The fourth edition of the Königsklasse exhibition, which opened in Bavaria in May (until 3 October), begins with Wolfgang Laib’s enormous pair of four-metre-high, 2,000kg beeswax ziggurats. Visitors lucky enough to make it to the show will realise the scale and ambition of Laib's work is needed, given the spectacular setting it must compete against.

Königsklasse is a series of exhibitions orchestrated by Corinna Thierolf, the chief curator of Munich’s Pinakothek der Moderne, that take place in the unfinished north wing of the Herrenchiemsee Palace, located on Herreninsel, an island on Chiemsee lake, 90km southeast of Munich.

Laib’s golden but fragmented monument is an apt metaphor for the palace itself. Built in the 19th century by the Bavarian monarch Ludwig II (best known for his fairytale Neuschwanstein Castle), Herrenchiemsee is a lavish tribute to Louis XIV’s Versailles.

So extravagant was Ludwig’s vision—the sumptuous hall of mirrors is longer than that of the French palace, while the finished sections of the house are stuffed full of the usual hotchpotch of Meissen, crystal, gilt and ormolu—that the entire palace had to be constructed in secret so as to avoid incensing the already overburdened Bavarian populace.

Only the main building of the palace was ever completed, but such was the expense that it brought the crown to the verge of bankruptcy before the king’s suspicious early death put a stop to work on the folly. In 1923, following the November Revolution, Crown Prince Rupprecht ceded Herrenchiemsee to the State of Bavaria.

Drawing on the collection of the Pinakothek, Museum Brandhorst and select private collections, Königsklasse IV revels in the juxtapositions it creates—most strikingly, perhaps, with the palace itself.

Here the bare-brick rooms of the unfinished north wing of the palace form the backdrop for tightly curated arrangement of paintings, sculptures and installations by artists such as Dan Flavin, Arnulf Rainer, On Kawara, Kazuo Shiraga and Laib, among others. A full room is dedicated to each artist, producing a highly concentrated presentation in which a key theme from each artist’s work is brought into relief by its proximity to the others.

This year’s edition, spanning two floors and incorporating ten rooms of the palace, begins with Laib’s aforementioned installation, Without Beginning and Without End. The installation comprises two monumental beeswax sculptures. The work’s massive scale, dull golden gleam and intoxicating aroma are an almost overwhelming sensory combination.

Indeed, the entire exhibition has been staged by Thierolf to eke out carefully constructed contrasts and intriguing parallels, an evolving dialogue between the ephemeral and the eternal, time and space, light and dark, weight and lightness.

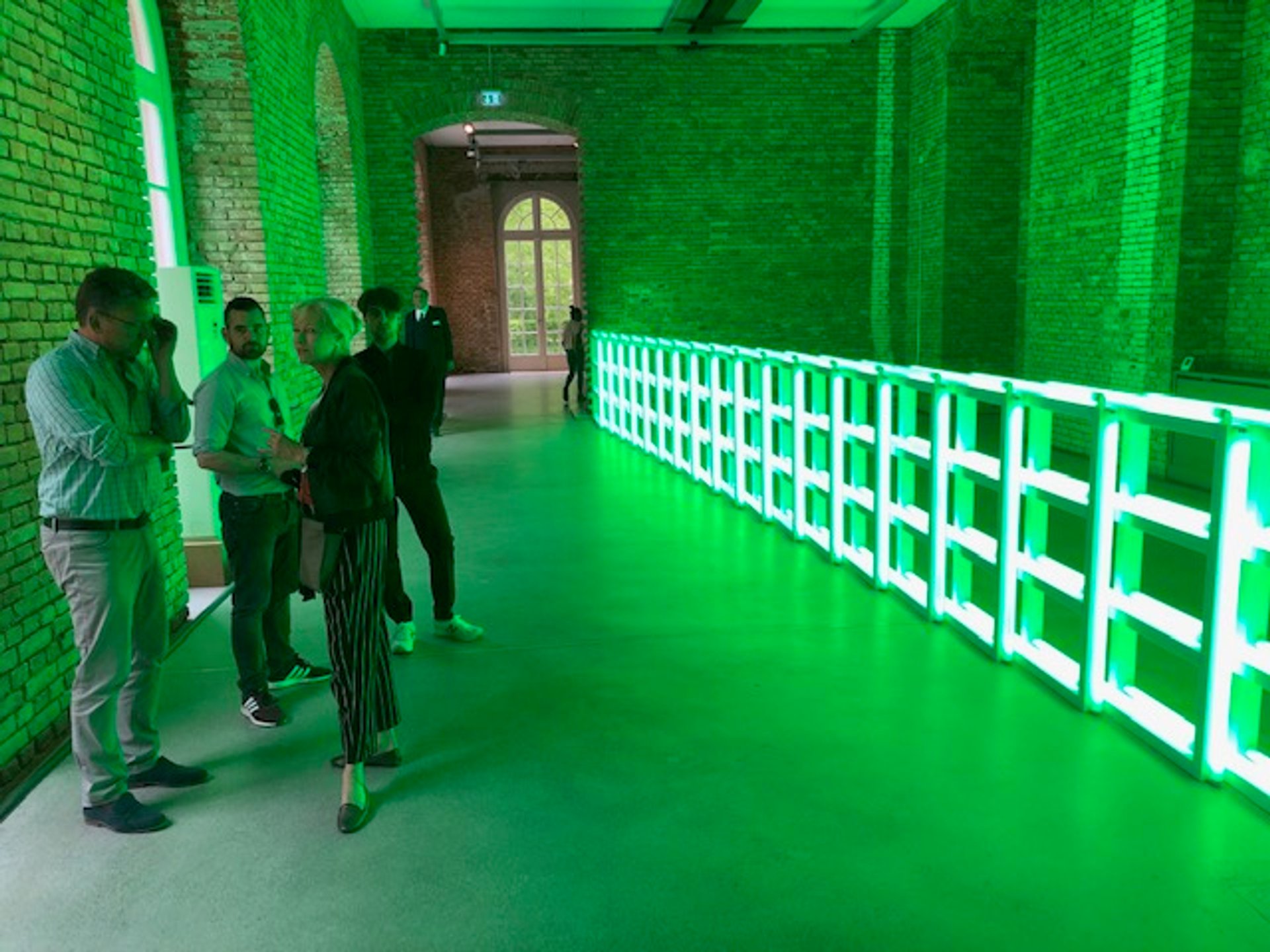

In a piece of careful juxtaposition, the room following Laib’s work features Arnulf Rainer’s 1969 Kreuz Schwarz. Here, the Austrian painter’s inverted pyramid, which has the curious effect of seeming to suck in the light, is presented with Laib’s golden monument still visible through the staggered brickwork of the entranceways to the previous room. In turn, Dan Flavin’s fluorescent Monuments that follow are used to produce what amounts to a sort of chiaroscuro effect in the comparison with Rainer’s dark crosses. And so it goes on.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to you, Heiner, with admiration and affection, 1973) © Estate of Dan Flavin / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019)

The jewel-like landscapes of Etel Adnan, in this setting seem to evoke the German tradition of seelenlandschaft (soulscape) painting, imagined landscapes that draw on memory and the past. While Thierolf describes them as, “monumental”, their diminutive size and precise delineation are a welcome relief from the occasionally bombastic offerings of some of the works they appear alongside.

The connections drawn between the work of Japanese artists On Kawara (1932-2014) and Kazuo Shiraga (1924-2008) are particularly instructive as both artists seek to encapsulate a precise moment in time. A total of eight of Kawara’s works, spanning six decades, are on loan in the exhibition. These paintings record, on canvas only, the date of their creation in a format unchanging over the decades, an exercise in constancy and control. By comparison, Shiraga’s works go off like bombs on the canvas, explosions of movement, colour and energy shaped by the artist’s writhing studies in spontaneity.

There are issues, however: the works by Shiraga are billed as the Gutai artist’s first museum show in Germany to date, and those who make the trip on that basis will be somewhat underwhelmed with the rather small selection on offer.

Nevertheless, the show represents an astute move by Thierolf and the Pinakothek der Moderne, allowing the curator to flex her muscles while also providing the museum with the opportunity to flatter collectors by including loaned works alongside pieces from the permanent collection of the museum. It is a move that will surely reap dividends for the Pinakothek in future as it seeks to expand its already world-class collections.

The imaginative curation and astonishing setting result in a show so striking that Ludwig himself would surely have approved.

Königsklasse is made in association with the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen and the Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung.