The German culture minister Monika Grütters has appointed a team of experts to draw up plans for a central institution charged with archiving and publicising the country’s photographic cultural heritage. “I cannot and will not stand idly by as the loss of valuable cultural heritage threatens,” she said at an event at Berlin’s Academy of Arts in July. “Is it not the job of the federal government to protect the work of important photographers, just as it does works of literature or music?”

Grütters said that her conversations with photographers and experts from museums, the art trade and academia have laid bare “a considerable backlog in securing the visual memory of our society”. She pointed out that neighbouring countries—the Netherlands, France, Austria and Switzerland—have set up national institutions to manage the legacies of leading photographers.

Preserving, cataloguing and digitising photographers’ work presents an enormous challenge, not only in terms of space requirements but also expertise, says Katrin Pietsch, a conservator at the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam and one of four members of Grütters’s expert team. The others are Thomas Weski of the Foundation for Photography and Media Art in Hanover, the curator and scholar Ute Eskildsen, and Thomas Gaehtgens, director emeritus of the Getty Research Institute.

“The dimensions of a photographer’s estate can be very large—you can quickly get to hundreds of thousands of negatives,” Pietsch says. “Museums often decline them.”

The Nederlands Fotomuseum collects, restores and exhibits Dutch photographic heritage. The Fotostiftung Schweiz, based in Winterthur, plays a similar role in Switzerland, safeguarding more than one million slides or negatives. It also mounts regular exhibitions.

“It’s not just a question of maintenance, but also of keeping legacies alive with exhibitions and research.”Inka Graeve Ingelmann, the head of photography and new media collections of the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich

In Germany, where culture policy is primarily the task of the 16 states, the management of photographic legacies has until now fallen to institutions including museums and university and state archives. But museums often lack resources, and collections can fail to find a home. Some photographers resort to setting up their own archives.

Still, Hubert Locher, the director of the German Documentation Centre for Art History in Marburg, is not convinced that a central repository is necessary. His organisation manages some photographers’ legacies, although its focus is more on photography used in art history than on the work of artists. Locher says he could imagine a network of photographic institutions, each with a specific focus, perhaps supported by a central federal office.

He notes that it is not always easy to distinguish fine art photographers from those who work in journalism or fashion. A photographer known for war reportage may also be featured in museum exhibitions. “Where do you draw the line?” Locher asks. “When is a photographer an artist?”

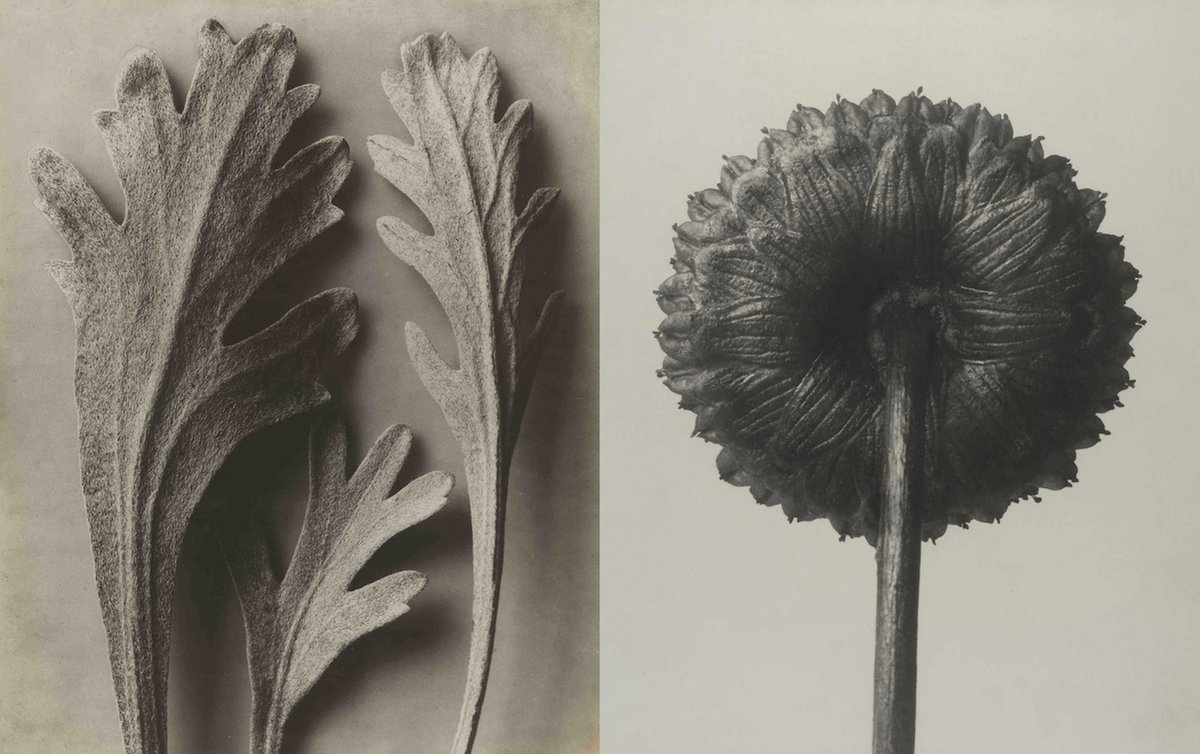

German museums such as the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich do occasionally accept individual photographic legacies, says Inka Graeve Ingelmann, the head of the photography and new media collections. The Pinakothek preserves the archives of Karl Blossfeldt and Albert Renger-Patzsch, comprising 2,400 and 3,500 original prints respectively. In addition, the two archives include around 11,000 glass-plate negatives, as well as numerous documents and rare books.

“But these are two of the most important photographers and very significant for German cultural heritage,” Graeve Ingelmann says. “You can’t do everything. It’s not just a question of maintenance, but also of keeping legacies alive with exhibitions and research.” Even a central body would have to be selective in the legacies it accepts, she warns.

Despite her misgivings, Graeve Ingelmann says she welcomes Grütters’s initiative. “A new central institution could play a significant role by setting an example and raising awareness of how important this issue is.”