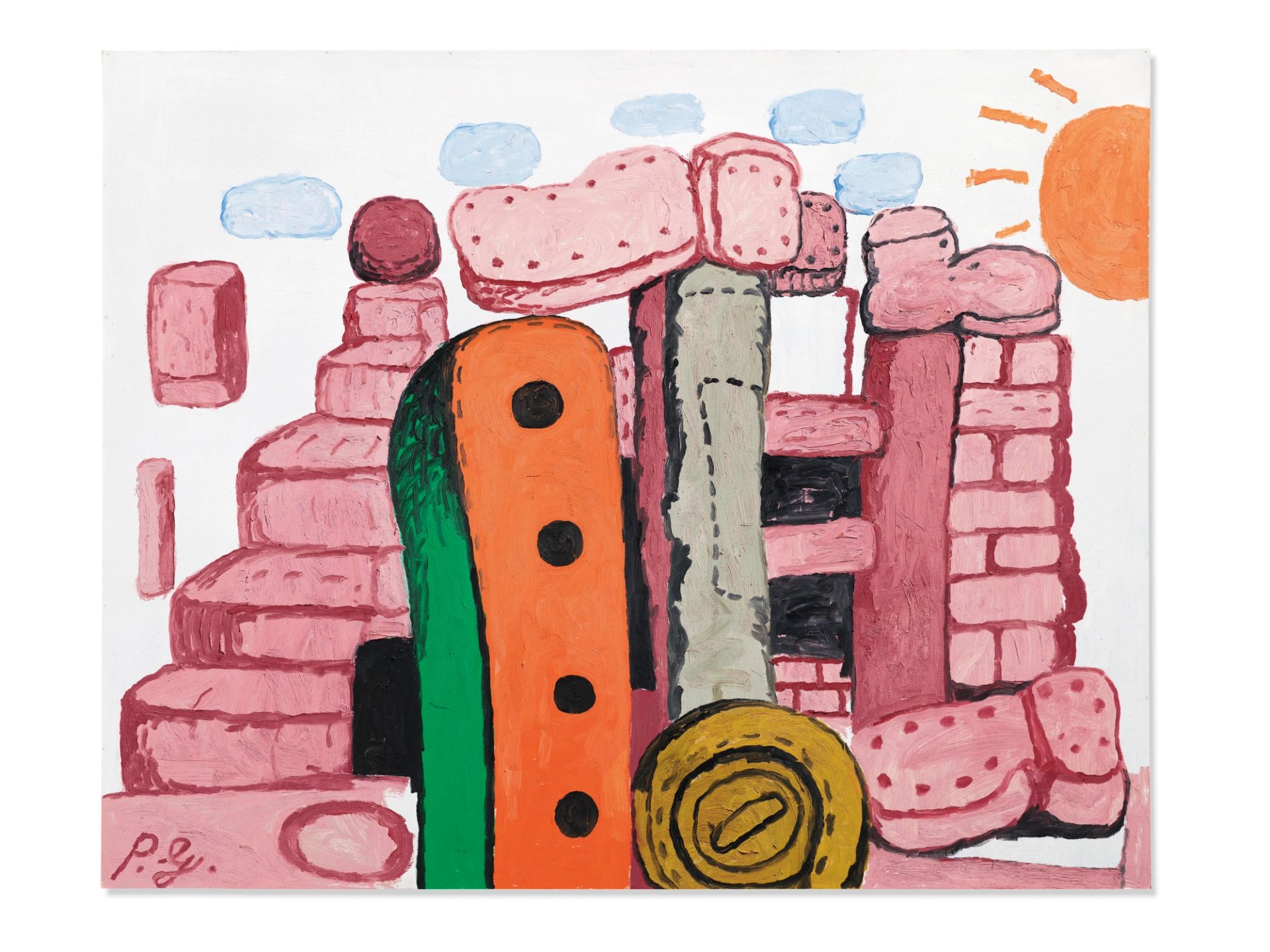

Philip Guston's Language I Courtesy of Christie's

There must not be many Philip Gustons hanging in rural Gloucestershire. And there are fewer now—here the top price was for the cover lot, Guston’s Language I (1973) sold for £3.2m (£3.8m with fees) above a £1.5m-£2m estimate. It was one of several paintings by the Canadian-born artist bought by Lancaster from Waddington during the 1980s and 90s. Guston’s star has risen rapidly in recent years—as Scott Reyburn points out, this painting was unsold at a Sotheby’s day sale in 1993 when estimated at $200,000-$250,000. Two years later, Lancaster bought it from Waddington. Another smaller Guston sold last night at £920,000 (£1.1m with fees) on the phone, underbid (as with the first Guston) by a woman in the room who, said the auctioneer Jussi Pyllkannen, “won’t let it go”. Except, in the end, she did.

There was a lot of trade bidding in the room, most of it underbidding but Simon Stock of Gagosian gallery picked up Frank Auerbach’s powerful Head of E.O.W. (1955) on behalf of a client for a mid-estimate of £1m (£1.2m with fees). “It was an exceptional work from a very special collection,” Stock says. “The new owner is extremely happy with this acquisition.”

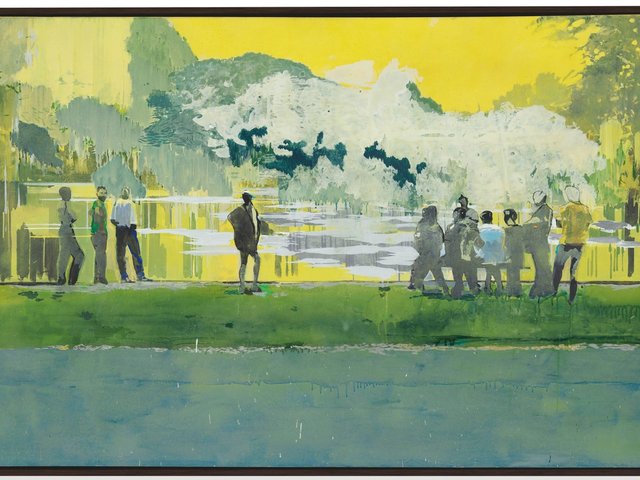

Howard Hodgkin painted Tea Party in America (1948) when he was just 16 Courtesy of Christie's

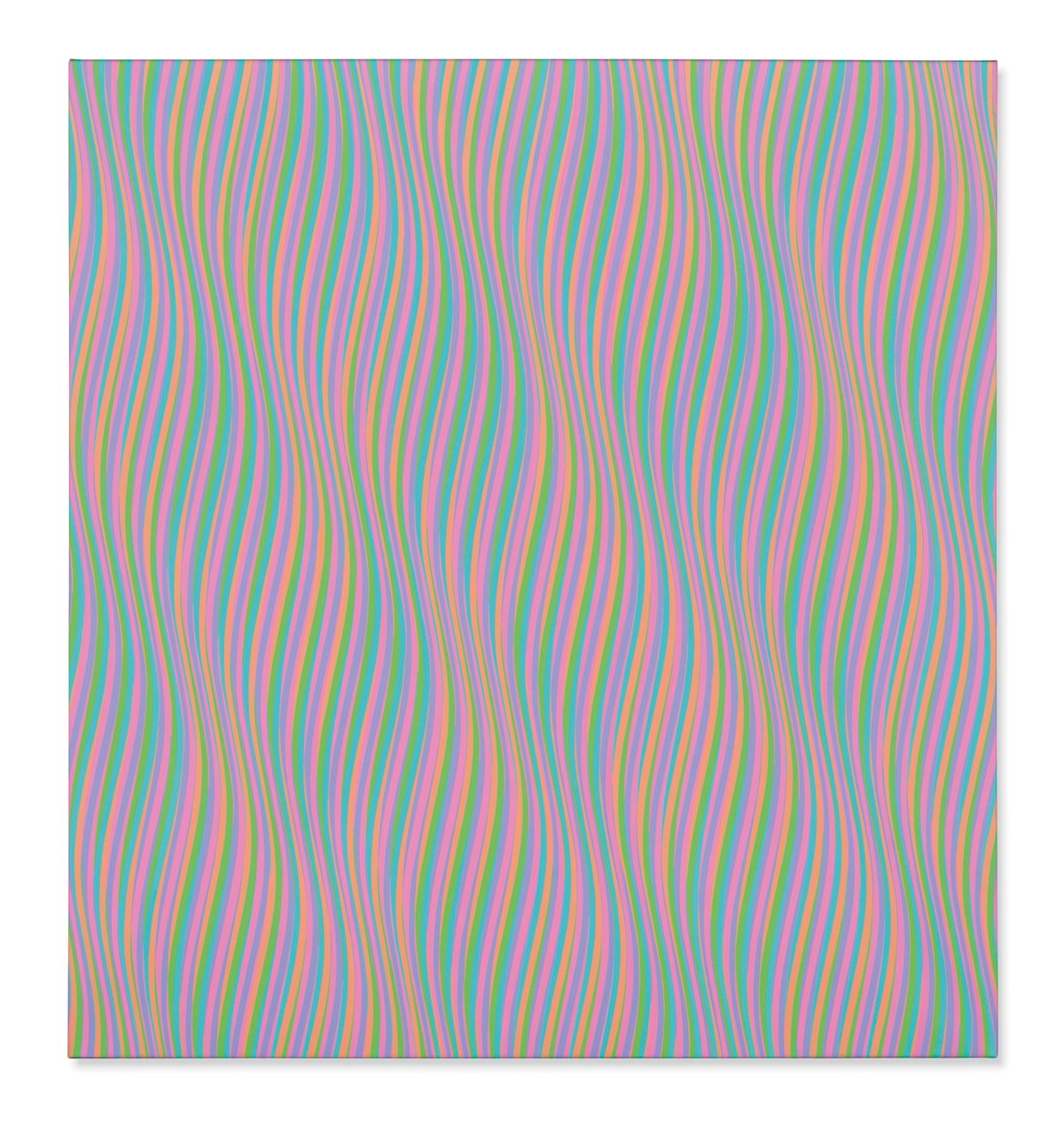

With a major Bridget Riley show opening at the Hayward Gallery on 23 October, there was strong interest in a couple of her paintings, particularly the rippling pastel-toned Orphean Elegy 7 (1979) from the end of the British painter’s lyrical period, which sold for £2.3m (£2.8m with fees) above a £1.5m-£2m estimate. Another smaller gouache, Study no.1 for Studio International Cover (1971) went for £250,000 (£311,250 with fees). “You can’t find Bridget Rileys and they were both great 1970s works,” Zlattinger says.

Lancaster particularly loved the work of another British painter, Howard Hodgkin, and the sale included works spanning seven decades of his career. Perhaps most intriguing, certainly the most esoteric, was an early figurative scene, Tea Party in America (1948), painted in gouache on cardboard when Hodgkin was just 16. Lancaster bought it at Sotheby’s in 1987 and it had been on long term loan to the Ashmolean in Oxford. It sold to Wenty Beaumont of the London advisory Wentworth Beaumont for £200,000 (£250,000 with fees) trouncing a £50,000-£70,000 estimate. A more typical, later abstract, the hot-red Lawson, Underwood & Sleep from 1977-80, sold on the phone for £500,000 (£611,250 with fees).

Naum Gabo's Linear Construction in Space No. 2 Courtesy of Christie's

Last, but not least, was Naum Gabo’s Linear Construction in Space No. 2, a unique Perspex and nylon monofilament sculpture from 1957-58, made when the Russian constructivist artist was living in New York. It was developed from Gabo’s designs for the larger of the two entrances of the Esso building in Rockefeller Plaza, commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller. This piece was given by the artist to Herbert Read in 1958 and Lancaster bought it in 1996 from Waddington. Thanks to strong interest the intricate, curvilinear piece—estimated at £150,000-£200,000—sold for £420,000 (£515,250 with fees) on the phone.